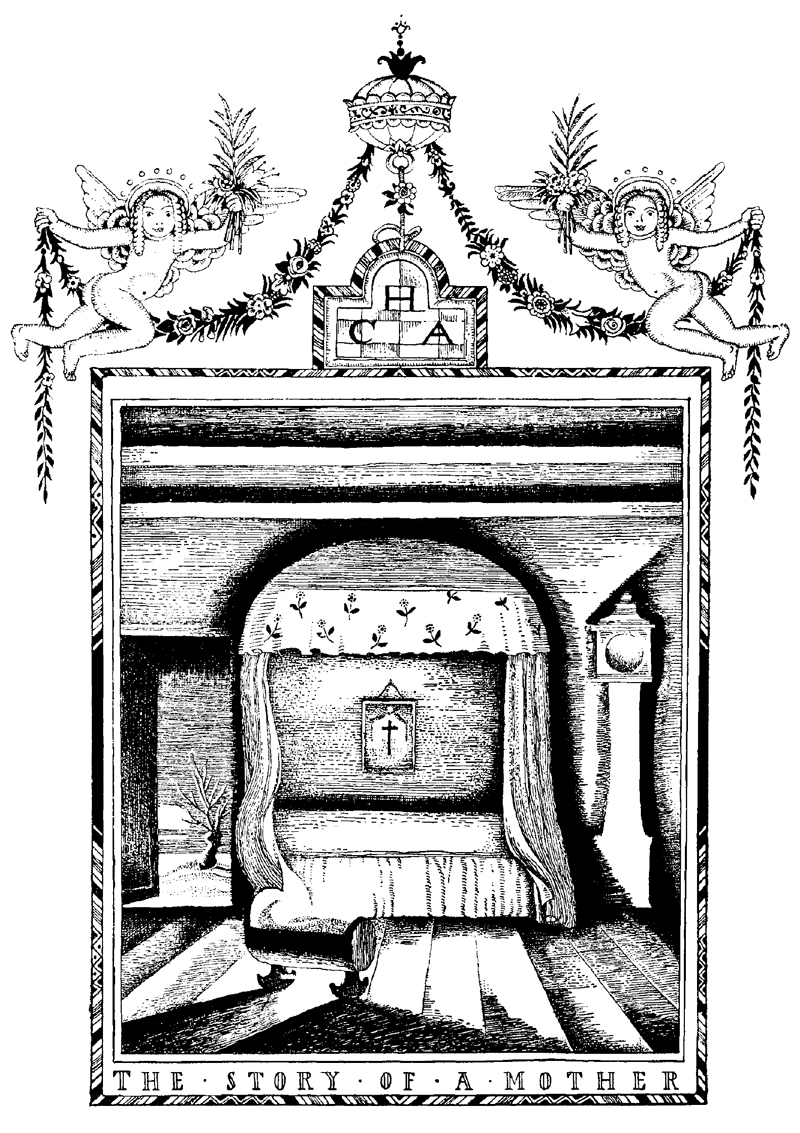

The Story of a Mother – A Hans Christian Andersen Tale

A sorrowful story of a mother chasing death, eyes that fall out and turn into pearls, and a garden of God’s flowers.

The Story of a Mother

– A Hans Christian Andersen Tale –

A MOTHER sat by her little child: she was very sorrowful, fearing that it would die. Its little face was pale, and its eyes were closed. The child drew its breath with difficulty, and sometimes as deeply as if it were sighing; and then the mother looked more sorrowfully than before on the little creature.

There was a knock at the door, and a poor old man came in, wrapped up in something that looked like a great horse-cloth, for that keeps one warm; and he needed it, for it was cold winter. Without, everything was covered with ice and snow, and the wild wind blew so sharply that it cut one’s face.

And as the old man trembled with cold, and the child was quiet for a moment, the mother went and put some beer on the stove in a little pot, to warm it for him. The old man sat down and rocked the cradle, and the mother seated herself on a chair by him, looked at her sick child that drew its breath so painfully, and lifted the little hand.

“You think I shall keep it, do you not?” she asked. “The good God will not take it from me!”

And the old man—he was Death—nodded in such a strange way, that it might just as well mean yes as no. And the mother cast down her eyes, and tears rolled down her cheeks. Her head became heavy: for three days and three nights she had not closed her eyes; and now she slept, but only for a minute; then she started up and shivered with cold.

The Story of a Mother Illustration by Kay Nielsen

“What is that?” she asked, and looked round on all sides; but the old man was gone, and her little child was gone; he had taken it with him. And there in the corner the old clock was humming and whirring; the heavy leaden weight ran down to the floor—plump!—and the clock stopped.

But the poor mother rushed out of the house crying for her child.

Out in the snow sat a woman in long black garments, and she said, “Death has been with you in your room; I saw him hasten away with your child: he strides faster than the wind, and never brings back what he has taken away.”

“Only tell me which way he has gone,” said the mother. “Tell me the way, and I will find him.”

“I know him,” said the woman in the black garments; “but before I tell you, you must sing me all the songs that you have sung to your child. I love those songs; I have heard them before. I am Night, and I saw your tears when you sang them.”

“I will sing them all, all!” said the mother. “But do not detain me, that I may overtake him, and find my child.”

But Night sat dumb and still. Then the mother wrung her hands, and sang and wept. And there were many songs, but yet more tears, and then Night said, “Go to the right into the dark fir wood; for I saw Death take that path with your little child.”

Deep into the forest there was a cross-road, and she did not know which way to take. There stood a thorn bush, with not a leaf nor a blossom upon it; for it was in the cold winter-time, and icicles hung from the twigs.

“Have you not seen Death go by, with my little child?”

“Yes,” replied the Bush, “but I shall not tell you which way he went unless you warm me in your bosom. I’m freezing to death here, I’m turning to ice.”

And she pressed the thorn bush to her bosom, quite close, that it might be well warmed. And the thorns pierced into her flesh, and her blood oozed out in great drops. But the thorn shot out fresh green leaves, and blossomed in the dark winter night: so warm is the heart of a sorrowing mother! And the thorn bush told her the way that she should go.

Then she came to a great lake, on which there were neither ships nor boat. The lake was not frozen enough to carry her, nor sufficiently open to allow her to wade through, and yet she must cross it if she was to find her child. Then she laid herself down to drink the lake; and that was impossible for any one to do. But the sorrowing mother thought that perhaps a miracle might be wrought.

“No, that can never succeed,” said the lake. “Let us rather see how we can agree. I’m fond of collecting pearls, and your eyes are the two clearest I have ever seen: if you will weep them out into me I will carry you over into the great greenhouse, where Death lives and cultivates flowers and trees; each of these is a human life.”

“Oh, what would I not give to get my child!” said the afflicted mother; and she wept yet more, and her eyes fell into the depths of the lake, and became two costly pearls. But the lake lifted her up, as if she sat in a swing, and was wafted to the opposite shore, where stood a wonderful house, miles in length. One could not tell if it was a mountain containing forests and caves, or a place that had been built. But the poor mother could not see it, for she had wept her eyes out.

“Where shall I find Death, who went away with my little child?” she asked.

“He has not arrived here yet,” said the old grave-woman, who was going about and watching the hothouse of Death. “How have you found your way here, and who helped you.”

“The good God has helped me,” she replied. “He is merciful, and you will be merciful too. Where shall I find my little child?”

“I do not know it,” said the old woman, “and you cannot see. Many flowers and trees have faded this night, and death will soon come and transplant them. You know very well that every human being has his tree of life, or his flower of life, just as each is arranged. They look like other plants, but their hearts beat. Children’s hearts can beat too. Go by that. Perhaps you may recognize the beating of your child’s heart. But what will you give me if I tell you what more you must do?”

“I have nothing more to give,” said the afflicted mother. “But I will go for you to the ends of the earth.”

“I have nothing for you to do there,” said the old woman, “but you can give me your long black hair. You must know yourself that it is beautiful, and it pleases me. You can take my white hair for it, and that is always something.”

“If you ask for nothing more,” said she, “I will give you that gladly.” And she gave her beautiful hair and received in exchange the old woman’s white hair.

The Story of a Mother Illustration by Kay Nielsen

And then they went into the great hothouse of death, where flowers and trees were growing marvellously together. There stood the fine hyacinths under glass bells, and there stood large, sturdy peonies; there grew water-plants, some quite fresh, others somewhat sickly; water-snakes were twining about them, and black crabs clung tightly to the stalks. There stood gallant palm trees, oaks, and plantains, and parsley and blooming thyme. Each tree and flower had its name; each was a human life: the people were still alive, one in China, another in Greenland, scattered about in the world. There were great trees thrust into little pots, so that they stood quite crowded, and were nearly bursting the pots; there was also many a little weakly flower in rich earth, with moss round about it, cared for and tended. But the sorrowful mother bent down over all the smallest plants, and heard the human heart beating in each, and out of the millions she recognized that of her child.

“That is it!” she cried, and stretched out her hands over a little blue crocus flower, which hung down quite sick and pale.

“Do not touch the flower,” said the old dame; “but place yourself here; and when Death comes—I expect him every minute—then don’t let him pull up the plant, but threaten him that you will do the same to the other plants; then he’ll be frightened. He has to account for them all; not one may be pulled up till he receives commission from Heaven.”

And all at once there was an icy cold rush through the hall, and the blind mother felt that death was arriving.

“How did you find your way hither?” said he. “How have you been able to come quicker than I?”

“I am a mother,” she answered.

And Death stretched out his long hands towards the little delicate flower; but she kept her hands tight about it, and held it fast; and yet she was full of anxious care lest she should touch one of the leaves. Then Death breathed upon her hands, and she felt that his breath was colder than the icy wind; and her hands sank down powerless.

“You can do nothing against me,” said Death.

“But the merciful God can,” she replied.

“I only do what He commands,” said Death. “I am His gardener. I take all His trees and flowers, and transplant them into the great Paradise gardens, in the unknown land. But how they will flourish there, and how it is there, I may not tell you.”

“Give me back my child,” said the mother; and she implored and wept. All at once she grasped two pretty flowers with her two hands, and called to Death, “I’ll tear off all your flowers, for I am in despair.”

“Do not touch them,” said Death. “You say you are so unhappy, and now you would make another mother just as unhappy!”

“Another mother?” said the poor woman; and she let the flowers go.

“There are your eyes for you,” said Death. “I have fished them up out of the lake; they gleamed up quite brightly. I did not know that they were yours. Take them back—they are clearer now than before—and then look down into the deep well close by. I will tell you the names of the two flowers you wanted to pull up, and you will see their whole future, their whole human life; you will see what you were about to frustrate and destroy.”

And she looked down into the well, and it was a happiness to see how one of them became a blessing to the world, how much joy and gladness was diffused around her. And the woman looked at the life of the other, and it was made up of care and poverty, misery and woe.

“Both are the will of God,” said Death.

The Story of a Mother Illustration by Kay Nielsen

“Which of them is the flower of misfortune, and which the blessed one?” she asked.

“That I may not tell you,” answered Death; “but this much you shall hear, that one of these two flowers is that of your child. It was the fate of your child that you saw—the future of your own child.”

Then the mother screamed aloud for terror.

“Which of them belongs to my child? Tell me that! Release the innocent child! Let my child free from all that misery! Rather carry it away! Carry it into God’s kingdom! Forget my tears, forget my entreaties, and all that I have done!”

“I do not understand you,” said Death. “Will you have your child back, or shall I carry it to that place that you know not?”

Then the mother wrung her hands, and fell on her knees, and prayed to the good God.

“Hear me not when I pray against Thy will, which is at all times the best! Hear me not! Hear me not!” And she let her head sink down on her bosom.

And Death went away with her child into the unknown land.

This story was taken from:

Shop the Tale

Discover this original tale, among many other macabre versions of your most beloved classics, in our collection of disturbingly dark fairy tales.

More stories from our Fairy Tale Library

Other Pook Press Books you might like…