The Snow Man

A diamond dusted garden, a know-it-all yard dog, and a stove-sick snowman.

The Snow Man befriends an old yard dog in a beautiful wintery garden where the trees look like a ‘forest of coral’. The Old Yard dog who has age and information, parts his wisdom about the sun and the moon, people and masters, and of course the stove with the flame tongue. It’s love at first sight for the Snow Man but it’s never going to end well.

This wintery classic from Hans Christian Andersen was originally published on 2 March 1861. It has been described as a lyrical and poignant complement to Andersen’s The Fir-Tree.

The Snow Man

A Hans Christian Andersen Tale

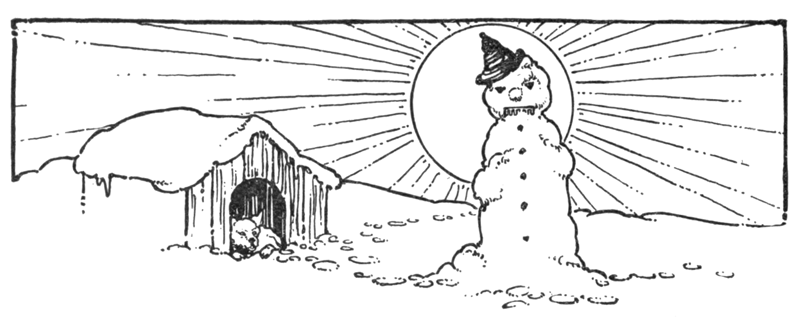

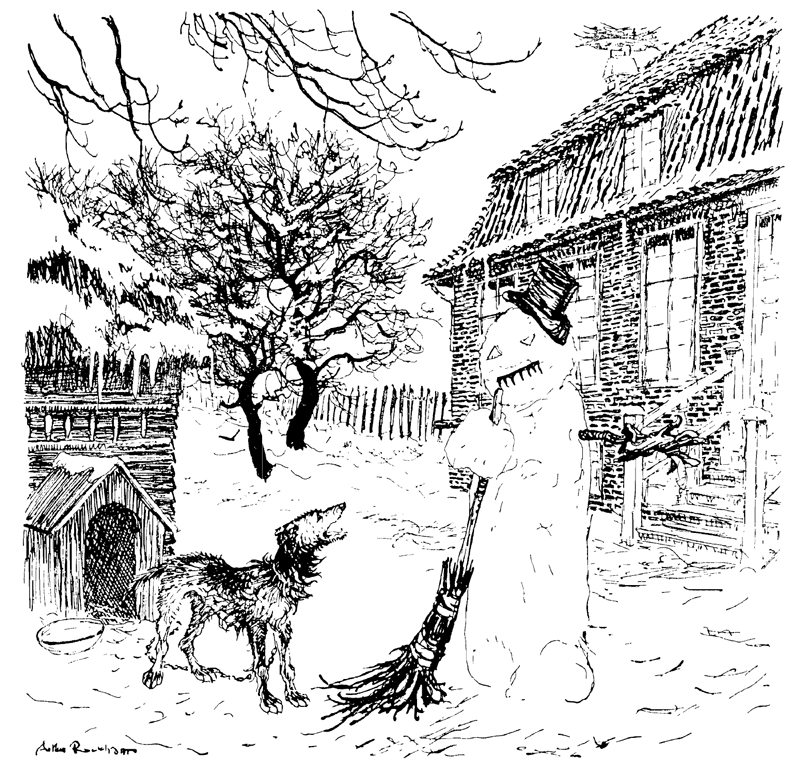

Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales – Vol II illustrated by Edna F. Hart

“IT’S so beautifully cold that my whole body crackles!” said the Snow Man. “This is a kind of wind that can blow life into one; and how the gleaming one up yonder is staring at me.” He meant the sun, which was just about to set. “It shall not make me wink—I shall manage to keep the pieces.”

He had two triangular pieces of tile in his head instead of eyes. His mouth was made of an old rake, and consequently was furnished with teeth.

He had been born amid the joyous shouts of the boys, and welcomed by the sound of sledge bells and the slashing of whips.

The sun went down, and the full moon rose, round, large, clear, and beautiful in the blue air.

“There it comes again from the other side,” said the Snow Man. He intended to say the sun is showing himself again. “Ah! I have cured him of staring. Now let him hang up there and shine, that I may see myself. If I only knew how I could manage to move from this place! I should like so much to move. If I could, I would slide along yonder on the ice, just as I see the boys slide; but I don’t know how to run.”

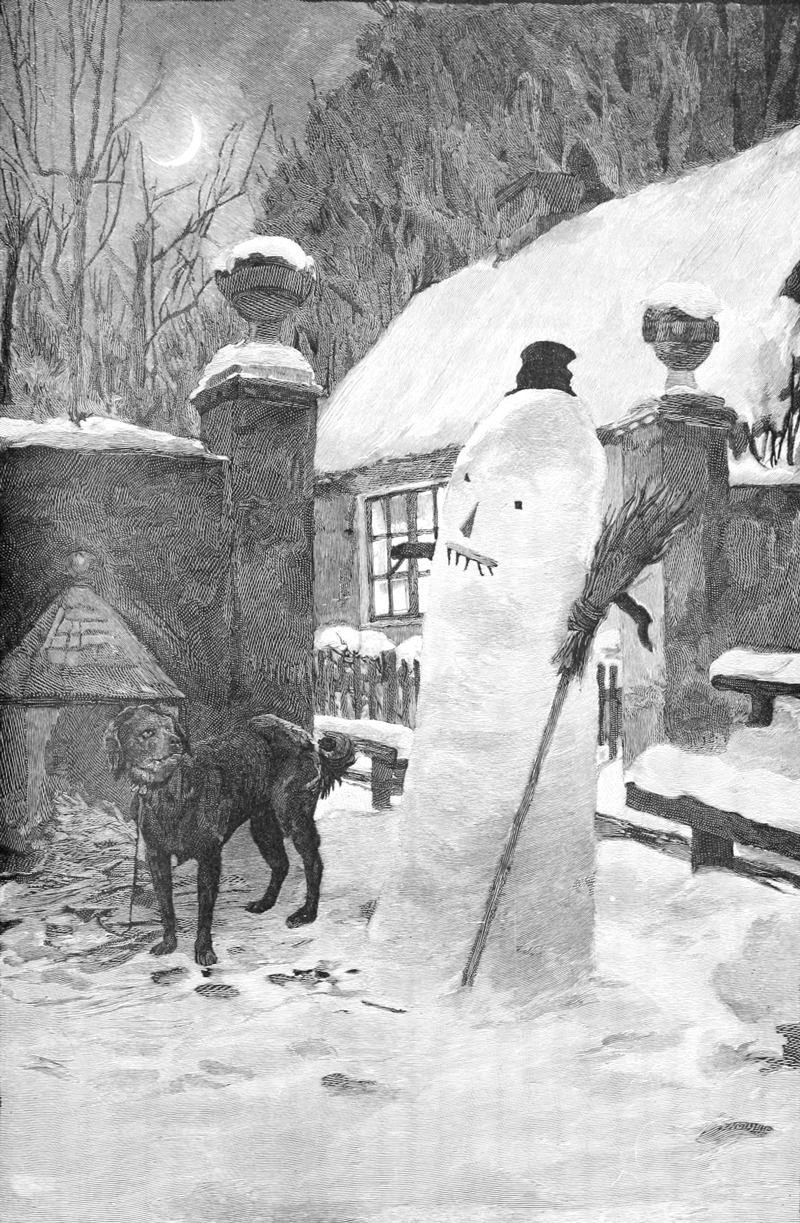

“Off! Off!” barked the old Yard Dog. He was somewhat hoarse. He had got the hoarseness from the time when he was an indoor dog, and lay by the fire. “The sun will teach you to run! I saw that last winter in your predecessor, and before that in his predecessor. Off! Off!—and they all go.”

“I don’t understand you, comrade,” said the Snow Man. “That thing up yonder is to teach me to run?” He meant the moon. “Yes, it was running itself, when I looked hard at it a little while ago, and now it comes creeping from the other side.”

“You know nothing at all,” retorted the Yard Dog. “But then you’ve only just been patched up. What you see yonder is the moon, and the one that went before was the sun. It will come again to-morrow, and will teach you to run down into the ditch by the wall. We shall soon have a change of weather; I can feel that in my left hind leg, for it pricks and pains me: the weather is going to change.”

“I don’t understand him,” said the Snow Man; “but I have a feeling that he’s talking about something disagreeable. The one who stared so just now, and whom he called the sun, is not my friend. I can feel that.”

“Off! Off!” barked the Yard Dog; and he turned round three times, and then crept into his kennel to sleep.

The weather really changed. Towards morning, a thick damp fog lay over the whole region; later there came a wind, an icy wind. The cold seemed quite to seize upon one; but when the sun rose, what splendour! Trees and bushes were covered with hoar-frost, and looked like a complete forest of coral, and every twig seemed covered with gleaming white buds. The many delicate ramifications, concealed in summer by the wreath of leaves, now made their appearance: it seemed like a lace work, gleaming white. A snowy radiance sprang from every twig. The birch waved in the wind—it had life, like the trees in summer. It was wonderfully beautiful. And when the sun shone, how it all gleamed and sparkled, as if diamond dust had been strewn everywhere, and big diamonds had been dropped on the snowy carpet of the earth; or one could imagine that countless little lights were gleaming, whiter than even the snow itself.

“That is wonderfully beautiful,” said a young girl, who came with a young man into the garden. They both stood still near the Snow Man, and contemplated the glittering trees. “Summer cannot show a more beautiful sight,” said she; and her eyes sparkled.

“And we can’t have such a fellow as this in summertime,” replied the young man, and he pointed to the Snow Man. “He is capital.”

The girl laughed, nodded at the Snow Man, and then danced away over the snow with her friend—over the snow that cracked and crackled under her tread as if she were walking on starch.

“Who were those two?” the Snow Man inquired of the Yard Dog. “You’ve been longer in the yard than I. Do you know them?”

“Of course I know them,” replied the Yard Dog. “She has stroked me, and he has thrown me a meat bone. I don’t bite those two.”

“But what are they?” asked the Snow Man.

“Lovers!” replied the Yard Dog. “They will go to live in the same kennel, and gnaw at the same bone. Off! Off!”

“Are they of as much consequence as you and I?” asked the Snow Man.

“Why, they belong to the master,” retorted the Yard Dog. “People certainly know very little who were only born yesterday. I can see that in you. I have age and information. I know every one here in the house, and I know a time when I did not lie out here in the cold, fastened to a chain. Off! Off!”

“The cold is charming,” said the Snow Man. “Tell me, tell me.—But you must not clank with your chain, for it jars within me when you do that.”

“Off! Off!” barked the Yard Dog. “They told me I was a pretty little fellow: then I used to lie in a chair covered with velvet, up in master’s house, and sit in the lap of the mistress of all. They used to kiss my nose, and wipe my paws with an embroidered handkerchief. I was called ‘Ami—dear Ami—sweet Ami.’ But afterwards I grew too big for them, and they gave me away to the housekeeper. So I came to live in the basement storey. You can look into that from where you are standing, and you can see into the room where I was master; for I was master at the housekeeper’s. It was certainly a smaller place than upstairs, but I was more comfortable, and was not continually taken hold of and pulled about by children as I had been. I received just as good food as ever, and much more. I had my own cushion, and there was a stove, the finest thing in the world at this season. I went under the stove, and could lie down quite beneath it. Ah! I still dream of that stove. Off! Off!”

“Does a stove look so beautiful?” asked the Snow Man. “Is it at all like me?”

“It’s just the reverse of you. It’s as black as a crow, and has a long neck and a brazen drum. It eats firewood, so that the fire spurts out of its mouth. One must keep at its side, or under it, and there one is very comfortable. You can see it through the window from where you stand.”

And the Snow Man looked and saw a bright polished thing with a brazen drum, and the fire gleamed from the lower part of it. The Snow Man felt quite strangely: an odd emotion came over him, he knew not what it meant, and could not account for it; but all people who are not snowy men know the feeling.

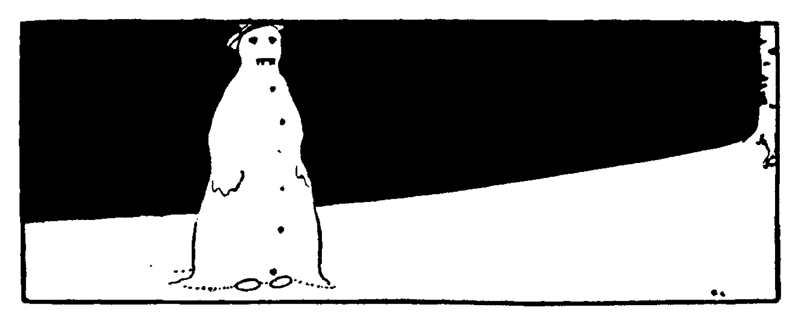

Fairy Tales and Stories by Hans Christian Andersen illustrated by Hans Tegner

“And why did you leave her?” asked the Snow Man, for it seemed to him that the stove must be of the female sex. “How could you quit such a comfortable place?”

“I was obliged,” replied the Yard Dog. “They turned me out of doors, and chained me up here. I had bitten the youngest young master in the leg, because he kicked away the bone I was gnawing. ‘Bone for bone,’ I thought. They took that very much amiss, and from that time I have been fastened to a chain and have lost my voice. Don’t you hear how hoarse I am? Off! Off! that was the end of the affair.”

But the Snow Man was no longer listening to him. He was looking in at the housekeeper’s basement lodging, into the room where the stove stood on its four iron legs, just the same size as the Snow Man himself.

“What a strange crackling within me!” he said. “Shall I ever get in there? It is an innocent wish, and our innocent wishes are certain to be fulfilled. It is my highest wish, my only wish, and it would be almost an injustice if it were not satisfied. I must go in there and lean against her, even if I have to break through the window.”

“You will never get in there,” said the Yard Dog; “and if you approach the stove then you are off! off!”

“I am as good as gone,” replied the Snow Man. “I think I am breaking up.”

The whole day the Snow Man stood looking in through the window. In the twilight hour the room became still more inviting: from the stove came a mild gleam, not like the sun nor like the moon; no, it was only as the stove can glow when he has something to eat. When the room door opened, the flame started out of his mouth; this was a habit the stove had. The flame fell distinctly on the white face of the Snow Man, and gleamed red upon his bosom.

“I can endure it no longer,” said he; “how beautiful it looks when it stretches out its tongue!”

The night was long; but it did not appear long to the Snow Man, who stood there lost in his own charming reflections, crackling with the cold.

In the morning the window-panes of the basement lodging were covered with ice. They bore the most beautiful ice-flowers that any snow man could desire; but they concealed the stove. The window-panes would not thaw; he could not see her. It crackled and whistled in him and around him; it was just the kind of frosty weather a snow man must thoroughly enjoy. But he did not enjoy it; and, indeed, how could he enjoy himself when he was stove-sick?

“That’s a terrible disease for a snow man,” said the Yard Dog. “I have suffered from it myself, but I got over it. Off! Off!” he barked; and he added, “the weather is going to change.”

And the weather did change; it began to thaw.

The warmth increased, and the Snow Man decreased. He said nothing and made no complaint—and that’s an infallible sign.

One morning he broke down. And, behold, where he had stood, something like a broomstick remained sticking up out of the ground. It was the pole round which the boys had built him up.

“Ah! now I can understand why he had such an intense longing,” said the Yard Dog. “The Snow Man has had a stove-rake in his body, and that’s what moved within him. Now he has got over that too. Off! Off!”

And soon they had got over the winter.

“Off! Off!” barked the Yard Dog; but the little girls in the house sang:

“Spring out, green woodruff, fresh and fair;

Thy woolly gloves, O willow, bear.

Come, lark and cuckoo, come and sing,

Already now we greet the Spring.

I sing as well: twit-twit! cuckoo!

Come, darling Sun, and greet us too.”

And nobody thought any more of the Snow Man.

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen – Illustrated by Arthur Rackham

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen – Illustrated by Arthur Rackham Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales – Illustrated by Rie Cramer and L. A. Govey

Hans Andersen’s Fairy Tales – Illustrated by Rie Cramer and L. A. Govey