The Gamekeeper’s Daughter – A Christmas Story

A pocketful of sweets, an encounter with Santa Claus, and a Christmas morning full of presents.

The Gamekeeper’s Daughter

– A Christmas Story –

“JUST run up to the Grange and tell her ladyship the bull-pup is doing nicely, and that you bandaged its leg as she showed you. Make haste, lass, if you’re not too tired, as her ladyship would like to know before she drives out.”

“All right, Dad; I’ll run. It’s much too cold to walk.”

Rogers, the gamekeeper, glanced with pride after the little retreating figure, and then, as his old mother was standing in the draughty porch awaiting him, he kissed her wrinkled face, and they entered the cottage together.

Nancy was soon at the Grange, her cheeks aglow under the scarlet hood of her cloak. New people were at the big house, and there seemed a deal of bustle going on. She waited in the vestibule and stared at the brightness, at the beautiful pictures and decorations where, ever since she had known the Grange, all had been damp and decay. She had never seen anything like this before, and she was enjoying the novelty, mixed with awe at all the grandeur, when a little girl richly dressed, about three years old, ran up to her. Nancy dropped a little bob of a curtsey, as her grandmother had

taught her to do to the gentry.

Little Iris was not at all shy, and was full of one thought only—the thought of Christmas—so that she burst out with: “D’you know tomorrow’s Christmas Day?” and, without waiting for a reply, she babbled on: “I’m going to have such boo’ful things—a dolly that sends kisses, a pamberlator for her to ride in, a gold watch with real ticks, and a titten with real scratches. Guess who’ll bring them.”

“Her ladyship?” ventured Nancy, dazzled at such a haul of magnificence.

“No, not Mummy,” exclaimed Iris, capering with delight and revealing more of her frills and laces.

“I can’t guess, Miss,” said Nancy, smiling through her diffidence—which was just what Iris wanted her to say.

“It’s Santa Claus! Santa Claus always brings me just what I want. Isn’t it clever?”

“Who’s Santa Claus? Is it your aunt, Miss?”

“I’m ’peaking to you about Santa Claus—a gen’lman. I’ve not seen him—never been able to catch him yet.”

“Catch him! But who tells him what you want?” She was getting quite interested.

“The little bird.”

Nancy felt completely mystified. What a different world this seemed to hers!

“What toys are you going to get?” continued Iris.

“Oh, no toys. I live in the cottage in the forest. Dad is always so busy, and I help him look out for poachers—so I have useful presents, I don’t have toys. Granny gave me this warm cloak last year; and then, Dad’s pockets get so full of sweets that they last for months.”

“Sweets and useful things aren’t p’esents,” said Iris, surprised. “Poor little girl! Wouldn’t you like toys?” she added.

“I think so, Miss—at least, I’ve not seen many. Cousin Janey has a skipping-rope and a workbox, but she won’t let me touch them.”

“Ah! you’ve been here long enough, Iris darling. I hear Nurse calling you,” exclaimed a soft voice, and her ladyship, with a kindly look at the visitor, laughingly caught up her little daughter in her arms before the child even knew she was there. Then she received the message, gave the little messenger a slice of cake, and in a moment Nancy was leisurely munching the fee as she trudged her way back on the grass through the frosty park. The dusk was gathering, when suddenly in the stillness she heard a dull thwack as of a stick against a branch—which caused her to stop and listen. She knew what the sound meant.

“That’s one of those poachers: he’s knocked down a pheasant, I’ll be bound!” said the gamekeeper’s daughter to herself. “I’ll just be after him!” and, gathering her skirts close around her, she crept through into a thick plantation. She had the intrepid fearlessness of her father, whose companion on his rounds she had been, when no danger was thought to be afoot, ever since she was old enough to ride pickaback. It came quite natural to her to help him, and though the old grandmother grumbled at her boyish ways she said nothing, for the child was obedient enough, and could

read and write and sew; and, moreover, her son would brook no interference with his treasure—especially since her mother had died.

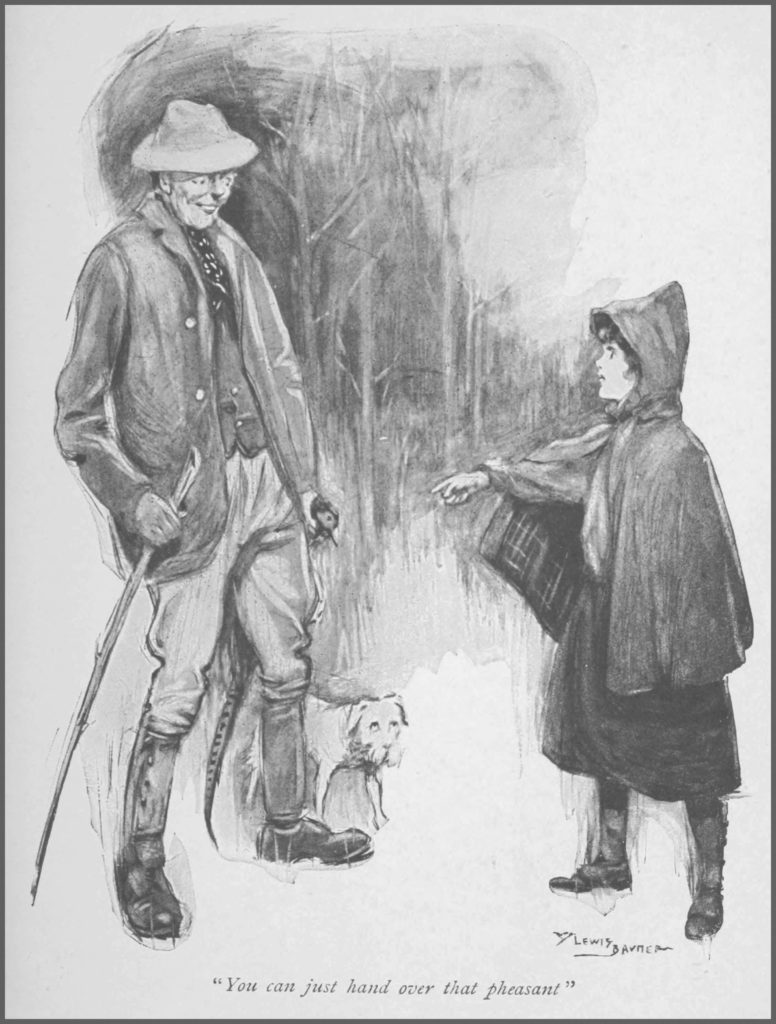

“Drop that!” cried Nancy. “Who’s there?”

Hearing only a girl’s voice, a rough-looking fellow emerged grinning from behind a tree, with the dead bird he had just picked up in his hand. A limp bag was slung over his shoulder, a stout staff was in his other hand, and a snarling “lurcher” dog slunk at his feet.

“Steady, Muffins!” said the man, giving the cowering animal a gentle kick as a reminder. “Now, Missy, what can I do for you?”

“You can just hand me over that pheasant. Ah! it’s you, is it? I know you, Tom Grollins, and I’ll report you to the gamekeeper.”

The poacher gazed at her stupidly for a moment. “Give you the blessed bird and be reported too, Missy? Come, that ain’t ’ardly fair, is it? (Will yer lie down, Muffins?) Now look ’ere. If I give yer the bird, will y’promise not to say a word as it was Tom Grollins—on yer davey, now? Will y’promise, Missy?”

She nodded. Tom Grollins was not very strong of intellect, and he was a known coward, and as the sound of a carriage was heard close by, the bargain was hastily concluded; the pheasant was handed over without further parley on the undertaking of the promise—“No names.”

The promise, of course, Nancy faithfully kept when she delivered to her father the bird she had demanded with such pluck and authority, and told him how she had got it. The gamekeeper laughed, remarking that he wouldn’t press her, but could make a pretty shrewd guess if he chose. However, she was worth her weight in gold, he said, and he patted her on the head for a trump—and Nancy felt uncommonly proud. But she didn’t quite understand what he meant when he said that terms such as she had made would not be quite approved of by the Lord Chancellor.

Then as Granny came in Nancy told of all she had seen, and of all the wonderful presents the tiny lady at the Grange was going to receive at Christmas, because she wanted them; and that a gentleman staying at the house called Mr. Santa Claus gave them, and knew what to get, because a bird—a parrot, she supposed—had heard and told him what the little lady wanted.

That night when Nancy was in bed she could think of nothing else but Santa Claus and the wonderful toys; and the thoughts were just beginning to get confused with a greatly envied skipping-rope and workbox, when she suddenly sat bolt upright in bed wide awake.

Her room was a tiny one leading off the kitchen, and in the moonlight she had just seen Tom Grollins pass by—this time with a full bag on his back, and the faithful Muffins was close at his heels.

“Well, I never did!” exclaimed Nancy, in her astonishment and vexation unconsciously quoting her grandmother; “I never did! Now what’s to be done? Gran’s no use—Dad’s out. But Dad’s sure to find that wicked poacher,” she reflected, on hearing the clock strike nine: “he’s in the forest, and can’t be far.” And she lay back, relieved at the thought that her father had suspiciously refused the invitation of a shabby, gaitered, and very doubtful sportsman, to drink Christmas in with mulled beer at the village tavern. She had heard her father remark afterwards that he wanted “to be

within earshot of gunshot.” So she wouldn’t worry, for Tom wouldn’t get the things after all.

After a time Nancy changed her mind. As in a dream, but not feeling a bit sleepy, she quickly donned her cloak, stealthily opened the kitchen door so as not to disturb the old lady, and hastened out into the night. Curiously enough, she didn’t feel cold in the bleak air—and in her hurry she never even noticed she was without shoes or stockings.

In front of her was a man, and she quickened her pace. She soon overtook him—sooner than she expected, for dark clouds overshadowed the moon, and she was at his side before she knew it.

“Tom Grollins!” she exclaimed, breathless and indignant: “how dare you! I’ve caught you again!”

“I’m not Tom Grollins,” replied her companion in a deep, manly voice, in which a funny chuckle seemed to rumble.

For a moment the child hesitated. It certainly didn’t sound like Tom Grollins’s whiny treble, but then—perhaps he was pretending, so as to put her off.

“Yes, you are,” she retorted firmly. “Now, what are you doing here?”

“It’s a secret.”

“You’re after poaching again. I shall report you to Dad. And,” she added severely, “you’ve just got to give me this very minute all you’ve got in that bag.”

“All in my bag? Softly, softly: wouldn’t that be highway robbery, with threats?” answered the jolly voice, and with a laugh—“Oh, greedy!”

Nancy stopped and stared hard, but it was too dark for her to see him, as she had done from her bed. He had stopped too.

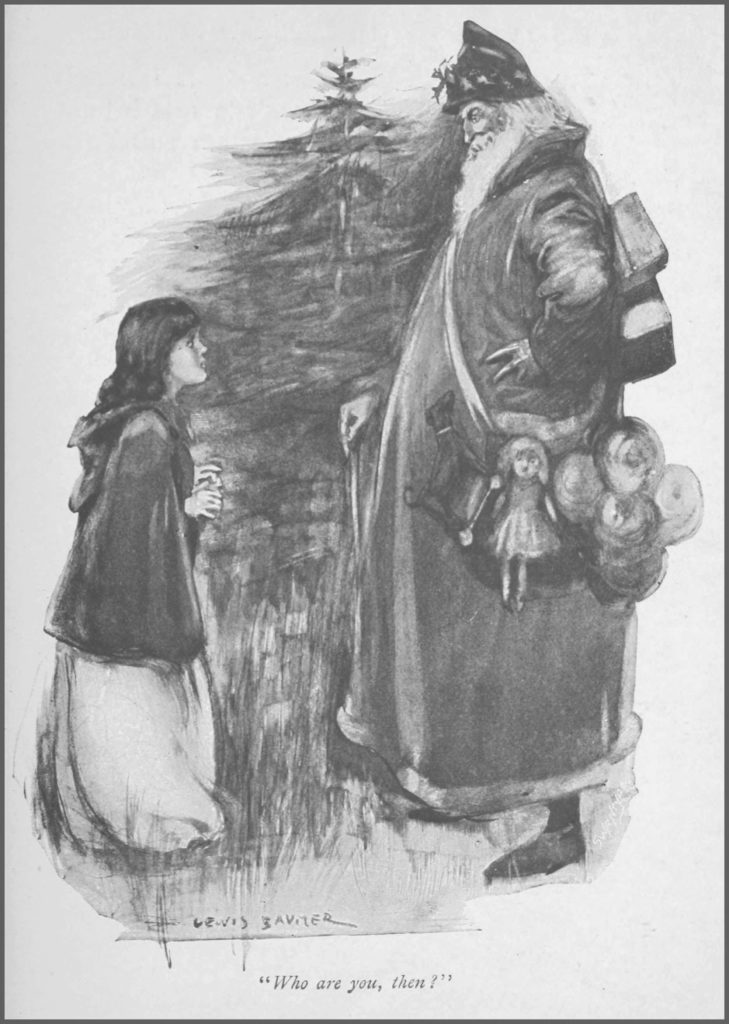

“Who are you, then?” she asked lamely.

“Santa Claus,” came the reply.

“Santa Claus!” repeated the child in astonishment.

The dark cloud-wrack happened to part, and Nancy saw towering above her the dearest and most imposing old gentleman imaginable, with a large smiling face and long white beard. White curly hair fringed his holly-decked scarlet cap, and his long, loose, red coat revealed here and there glimpses of scarlet plush beneath. Instead of rabbits and pheasants, he was laden with the newest of toys; and as to Muffins, he was nowhere to be seen—unless he was that toy-dog dangling from the overflowing bag, and wearing a leather collar with bell attached, and a leather muzzle that

ought to allay the fears of the most nervous.

“Yes, little woman, I am Santa Claus—himself!” he repeated, with his jolly chuckle.

“I—I—beg your pardon,” stammered Nancy, quite confused.

“It’s all right,” he replied good-humouredly. “Now shall I see you home before I continue my rounds?”

“Oh, may I come with you?” The words had dropped out of her mouth before she could stop herself.

Santa Claus shook his head. “Come with me, indeed? I should think not! Come with me? ’Pon my word!” Then he hesitated and smiled, and said kindly, “Well, come along, dear. You’re a good, brave little girl. But you must know I’ve never made such an exception before. However, it’s so odd to find a child who doesn’t know me—even such a little village mouse as you—that we must really make one another’s acquaintance.”

He drew Nancy under his cloak to keep her extra warm, and to hide her from view, and he showed her how she could peep out. Then he took her by the hand, and the quaint pair proceeded along the mysterious-looking forest until they came to the part Nancy loved best. There, heaps and heaps of fir-trees grew, the tall ones protecting the wee ones, and the wee ones doing their best to try and grow tall too.

Santa Claus stood still, and looked around, as if in preparation of some important matter. Nancy felt something was going to happen, and she peered up into the face of her guide. “Father Christmas has come!” he proclaimed loudly at last.

And then what a change there was! The fir-trees all became Christmas-trees, lighted each one—big and little—with candles, blue or green, yellow or red, each burning with the same coloured light. And from the diamond-frosted branches hung toys innumerable. At the top of each tree stood triumphant a fairy-doll with wand outstretched.

Nancy clasped her hands with rapture at the sight. “Oh, Santa Claus!” was all she could exclaim.

He lifted her on to his shoulder, and let her gaze until she had gazed enough. Now, indeed, she realised what toys were—whence they came, and how they grew.

Then she felt he was carrying her away, and her heart beat with curiosity and excitement, for she knew Santa Claus was proceeding on his rounds to pay visits to all the sleeping children who deserved it, while she was clinging to his dear old neck, and would see all that went on.

The first visit was to Iris at the Grange, whither Santa Claus was already on his way. They entered the pretty bedroom, where the spoilt little lady was smiling in anticipation in her sleep; and the “dolly, pamberlator, watch, and titten with real scratches” (immovably asleep) were all produced as though by some conjuring trick from Santa Claus’s basket or deep pockets, and duly placed to meet the child’s eager glance on her waking.

“Mr. Santa Claus,” whispered Nancy, who had been wondering all the time, “how did we get here?”

“Chimney!” he whispered back.

“Chimney?”

Santa Claus nodded.

This didn’t make her much wiser, for to her knowledge she had never seen the inside of a chimney in her life; but she forgot to pursue the subject now that something more interesting was going on.

Iris had vanished, and a pale little boy lay asleep in a room above a flower shop.

“He doesn’t care for toys,” whispered Santa Claus; “he loves that pink geranium by his side.” And a gaily painted watering-pot was placed next to his flowering possession. “How white in comparison with the blossom the suffering, pinched little face looks on the pillow!” thought Nancy; “he will be pleased.” Before they left, Santa Claus filled the can with water from the cracked toilet jug.

In the large house across the way were sounds of bright music—a party was going on.

“I’m afraid it’s too early to go there yet,” said Santa Claus, consulting his great watch. “However, we’ll go and see; it’s really high time for all youngsters to be in bed.” In the night-nursery were two cots. Both were empty. “I must call on my way back,” he said.

Just then the door opened, and childish voices were heard shouting: “Santa Claus! We’ll catch him if we’re quick!”

And there was only just time for the two travellers to disappear before the lights were turned up and the owners of the cots rushed in.

“Nearly caught that time!” exclaimed Santa Claus, as they proceeded on their way (it was extraordinary how alert and agile he was for such an old and portly gentleman), and he burst out into a loud laugh, and only recovered from it as they entered a long room full of small beds. It was decorated with holly and mistletoe. A light burned at one end, where sat a pleasant-looking nurse half-screened in the corner by the fire.

Nancy followed Santa Claus’s movements with breathless interest as he flitted to each little sleeping occupant of the hospital ward—for such it was—placing here a toy horse of skin and harness with a long wavy tail; there a lovely picture-book with a green cover, on which the title was printed in large gold letters.

Twice only did Nancy heave a little sigh, quickly repressed, and her eyes filled with longing: once when a skipping-rope was loosely tied round the clasped hands of a little girl who was convalescent, and was going to leave, as Santa Claus explained; and once again when, creeping on tiptoe, he placed under the chair of the dozing nurse a very smart workbox, with the name engraved on top.

Every now and then Santa Claus would linger to smooth the look of pain from a little suffering face into a smile, or touch with his cool palm a little fevered hand.

As she trotted round with him, tears of pity and happy sympathy filled Nancy’s eyes, and she tried to give Santa Claus a good hug—only she couldn’t reach half-way round—while he tenderly wiped those tears on his big cuff, and carried her off, a long way, to a very poor cottage. There they peeped round from behind the door.

Everything looked bright, and sounded happy too, and every now and again, amid the laughter and the chatter, the arrival of Santa Claus was gaily prophesied. Three little girls were dancing round three of those tiny decorated Christmas-trees Nancy had seen that eve, and their parents, looking on happily, echoed their exclamations of joy. She was surprised to see so much jollity in so poor a place; but Santa Claus didn’t seem to be so—he merely muttered, “It’s all right this year!” and withdrew with her the same way they had come.

“And now,” remarked Santa Claus cheerily, “before I go back to the party children or do anything else I must visit all the other hospitals. I’ve brought you home because you must be very tired, little woman. I’m terribly busy to-night—half afraid I shan’t get it over in time: just think of the disappointment if I don’t! So good-night, Nancy! Pleasant dreams! A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!”

And his kind face bent over her in bed, as it had over so many others that Christmas Eve; and as he pressed her hand he added, with a smile, “I’ve a terrible lot to do, and I mustn’t forget anybody!”

The dawn heralded once again a Christmas Day, and when the sun peeped forth he awoke Nancy. She looked round, and uttered a cry of surprise and delight. For before her astonished eyes she seemed to see a little fairy-land all to herself. Grouped about her bed were a skipping-rope, a workbox—both handsomer than Janey’s—and a little box besides. She couldn’t believe they were real, so she felt them all over, and not only found they were quite real, but the little box when it was touched sent forth the most lovely, mysterious music.

“Dear, kind, darling Santa Claus!” exclaimed Nancy. Then she saw that beside them there was also a plum pudding with a Christmas card attached, from the new mistress of the Grange. What was puzzling was that on a chair close by hung three pairs of her father’s new socks with a paper asking her to mark them; but they were marked already, and were full of good things to eat.

Never in all her nine years had Nancy had such a Christmas. After saying her morning prayers, she sat down at the table, where, with elbows outspread and her little tongue peeping out as she moved her pen, she wrote the following letter:—

“DEAR MR. CLAUS,—Thank you very much for those lovely presents: I like them

very much. And thank you for the lovely time I had going about with you

last night. I shall never forget it. Please forgive me for thinking you

were the wicked poacher, Tom Grollins. I must now say good-bye.

“I send you 200 kisses (x x x etsetra).

“Your grateful little friend,

“NANCY ROGERS.”

And then she addressed it to him at the Grange.

When Nancy had stamped and posted it, her grandmother and her father came in to breakfast, and received Nancy’s grateful thanks, for she wore a pretty new frock. Then she told them that as she had hurried back from the post-box, so as not to be late for breakfast, she had heard the head gardener say to the butler that Tom Grollins had been seen that night striding quietly along with a big bag well stuffed.

“But, Dad,” continued his daughter with conviction, “it isn’t true. I’m sure it’s a mistake.”

“Why isn’t it true, lass?” inquired her father. “It’s likelier to be true than not.”

“Because I made the same mistake myself,” said Nancy.

“Well, it would take a good deal to persuade me that my little meeting with that slippery rascal turned out to be a mistake!” exclaimed the gamekeeper, as he set down his cup and smiled with satisfaction. “When did you meet him, little woman?”

“Last night.”

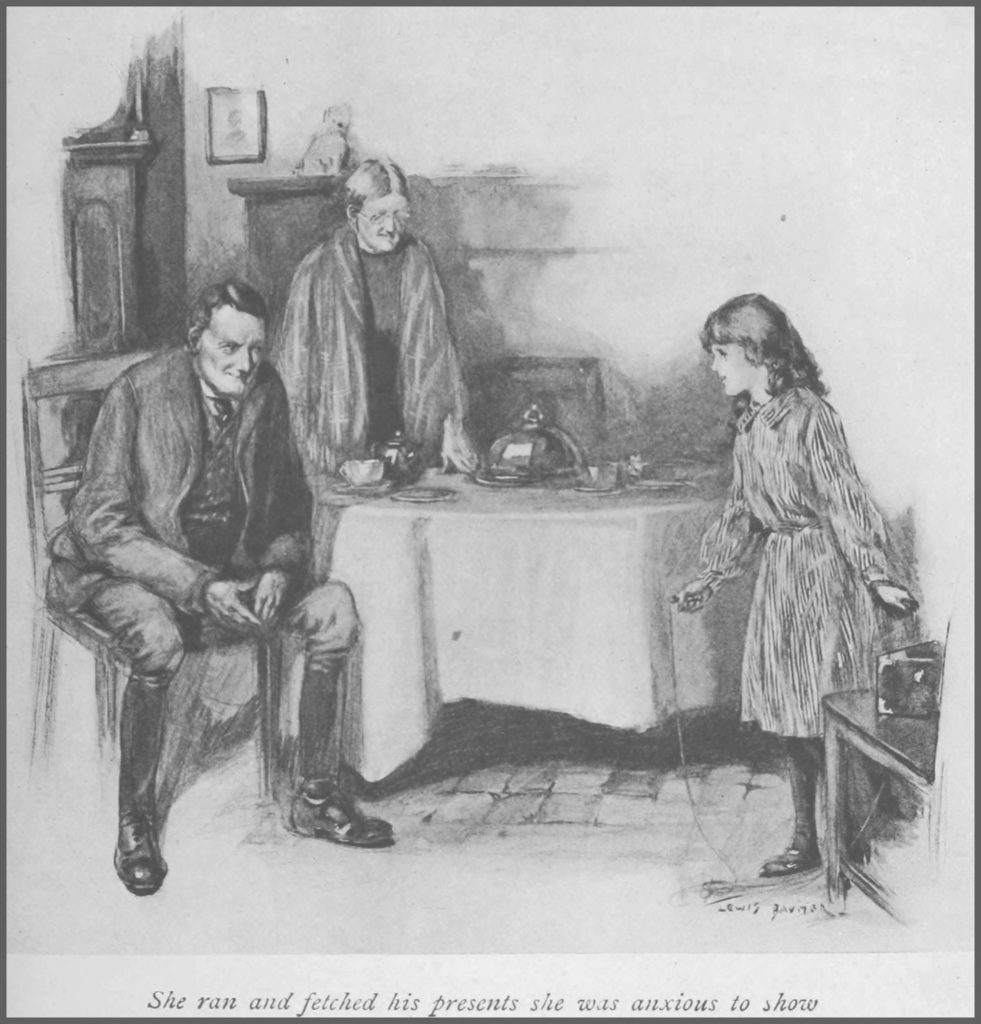

“And who do you fancy it was, dearie?” asked the old grandmother.

“I know who it was, Gran. It was Mr. Santa Claus!” As they smiled still, she ran and fetched his presents she was anxious to show.

And Nancy knew she was right, and that it was Santa Claus, for nothing more was heard of the poacher Tom Grollins for ever so long, and every one Nancy asked seemed to know all about Santa Claus having been on his rounds that night—even those who hadn’t seen him.

This story was taken from the book:

Read more Christmas Stories here: