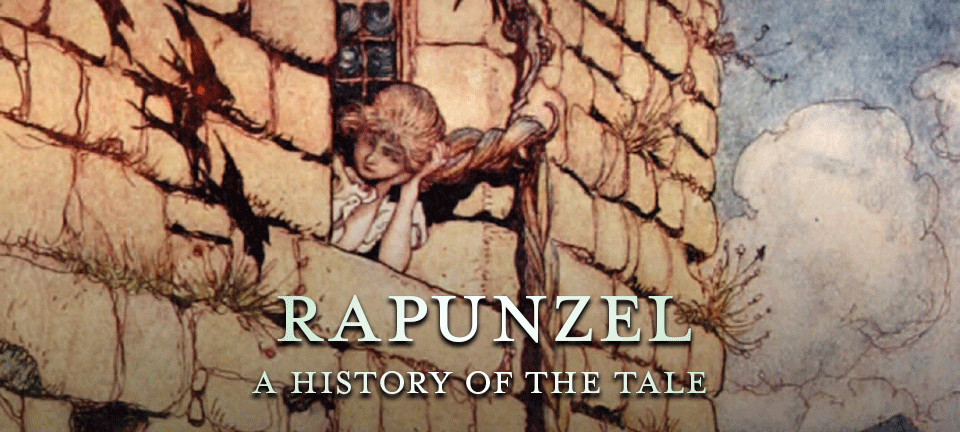

The History of Rapunzel

The story of a beautiful young woman with long flowing hair, who – after a period of trials and tribulations finally reunites with her true love, it first appeared in print with Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone (1634 – 1636).

Unlike many fairy tales, the classic ‘Rapunzel’ narrative actually has a reasonably short provenance. As the story of a beautiful young woman with long flowing hair, who – after a period of trials and tribulations finally reunites with her true love, it first appeared in print with Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone (1634 – 1636). This story, with the title of Petrosinella (meaning ‘Little Parsley’), largely set the tone for all who followed, including the Brothers Grimm, Charlotte Rose de Caumont de la Force, and Andrew Lang. Despite this seeming creation ex nihilo though, there are some identifiable precedents which bear a striking similarity to Basile’s tale.

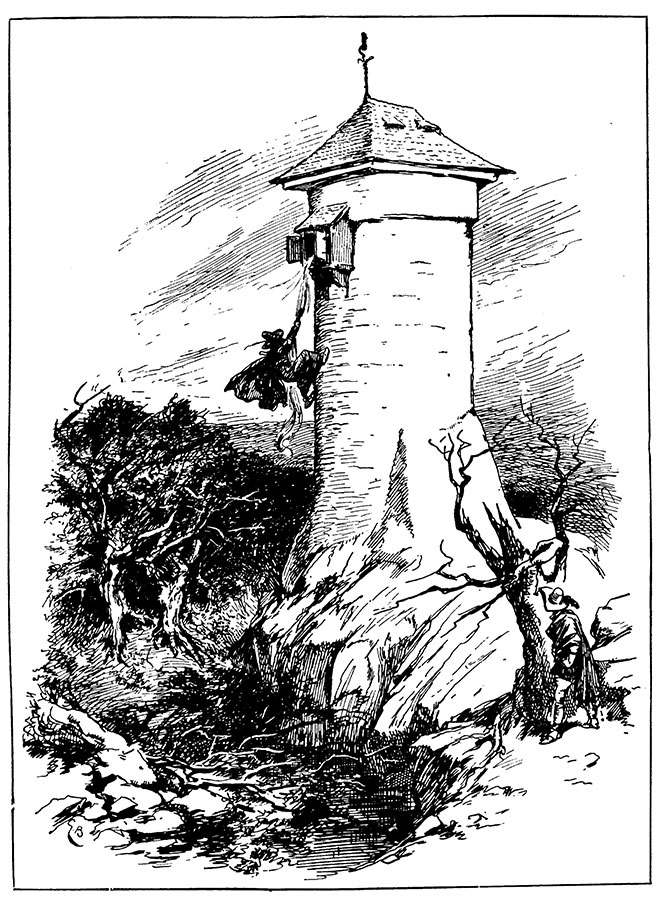

The first of these is the legend of Saint Barbara, a third century holy lady who is thought to have lived in third century Nicomedia (present-day Turkey), or in Heliopolis of Phoenicia (present-day Lebanon). Her story was written down by Jacobus de Voragine, the Archbishop of Genoa (1230 – 1298) and published in the Legenda Aurea (1275). According to the legend, Barbara, the beautiful and intelligent daughter of a wealthy Pagan, was locked in a tower by her father – who intended to protect her from the world outside. During her time in captivity, she converted to the Christian religion and subsequently was tried before a court and eventually executed by her own father. Unlike later ‘Rapunzel’ narratives, Saint Barbara rejected proposals of marriage put to her by her father, instead focusing her devotions on the Holy Trinity of the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit.

SELECTED BOOKS

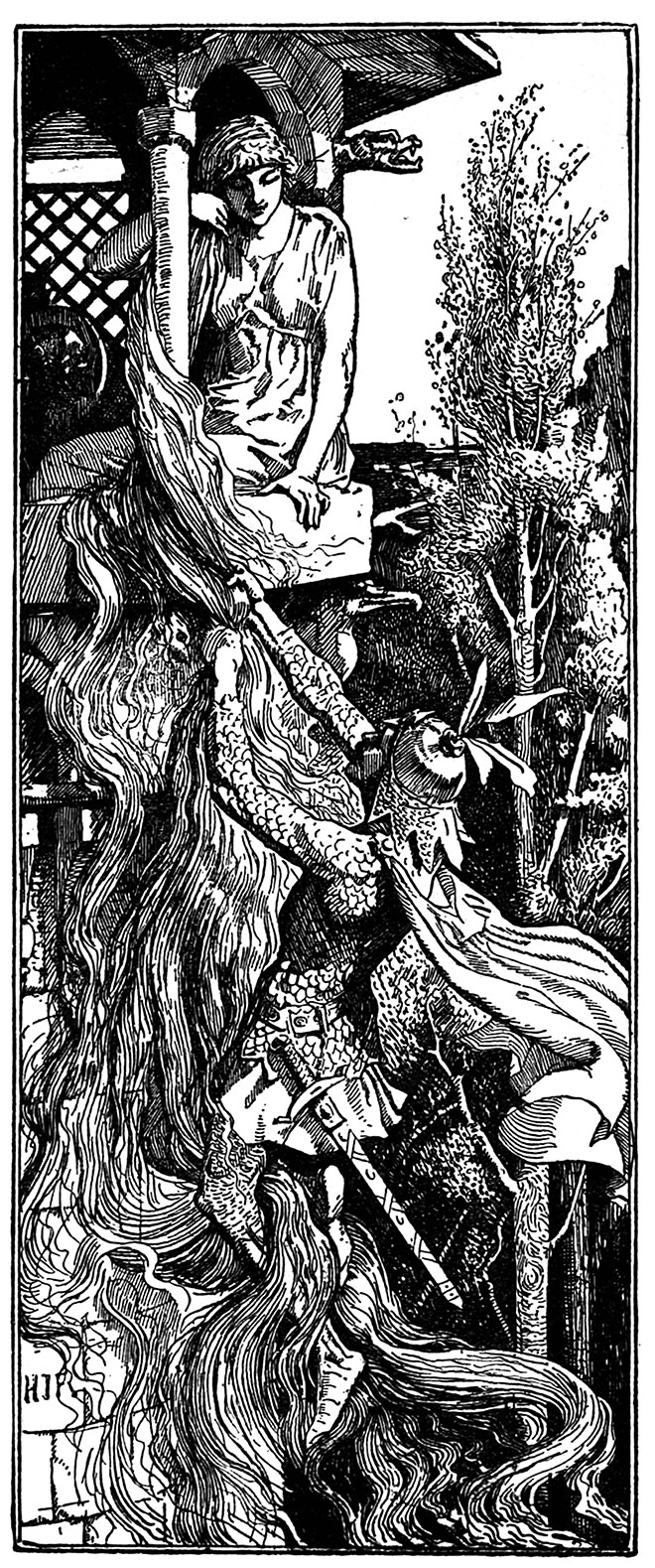

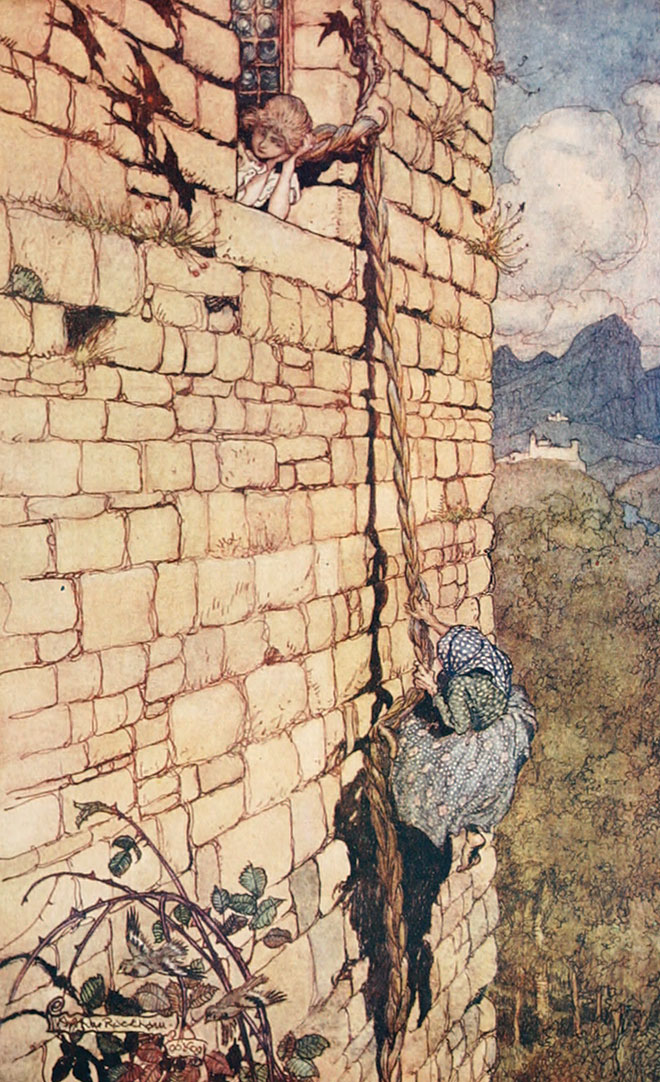

The second early precedent is the tale of Rúdábeh and Zál, from the ancient Persian epic, The Shahmaneh (‘The Book of Kings’). This story, unlike the Legend of Saint Barbara is the first tale to mention the young maiden’s long hair. Written around 1000 CE (and consisting of some 60,000 verses), the romance of Rúdábeh and Zál is recounted in the section devoted to ‘The Age of Heroes’. Just as later versions of the heroine’s name are highly significant, the word Rúdábeh comes from Rood, meaning ‘child’ and Ab meaning ‘shining’; the shining child. Unlike Barbara, she is not kept in a tower against her will, but decamps there in order to meet with her true love, Zál. To allow him to climb up onto her balcony, Rúdábeh casts down her luxuriant hair, which Zál quickly ascends. All subsequent versions of the narrative (apart from the Philippine tale of Juan and Clotilde) mention the young woman’s flowing tresses.

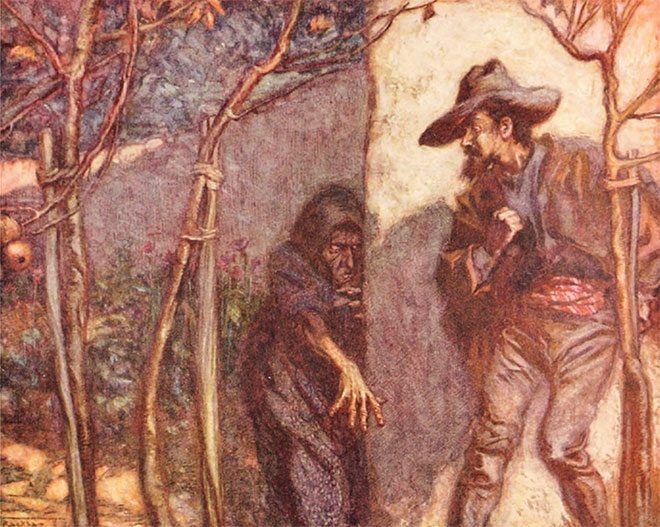

When considering these two tales in combination, it is easier to see how Giambattista Basile’s Petrosinella came about. It contains the characteristic tropes of many later accounts, including the pregnant mother who craves some parsley from the ogress’s garden. In the Brothers Grimm’s story, this aspect is transformed into ‘rapunzel’ (a type of lettuce) taken from a sorceress, and in Andrew Lang’s ‘Prunella’, it is plums, taken from a witches’ orchard. From a scientific interpretation the ‘evil’ character can be portrayed as a witch or medicine woman, who had mastered the use of remedial plants capable of saving the mother from the complications of pregnancy. Such complications were of course, an incredibly common event in seventeenth century Europe.

This seemingly uneven bargain (with the unfortunate woman’s first born offered in return for the item of food) is a common trope in fairy tales; replicated in Jack and the Beanstalk, when Jack trades a cow for beans and in Beauty and the Beast, when Belle comes to the Beast in return for a rose. Folkloric beliefs often regarded it as quite dangerous to deny a pregnant woman any food she craved, and consequently family members would have gone to great lengths to secure such cravings. Such desires on the woman’s part indicated a lack (especially prevalent in the lower, farming classes) of much needed vitamins – highlighting the tale’s humble beginnings.

Basile’s Petrosinella was subsequently adapted by the French aristocrat and writer, Charlotte Rose de Caumont de la Force (1654 – 1724), and published as Persinette (again, translating as parsley) in 1698. This version was incredibly similar to the original Italian, excepting that the ogress is this time a fairy, and the pair of lovers find their escape much more difficult. This French variant was then translated into German in the late 1700s, by Friedrich Schulz – a tale which then went on to inspire the famous Brothers Grimm.

The Grimm’s version was also very similar to French tale of Persinette. Published in their 1812 Kinder und Hausmärchen (‘Children’s and Household tales’), its title, ‘Rapunzel’ is the name by which the narrative is presently known world-wide. Like De La Force, they also added in a more ‘adult’ detail, in Rapunzel becoming pregnant with the Prince’s child (twins in the Grimm’s case). Basile’s story also described the prince and the maiden’s encounters in quite bawdy language, but did not directly suggest pregnancy before marriage.

It was mature particulars such as this which drew criticism from the Scottish folklorist, Andrew Lang. Lang consequently referred back to Basile’s original, but took the story in a different direction again, publishing ‘Prunella’ in The Grey Fairy Book (1900). In this version, Prunella is set a series of impossible tasks by the witch – but is aided in her endeavours by the witch’s son, who only asks for a kiss in return.

The good and chaste Prunella refuses each time, but eventually realises her true affections for the young man, after he kills his own mother (in order to save Prunella). Whilst still a rather gruesome ending, the murder of a wicked witch was considered more fitting for young audiences.

It was preferred over depictions of a young woman disobeying the orders of her elders, by giving herself willingly to the ‘prince’. Like the strong-willed Saint Barbara, the ‘Rapunzel’ character is anything but a meek and obedient princess.

As a testament to this story’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, Rapunzel continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums.

Its classic line, of ‘Rapunzel, Rapunzel, let down your hair!’ has since become an idiom of popular culture. The tale has been translated into almost every language across the globe, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.

Rapunzel – And Other Fair Maidens in Very Tall Towers

Rapunzel – And Other Fair Maidens in Very Tall Towers