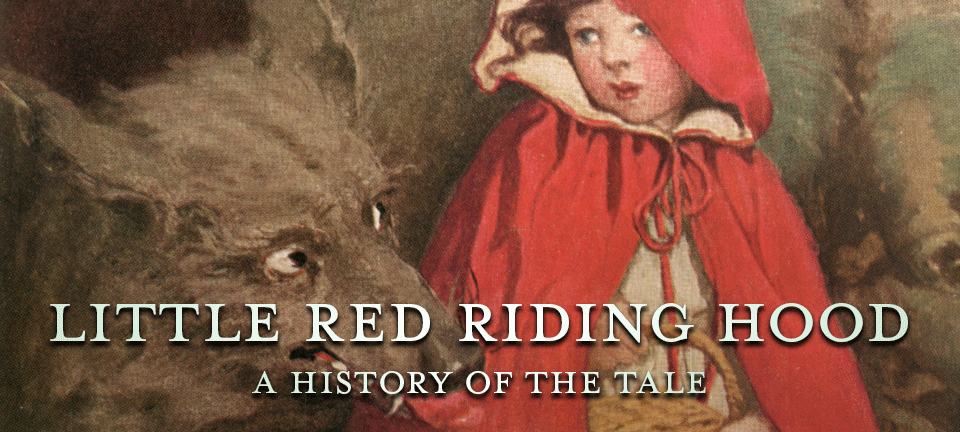

The History of Little Red Riding Hood

Despite its ubiquity in the modern day, as fairy tales go, Little Red Riding Hood has a relatively short history. It is a European folktale, first written down in the form we know today in the seventeenth century.

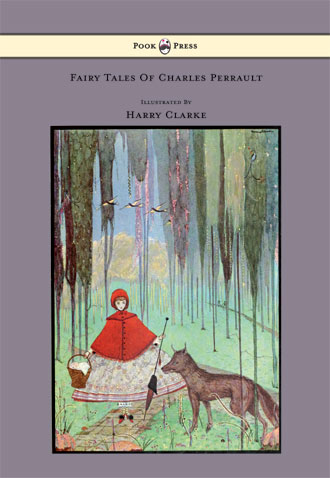

Little Red Riding Hood is one of the world’s best known fairy tales. It provides the name for the tale type classified as Aarne-Thompson index; no.333. Despite its ubiquity in the modern day, as fairy tales go, Little Red Riding Hood has a relatively short history. It is a European folktale, first written down in the form we know today in the seventeenth century. Most scholars date the first ‘fixed’ version as Charles Perrault’s Le Petit Chaperon Rouge (1697). The Brothers Grimm provided a slightly differing account in their Kinder und Hausmärchen (‘Children’s and Household Tales’) in 1812. Yet despite these ‘modern’ beginnings, it is possible to trace a far longer lineage of the narrative form. At its core, the story involves a young girl (generally walking a forest, wearing a red cap or cape) who, at some point, encounters a big bad wolf character.

The theme of a ravening creature, and a person released unharmed from its belly is prevalent in many other tales. It appears most famously in the biblical story of Jonah and the Whale, as well as in the story of Saint Margaret. In the latter tale, the saint emerges unharmed from the belly of a dragon. A similar narrative is also evidenced in the character of Cronus in Hesiod’s tales (700 BCE), who swallows then disgorges his children alive.

SELECTED BOOKS

Aside from such broad themes, the direct origins of the Little Red Riding Hood Story can be discovered in stories told by French and Italian peasants in the tenth and fourteenth centuries. Whilst very few of these were written down in their full form, there is a version noted by the French folklorist Achille Millien. This is of an Italian tale named La Finta Nonna (‘the false grandmother’). The story recounts the rather gruesome tale of a girl’s encounter with a wolf (who has killed her grandmother), who then feeds the young lady her grandmother’s blood and flesh. The girl only manages to escape by excusing herself to go to the bathroom.

Whilst this story has very obvious similarities to the version of Little Red Riding Hood we know today, some have argued that the tale has had a far wider geographical reach. There have been examples found in China from the Quing Dynasty (1644-1912), most notably the narrative of ‘Grandaunt Tiger.’ In this variant, a panther or a tiger (in a similar manner to the ‘wolf’ creature) persuades the children to let her in the house, claiming to be a grandaunt or grandmother.

These early variations of the tale differ from today’s popular narrative in several ways. The antagonist is not always a wolf, but sometimes an ogre or a ‘bzou’ (werewolf). The unwitting cannibalization evidenced in the early Italian version disappears in later, slightly bowdlerised variants. Interestingly in these stories, the young girl escapes without any help from an older male or female figure (in most cases the huntsman). Instead, she uses her own cunning.

READ LITTLE RED RIDING HOOD TALES NOW

Having said this, some scholars have argued that Little Red Riding Hood in fact originates from a far simpler tale. This is ‘The Wolf In Sheep’s Clothing’, which appears in Aesop’s Fables. Aesop (who lived in ancient Greece between 620 and 560 BCE) describes a wolf that resolves ‘to disguise his appearance in order to secure food more easily.’ But on meeting an untimely end, the wolf also provides the moral of ‘Harm seek. Harm find.’ The harm met by Aesop’s wolf is not matched in Perrault’s 1697 version (in which the young girl remains unsaved), but is reflected in the Brothers Grimm’s Rotkäppchen. In the Grimm’s story, the huntsman rescues the grandmother and the girl by cutting open the wolf’s belly with a pair of scissors.

Such was the consternation over these differing endings, that Andrew Lang (an English story-teller) explicitly stated in his version that the tale had been previously mis-told. In his variant, The True History of Little Goldenhood (1890), the girl is saved not by the huntsman, but by her own hood. As with all folkloric stories, the origins are mixed, but Lang most likely derived his tale from another French author, Charles Marelles.

Although Perrault’s ending differs considerably from Aesop’s original tale, the French author still felt that his story contained an obvious moral. From the narrative one learns that children (especially young ladies) do very wrong to listen to strangers. And consequently, it is not unheard of if the ‘wolf’ is thereby provided with his dinner. These wolves represented the men of Paris, who innocent young girls should avoid:

I say Wolf, for all wolves are not of the same sort; there is one kind with an amenable disposition – neither noisy, nor hateful, nor angry, but tame, obliging and gentle, following the young maids in the streets, even into their homes. Alas! Who does not know that these gentle wolves are of all such creatures the most dangerous!

The sexual overtones of the story would not have been lost on contemporary readers, as the French idiom for a girl having lost her virginity was ‘elle avoit vû le loup’ (she has seen the wolf). In many of Little Red Riding Hood’s other variants however, the tale is merely meant to instill a general terror in young children of ‘the beast.’ The narrator was traditionally meant to make a pounce, in the character of the wolf, at their youngest listener.

As a testament to this stories ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, Little Red Riding Hood continues to influence popular culture internationally. It lends plot elements, allusions, and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. It has been translated into almost every language, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.

More on Little Red Riding Hood

SELECTED BOOKS