The History and Origins of Hansel and Gretel

Such tales, where a family’s offspring are abandoned (usually in the woods) are thought to have originated in the medieval period of the Great Famine (1315-1321), which drove many people to desperate deeds.

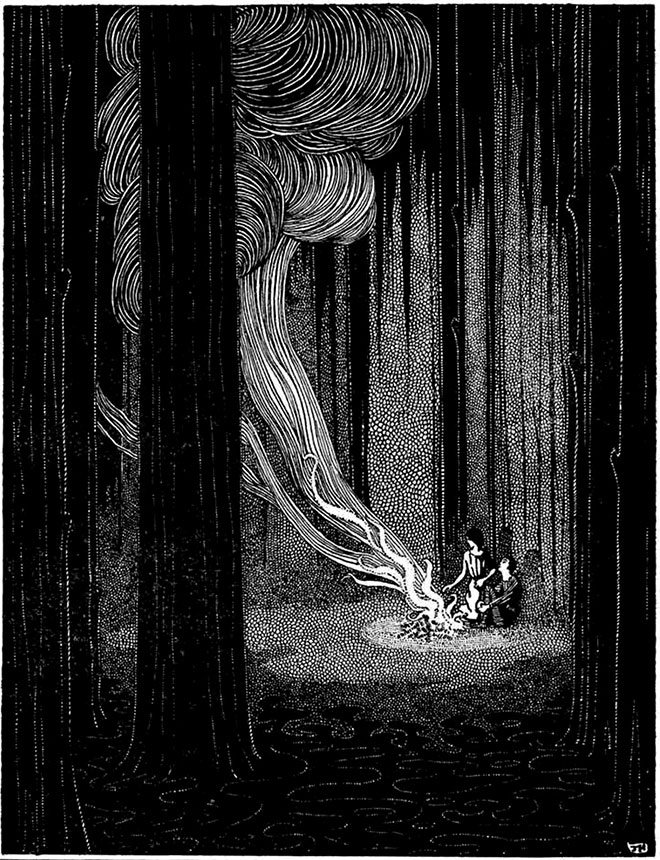

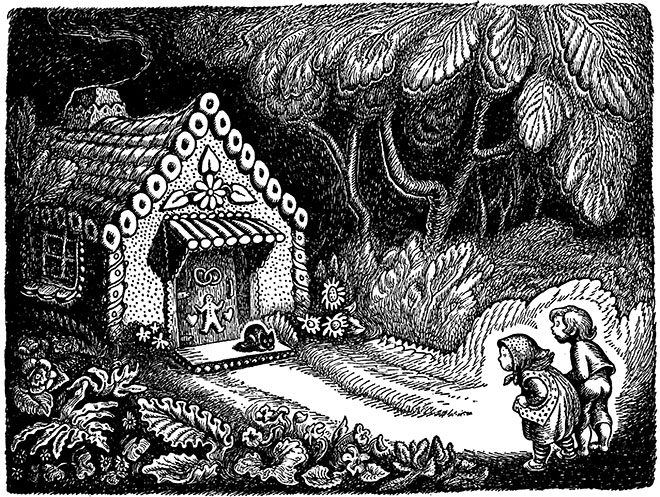

The origins of the Hansel and Gretel story has a reasonably short historical lineage. It belongs to a group of European tales especially prevalent in the Baltic regions, about children who outwit witches or ogres into whose hands they have involuntarily fallen. Such tales, where a family’s offspring are abandoned (usually in the woods) are thought to have originated in the medieval period of the Great Famine (1315-1321), which drove many people to desperate deeds. Deserting children in the forest to die, or leaving them to fend for themselves was certainly not unknown during the Late Middle Ages – and it is no small coincidence that the children are starving when they discover the gingerbread house.

The best known version of the story was published by the Brothers Grimm in 1812

Besides highlighting the endangerment of children (as well as their own cleverness), the ‘Hansel and Gretel’ tales all share a preoccupation with food: the mother or stepmother wants to avoid hunger, while the witch lures children to eat her house of candy, so that she can eat them. The best known version of the story was published by the Brothers Grimm, as Hänsel und Gretel in their Children’s and Household Tales (1812).

For the Brothers Grimm, collecting tales of distinctly Germanic origin was a way of preserving their own cultural identity at a time when the French Emperor Napoleon was taking over vast swathes of Europe. This was part of a more general trend in the nineteenth century, whereby folk stories garnered substantial interest, seen to represent a pure form of national literature and culture; deriving from the common folk (Volk). Although the brothers gained a posthumous reputation for collecting their tales from peasants, many of the stories actually have origins in middle-class or aristocratic acquaintances. Some of their better known narratives (Hänsel und Gretel included) were narrated by Henriette Dorothea Wild, the well-respected daughter of a pharmacist. Dorothea, or Dortchen as she was known to the brothers, later became Wilhelm’s wife.

A much earlier variant comes from Italy, penned by Giambattista Basile

In the Grimm’s original 1812 version of the tale, both parents agreed to send the children into the woods, but by 1857 it was the wicked step-mother who came up with the plan. Although the Grimm’s later story is the best known Hansel and Gretel plot today, a much earlier variant comes from Italy, penned by Giambattista Basile (1566 – 1632). Published posthumously, his fairy tale collection (Il Pentamerone) was in fact a key inspiration to the Brothers Grimm, who praised it highly as the first national collection of fairy tales. In Nennillo e Nennella, the cruel step-mother demands that the two children be put out of the house, but the father secretly leaves them a trail of oats, hoping they may find their way back. In a similar manner to the Grimm’s later tale (where the children’s breadcrumbs are eaten by birds), the father’s plan is quashed when the oats are eaten by a donkey. This aspect, of young protagonists attempting to find their way home via a self-made trail, is prevalent in many other folk-tales. It is most notably found in Charles Perrault’s Petit Poucet (1697) and Madame d’Aulnoy’s Finette Cendrillon (1721) – both of which the Grimms identified as parallel stories. Despite these initial similarities though, both Petit Poucet and Finette Cendrillon diverge substantially as the narrative progresses.

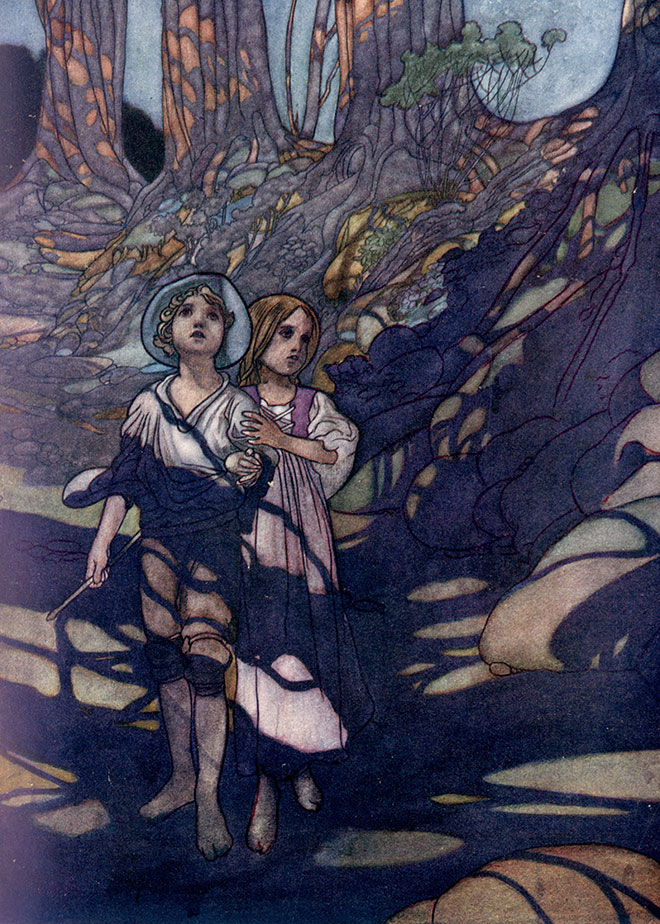

SELECTED BOOKS

What all of these early versions do have in common, is the basic aspect of survival – a remnant of the coming-of-age rite-of-passage extant in Proto-Indo-European culture. The family has a universal and basic role in all civilizations, and it is the breakdown of the traditional family unit that causes the problems in the Hansel and Gretel storyline. When economic hardship hits, the parents abandon their own children. Despite this initial abandonment, when the relatives are eventually reunited, peace and happiness once again return. This is a common theme to many fairy tales, for instance the Cinderella chronicle, where the young girl’s faithfulness to her mother’s legacy demonstrates the timeless virtue of loyalty to one’s kin. Or, more perilously, in the Little Red Riding Hood story where the young girl’s failure to heed her parent’s warning to stay on the forest path leads to disastrous results. Aside from this familial aspect, the forest was also an incredibly threatening place for early European societies. Although a source of food and shelter for many, it was also seen as a harbinger of magic and danger – a location where people normally did not travel

What all of these early versions have in common, is the basic aspect of survival

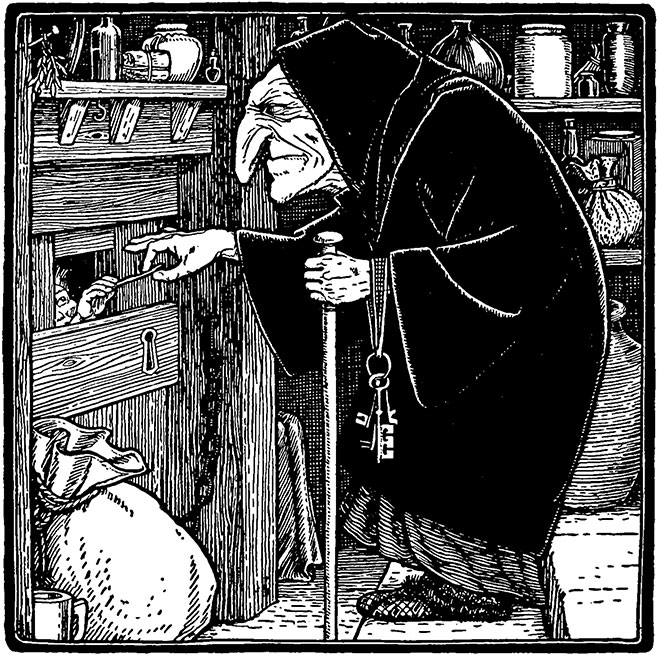

This explains why in so many variants of the Hansel and Gretel story, the witch (or in some cases, the ‘ogre’) is found deep within the forest. In the Russian legend, Baba Yaga (written down in Blumenthal’s Russian Folktales, 1903), the cannibalistic witch is also located in the mysterious woods. Correspondingly, in the Romanian tale of the Little Boy and the Wicked Stepmother (penned by Moses Gaster), the evil events also take place in the undergrowth. The Portuguese account of the Two Children and the Witch is the only exception, with the children coming across the witch just off a road, on the edge of the forest.

At the time of this story’s genesis (around the fourteenth and fifteenth centuries), belief in witches was commonplace. Between 1500 and 1660, a staggering 80,000 suspected witches are thought to have been killed in Europe, with 80% of those put to death being women. The oven into which the witch is eventually relegated, is also redolent of the fires of hell as punishment for her sins. As is perhaps evident from these examples though, Hansel and Gretel has an unusually small geographic reach when compared to many other folkloric tales, with most versions coming from Europe.

READ HANSEL & GRETEL TALES NOW

There are legends from other cultures with striking similarities to the ‘babes lost in the wood’ narrative, including Kadar and Cannibals from Southern India, and The Story of the Bird that Made Milk from South Africa. Though they do differ substantially from the European narrative structures, the African tale is the most similar. Although it does not include a ‘witch’ character, magical animals provide the supernatural element. It tells the story of three children, banished by their father after letting his magical milk-producing bird loose. Similarly to the European tradition, the children’s ostracisation is caused by the family’s sudden loss of food, and they subsequently flee into the wilderness. In an intriguing departure from the Grimm’s version, though in a comparable manner to Basile’s Nennillo e Nennella, the children do not return home, but enjoy lives of plenty – before eventually meeting their parents again. This time, the plot is reversed, and the children benevolently rescue the adults from a famine sweeping the country.

As a testament to this story’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, Hansel and Gretel continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions, and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. It has been translated into almost every language, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.