The History of Bluebeard

The tale of Bluebeard has an incredibly long and fascinating history. Unlike most fairy-tales, its origins can be traced to real events and people – horrific tales of murdering noblemen and insecure husbands, dating back to fifteenth century France and beyond.

The tale of Bluebeard has an incredibly long and fascinating history. Unlike most fairy-tales, its origins can be traced to real events and people – horrific tales of murdering noblemen and insecure husbands, dating back to fifteenth century France and beyond. Some argue that its origins can be found even earlier, in the Roman myth of Cupid and Psyche or even the biblical story of Eve and her fatal curiosity. The story of Bluebeard is one full of deceit, death, murder, blood and forbidden chambers, and as with all great narrative traditions, it has been appropriated and adapted across generations and geographical location. With each re-telling, the cautionary legend is kept alive.

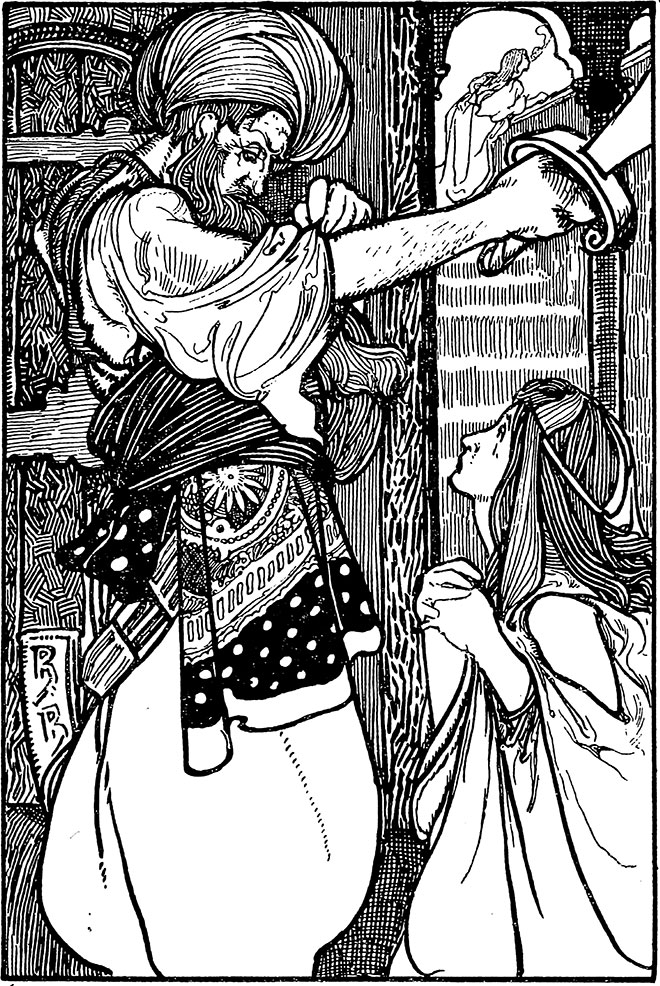

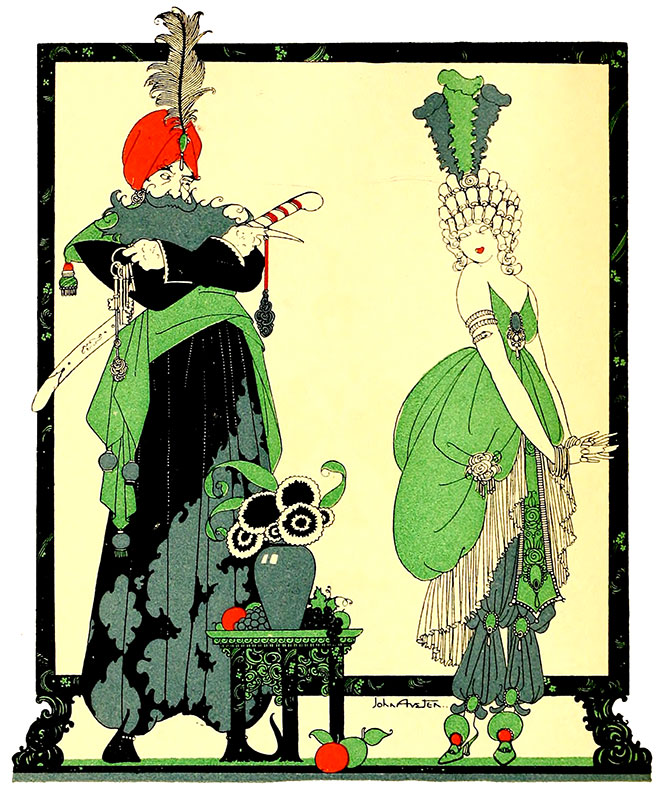

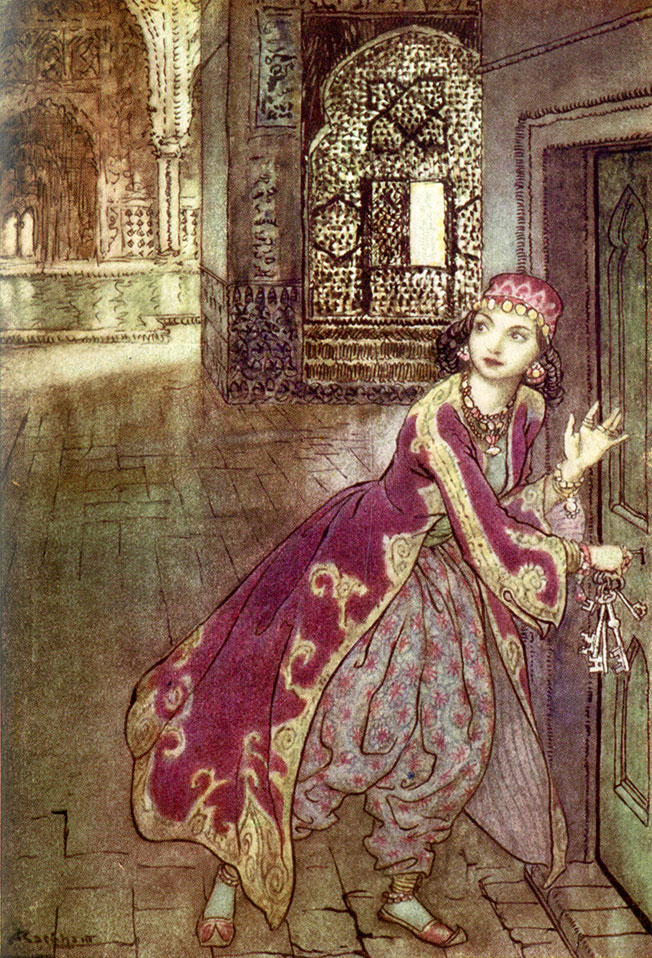

The version of the story that most modern readers will be familiar with, is that of the great French folklorist Charles Perrault, which tells the tale of a violent aristocrat in the habit of murdering his wives – and the attempts of one wife to avoid the fate of her predecessors. Published in 1697, in Histoires ou Contes du Temps Passeé, it is the least supernatural of Perrault’s tales, with no beasts, fairies or ogres; an enchanted key being the only magical object. In this particular version, Bluebeard himself is a wealthy aristocrat, feared and shunned because of his ugly blue beard (his unnatural hair giving a clue as to his extraordinary evil). He has been married several times, but no one knows what became of his wives. On marrying one of the three sisters, he leaves her in his château with all the keys, and instructions not to open a particular door. As soon as Bluebeard departs, the wife opens the door and discovers the floor awash with blood and the murdered bodies of her husband’s former wives hanging from hooks on the walls. Horrified, she drops the key into the pool of blood. Unable to get it clean, this reveals her betrayal to her husband, and the story’s macabre ending unfolds.

SELECTED BOOKS

Whilst this may sound a far-fetched chain of events, many scholars have pointed out the similarity of this tale with the legend of ‘Conomor the Accursed’, a sixth century Breton King. A Dominican Friar, Brother Albert Le Grand, recounts his villainy in the Life, Deeds, Death and Miracles of the Saints of Armorican Brittany (1636). In this book, we learn that Conomor had murdered his three previous wives. Tréphine, a good and just young woman, refuses to marry him because of his reputation, but when he threatens to invade her father’s lands she agrees. While Conomor is away from his castle, she finds a secret room containing relics of the deceased wives (just like Perrault’s narrative). Shocked, and praying for their souls – Tréphine is warned by the ghosts of the wives that Conomor will kill her if she becomes pregnant, since a prophecy states that he will be killed by his own son. Being pregnant, she runs away, but Conomor catches her and beheads her. In this tale, the young woman is rescued not by her brothers (as in Perrault’s), but by Saint Gildas who finds her, and miraculously restores her to life.

Despite these striking similarities, there is also another purported historical precedent; the legend of Gilles de Rais, a fifteenth century aristocrat and prolific serial killer, widely noted as a precursor of the Bluebeard narrative. Gilles de Rais (c. 1401 – 1440) was a French national hero, having served under Joan of Arc and helped to drive the invading English out of the country. Because of this, he became an incredibly rich and powerful man, living in relative isolation on his estates. Taking advantage of his power, he abducted local boys, thereafter sodomising and decapitating them. The remains of the fifty young men were subsequently discovered in his castle. It is thought that the story of Bluebeard consequently arose among the French peasantry, warning vulnerable young adults to stay away from the powerful aristocrats against whom they had no protection.

Whilst the account of Gilles de Rais’ crimes has fewer direct resemblances than the legend of Conomor, what all these stories have in common, is a caution against curiosity. The leading idea of the tale, of curiosity punished and prohibition infringed with evil results, is a widely utilized trope. The fatal effects of feminine curiosity have long been the subject of story and legend. Famous examples include the legend of Cupid and Psyche (Psyche disobeying the order to never gaze upon her husband, and later, overcome by ‘bold curiosity’ unable to resist opening the box (pyxix) of beauty); Pandora’s Box (an artifact in Greek mythology, originally a large jar given to Pandora, containing all the evils of the world); and the biblical story of Eve and the apple (again signifying the entry of sin and death into the world). The importance of the Adam and Eve parable is demonstrated in an illustrated version of Bluebeard by Walter Crane. When the wife is described as making her way towards the forbidden room, Crane depicts a tapestry showing the Serpent enticing Eve to eat the forbidden fruit. It is indeed an important forebear to the Bluebeard story, with God’s chastisement to Eve of particular relevance:

I will make your pains in childbearing very severe;

with painful labour you will give birth to children.

Your desire will be for your husband,

and he will rule over you.***

A competing theory of Bluebeard’s origins places the narrative in the genre of women’s tales (not as in the other interpretations, as a chastisement of female curiosity), told by mothers to their daughters. In this interpretation, it is a real-life cautionary account, of the practical consequences of childbirth. With yet more parallels to the legend of Conomor (and the demise of Tréphine), childbirth was the main cause of female mortality in Medieval Europe. Consequently, any marriage was potentially life-threatening for the woman, as with the act of becoming pregnant, death was ever-more likely. Here, one can link the narratives of curiosity punished (in the biblical telling, and in Perrault’s version) with an account not merely focused on a barbarous serial killer, but offering a dramatic rendition of everyday life.

In German Märchen, there are several close parallels with Bluebeard, for instance the Grimm’s Our Lady’s Child, where a virgin entrusts a little girl with the keys to thirteen doors, of which she may only open twelve. Behind each door was an apostle, and behind the thirteenth was the trinity, in a glory of flame. The girl’s finger became golden with the light (as Perrault’s key was dyed with blood) and she was thereafter banished from heaven. In Grimm’s Fitcher’s Bird, the resemblance is much closer however. A man carries off the eldest of three sisters to a magnificent house, leaving her with the keys and this time, an egg.

As usual, she is told not to open a certain door. Overcome with curiosity, she opens the door and drops the egg which refuses to be cleaned. This narrative is repeated with the second sister, and very nearly the third – who narrowly escapes the same fate and restores her sisters to life by reuniting their limbs. The Grimm’s resuscitation of the dead brides (although similar to the legend of Conomor, and the English variant Mr. Fox) is not repeated in Perrault’s telling. Indeed, it would have been highly inconvenient for Bluebeard’s surviving bride if the dead ladies were brought back to life – her legal position would have been ambiguous and she most likely would not have inherited his fortune.

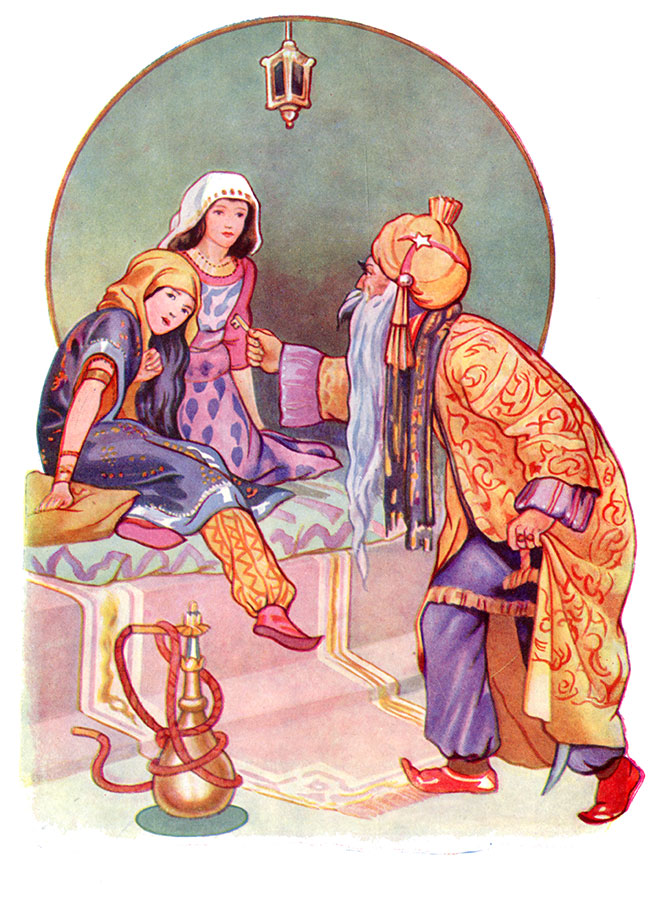

Hidden or forbidden chambers are relatively common in folkloric storytelling. For instance in Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone (published 1634 – 6), one tale tells of a Princess Marchetta entering a room forbidden by an ogress, and in another Italian variant, How the Devil Married Three Sisters, the devil is the wooer this time, and the closed door opens onto hell. How the Devil Married Three Sisters has a touch more humor than many of the other narratives though, as the devil – on seeing the resuscitated girls, is daunted by the idea of facing three wives and decamps. In one of the most interesting deviations, Prince Agib (in the Arabian Nights) is given a hundred keys to a hundred doors, but is forbidden from entering the door made of red gold. This is one of the few examples of the fatal act of curiosity being performed by a man, not a woman. In the story of Prince Agib, the motive is clear though: the forbidden door is a test. In La Barbe Bleue and Fitcher’s Bride however, the motive is less clear. It is not explained why Bluebeard would give a key to his wife that will reveal his horrific marital past. It is gaps in the story such as this, which have led some folklorists to postulate that an earlier, more complete telling of the story (although undiscovered), may have existed.

As a testament to this story’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, the story of Bluebeard continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. The tale has been translated into almost every language across the globe, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.