The History of the Arabian Nights – One Thousand and One Nights

Arabian Nights, more properly known as One Thousand and One Nights is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales, compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age.

Arabian Nights

Read Stories

The Origins of the Arabian Nights

Arabian Nights, more properly known as One Thousand and One Nights is a collection of Middle Eastern and South Asian stories and folk tales, compiled in Arabic during the Islamic Golden Age. This period lasted from the eighth century to the thirteenth century, when much of the Arabic-speaking world experienced a scientific, economic, and cultural flourishing – One Thousand and One Nights epitomising the rich and multifaceted literary output.

The title Arabian Nights came from the first English language edition (1706), which rendered the title as The Arabian Nights’ Entertainment. The work itself was collected over many centuries by various authors, translators, and scholars across West, Central, South Asia and North Africa. The tales are many and varied, but common throughout all the narratives is the initial frame story of the ruler Shahryār, and his wife Scheherazade….

One day, King Shahryār discovers that his wife has been unfaithful. Consequently, he has her executed. But in his bitterness and grief, he decides that all women are the same. Shahryār begins to marry a succession of virgins only to execute each one the next morning before she has a chance to dishonour him. Eventually, the vizier, whose duty it is to provide them, cannot find any more virgins. Scheherazade, the vizier’s daughter, offers herself as the next bride and her father reluctantly agrees. On the night of their marriage, Scheherazade begins to tell the King a tale but does not end it. The King, curious about how the story ends, is thus forced to postpone her execution in order to hear the conclusion. The next night, as soon as she finishes the tale, she begins (and only begins) a new one, and the King, eager to hear the conclusion, postpones her execution once again. So it goes on for 1,001 nights.

The Variety of Themes

The different versions have different, individually detailed endings. In some, Scheherazade asks for a pardon, in some, the King sees their children and decides not to execute his wife, in others, things happen that make the King distracted – but they all end with the king giving his wife a pardon and sparing her life. The One Thousand and One Nights and various tales within it make use of many innovative literary techniques, which the storytellers of the tales rely on for increased drama and suspense. It is one of the earliest examples of ’embedded narratives’ – which can be traced back to earlier Persian and Indian storytelling traditions, most notably the Panchatantra (an ancient Indian collection of interrelated animal fables in verse and prose).

Across the collection, the tales vary extremely widely. They include historical tales, love stories, tragedies, comedies, poems, burlesques, and various forms of erotica. Numerous stories depict ghouls, apes, sorcerers, magicians, and legendary places, which are often intermingled with real people and geography. The narrator’s standards for what constitutes a cliff-hanger seem broader than in modern literature. While in many cases a story is cut off with the hero in danger of losing his life or another kind of deep trouble, in some parts, Scheherazade stops her narration in the middle of an exposition of abstract philosophical principles or complex points of Islamic philosophy, and in one case during a detailed description of human anatomy according to Galen. In all these cases, she is justified in her belief that the King’s curiosity about the sequel would buy her another day of life. Some of the stories widely associated with The Nights, in particular ‘Aladdin’s Wonderful Lamp‘, ‘Ali Baba and the Forty Thieves’, and ‘The Seven Voyages of Sinbad the Sailor‘, while almost certainly genuine Middle-Eastern folk tales, were not part of The Nights in its original Arabic versions, but were added to the collection by Antoine Galland (1646 – 1715) and other European translators.

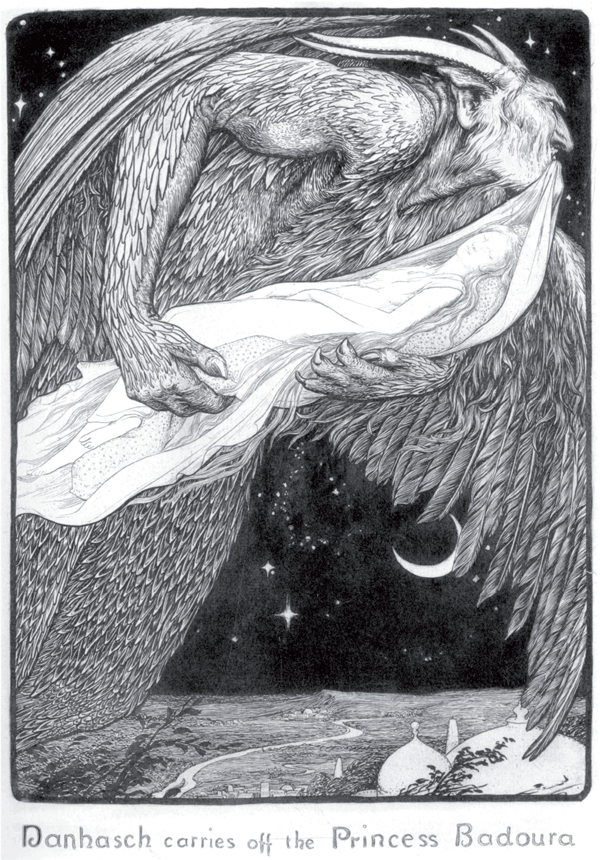

Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights – Illustration by John D. Batten

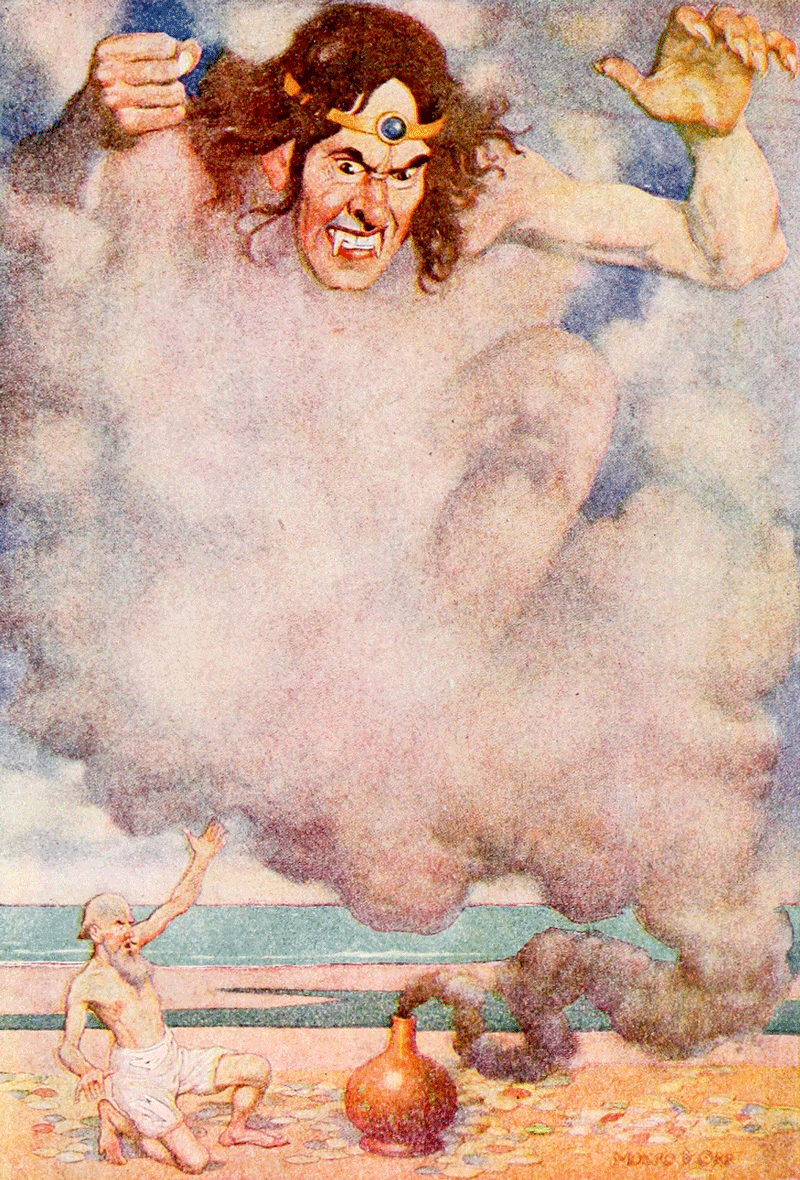

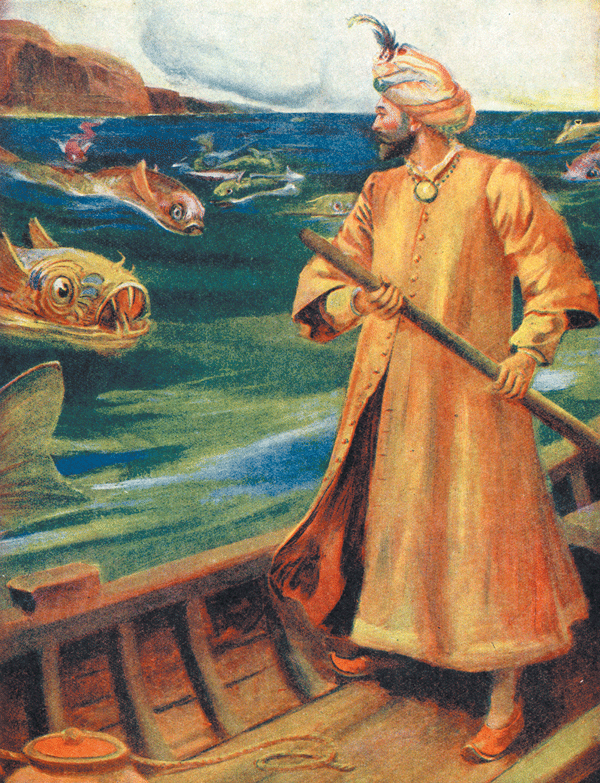

The story of the Fisherman and the Genie – The Arabian Nights illustrated by Monro S. Orr

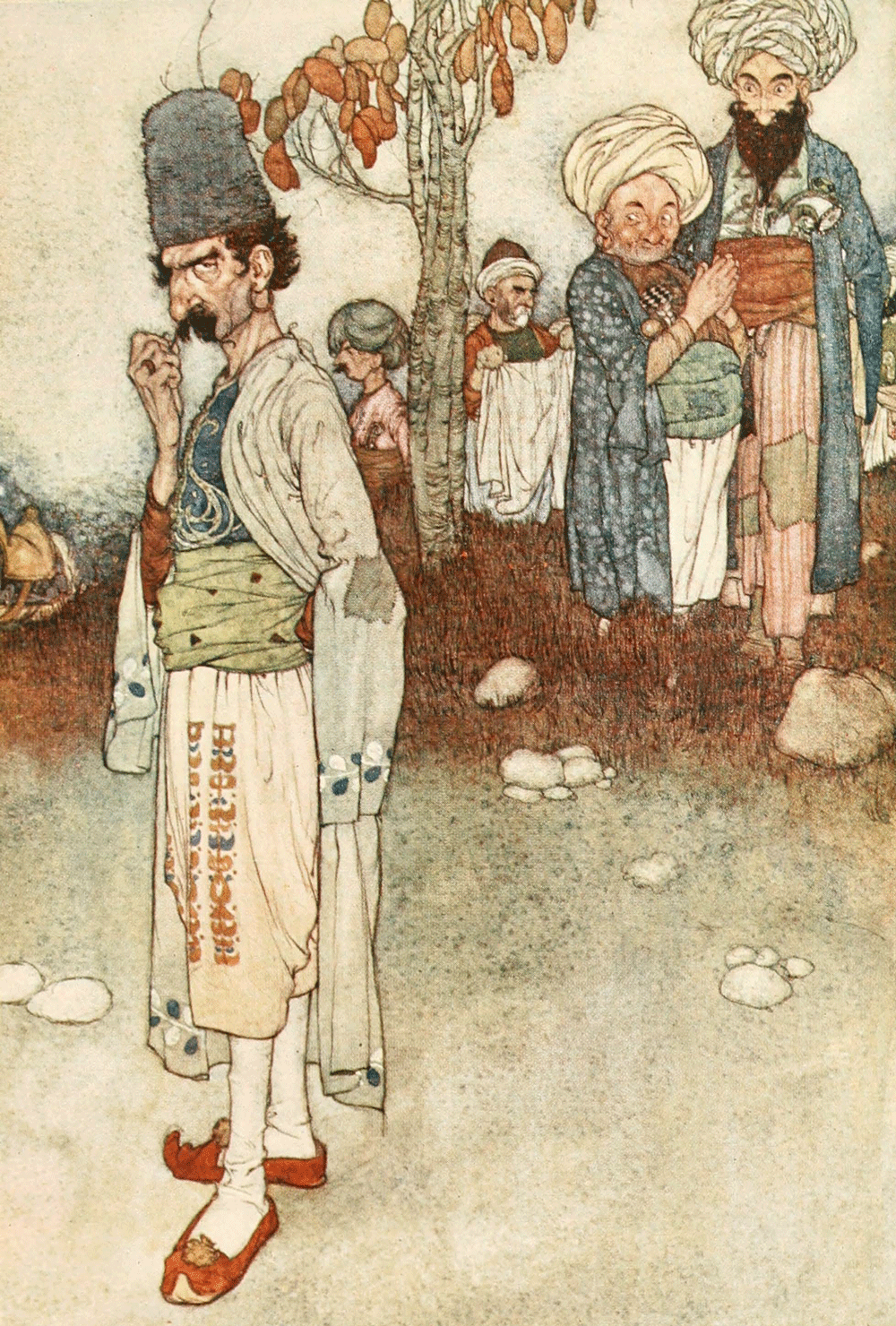

Stories from the Arabian Nights – Illustrated by Edmund Dulac

The History of the Arabian Nights Stories

The history of the Nights is extremely complex, and modern scholars have made many attempts to untangle the story of how the collection came about. Most scholars agree that is was a composite work, coming from India and Persia. At some time (probably in the early eighth century), these tales were translated into Arabic under the title Alf Layla, or ‘The Thousand Nights’. The original core of stories was probably quite small, with Arabic stories added to it in the 9th and 10th centuries. Previously independent sagas and story cycles may have been added later, as the tales moved through Syria and Egypt – many showing a preoccupation with sex, magic or low life.

The first European version (1704 – 1717) was translated into French by Antoine Galland, from an Arabic text of the Syrian recension. This twelve-volume work, Les Mille et une nuits, contes arabes traduits en français (‘Thousand and one Nights, Arab stories translated into French’), included many stories that were not in the original Arabic manuscript. He wrote that he heard them from a Syrian Christian storyteller from Aleppo and a Maronite scholar whom he called ‘Hanna Diab’. The text was an immediate best-seller throughout Europe, and numerous other translations soon appeared.

As scholars were looking for the presumed ‘complete’ and ‘original’ form of the Nights, they naturally turned to the more voluminous texts of the Egyptian recension, which soon came to be viewed as the ‘standard version’. The first translations of this kind, such as that of Edward Lane (1840, 1859), were bowdlerised. Unabridged and unexpurgated translations were made, first by John Payne, under the title The Book of the Thousand Nights and One Night (1882, nine volumes), and then by Sir Richard Francis Burton, entitled The Book of the Thousand Nights and a Night (1885, ten volumes). In view of the sexual imagery in the source texts (which Burton even emphasised further, especially by adding extensive footnotes and appendices on Oriental sexual mores) and the strict Victorian laws on obscene material, both of these translations were printed as private editions for subscribers only, rather than published in the usual manner.

Illustrated Editions

With such scandalous and ingenious subject matter – Arabian Nights has captured the imagination of many great artists. Famous illustrators of the British editions include John Tenniel and John Everett Millais for Dalziel’s Illustrated Arabian Nights Entertainments, published in 1865; Walter Crane for Aladdin’s Picture Book (1876); Albert Letchford for the 1897 edition of Burton’s translation; Edmund Dulac for Stories from the Arabian Nights (1907), Princess Badoura (1913) and Sindbad the Sailor & Other Tales from the Arabian Nights (1914). Others artists include John D. Batten, (Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights, 1893), Kay Nielsen, Maxfield Parrish, and W. Heath Robinson.

***

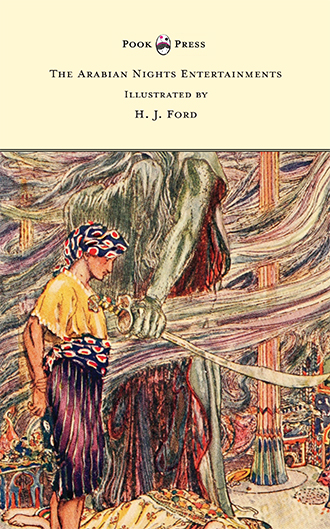

Pook Press books featuring tales of the Arabian Nights:

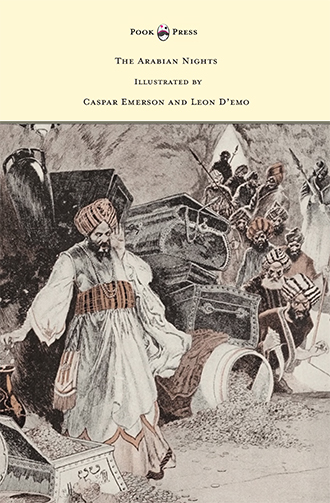

The Illustrated Arabian Nights – By Caspar Emerson and Leon D’emo

Fairy Tales From The Arabian Nights – Illustrated by John D. Batten

Bluebeard – And Other Mysterious Men with Even Stranger Facial Hair (Origins of Fairy Tales from Around the World)

The Big Book of Fairy Tales – Illustrated by Charles Robinson

The Arthur Rackham Fairy Book – A Book of Old Favourites with New Illustrations

Further Featured Books

1 Comment

Miss Carter and the Ifrit – The Book Trunk

2nd March 2020[…] like this, and I love his red shoes and the turban with it’s curved feather. I found it at Pook Press, which is a lovely […]