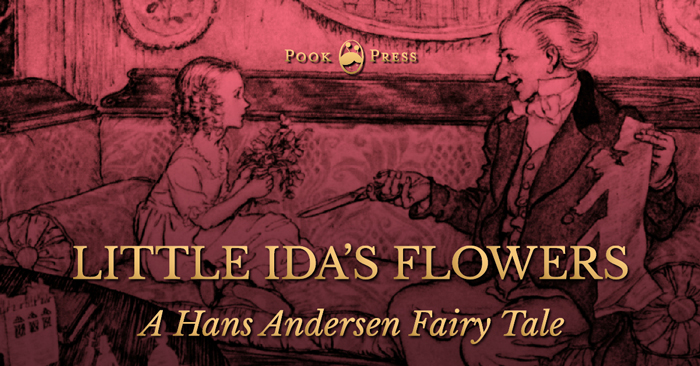

Little Ida’s Flowers- A Hans Andersen Fairy Tale

A little wax doll, a palace full of flowers, and a midnight dance.

Little Ida’s Flowers

– A Hans Andersen Fairy Tale –

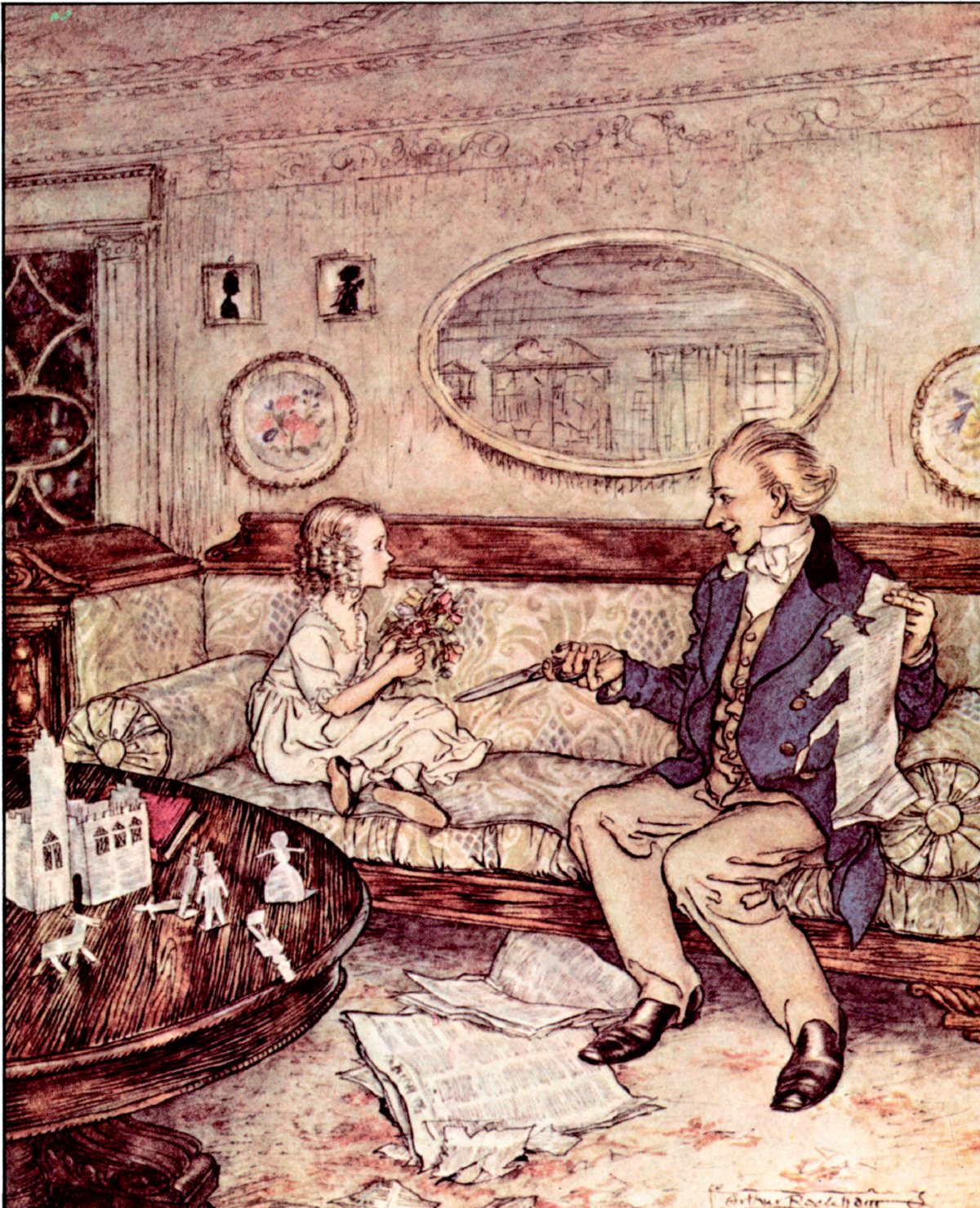

“My Poor flowers are quite withered,” little Ida said. “They were so beautiful yesterday evening, and now the leaves are all dead. What is the reason?” she asked the student, who was sitting on the sofa; for she was very fond of him, as he told her all manner of pretty stories and cut out the most amusing pictures for her—hearts with little ladies dancing inside; flowers, and castles of which the doors opened. He was a lively young man. “Why do the flowers look so wretched to-day?” she asked again, showing him a nosegay, which was quite dead.

“Why, don’t you know what’s the matter with them?” the student said. “The flowers were at a ball last night, and that’s why they hang their heads.”

“But how can that be, for the flowers cannot dance,” little Ida said.

“And why not?” the student answered. “As soon as it gets dark, and we are all asleep, they jump about merrily enough; almost every night they have a dance.”

“Are there no children at the balls?”

“Oh yes,” the student said; “there are quite little daisies and may-blossoms.”

“And where do the most beautiful flowers dance?” little Ida asked.

“Have you not often been outside the city gates, to the palace, where the King lives in summer, and where there is the beautiful garden with such quantities of flowers? You know the swans which swim up to you when you feed them with bread crumbs. Depend upon it, there are large balls there.”

“I was in the garden yesterday with my mother,” Ida said; “but all the leaves were off the trees, and there were no flowers whatever. Where are they all? In summer I saw such quantities.”

“They are inside the palace,” the student said. “You must know that as soon as the King and all the courtiers move into the town, the flowers run off at once out of the garden into the palace, and there make merry. You should see that. The two most beautiful of the roses seat themselves upon the throne, and they are then king and queen. The red cockscombs stand bowing on either side, and they are the pages. Then come the prettiest flowers, which represent the maids of honour, and there is a grand ball. The blue violets are midshipmen, and they dance with hyacinths and crocuses, whom they call milady. The tulips and the great tiger lilies are old ladies who watch that the dancing is good, and that all goes on with propriety.”

“And does no one interfere with the flowers going into the palace?” little Ida asked.

“No one knows really anything about it,” the student said. “It’s true that sometimes the old steward, who has to see that all is right, comes in of an evening; but no sooner do the flowers hear the jingling of his big bunch of keys than they are quite quiet, and hide themselves behind the curtains. ‘I smell that there are flowers here,’ he says; but he cannot see them.”

“Oh, what fun that is!” little Ida said, clapping her hands. “And should I not be able to see the flowers either?”

“Yes,” the student answered; “and remember, the next time you go out there, that you look through the window, and you will see them plainly enough. I did so to-day, and there lay a long yellow lily stretched upon the sofa. That was one of the ladies-in-waiting.”

“And are the flowers from the botanical garden there? Can they get as far?”

“To be sure they can,” the student answered; “for, if necessary, they can fly. Have you not noticed many beautiful butterflies—red, yellow, and white—that look almost like flowers, which indeed they have been? They have broken off from their stems, flying up in the air, beating about with their leaves as if they were wings; and as they behaved well, they received permission to fly about, and not be obliged to sit quietly fastened down to their stems, till at length the leaves became real wings. All this you may have seen yourself. However, it may be that the flowers from the botanical garden have never been in the King’s palace, or even that they do not know what sport goes on there at nights. And now I’ll tell you something—how you can astonish the professor of botany who lives here close by. You know him, do you not? When next you go into his garden, you must tell one of the flowers that there is dancing at the palace every night. That one will tell the others, and away they’ll fly. Then when the professor goes into the garden, he will not find a single flower, and he will be nicely puzzled to think what has become of them all.”

“But how can the flower tell the others?—for flowers cannot speak.”

“That is true enough,” the student said; “but then they make signs. Have you not often noticed that when the wind blows a little the flowers bend down, and all the green leaves move? That is as plain as if they spoke.”

“And can the professor understand them?”

“Certainly he can. One morning he went into the garden and saw a stinging nettle making signs to a red carnation, which signs meant, ‘You are very pretty, and I love you. Now the professor cannot bear anything of that sort, so he gave the stinging nettle a slap on its leaves—for these are its fingers; but he stung himself, and since then he has not ventured to touch a stinging nettle.”

“Oh, what fun!” little Ida said, and laughed out loud.

“How can any one talk such nonsense to a child!” the tedious chancery counsellor said, who, having called to pay a visit, was sitting on the sofa. He did not much like the student, and always began to growl when he saw him cutting out the funny pictures—first, it was a man hanging on the gallows with a heart in his hand, for he was a robber of hearts; and then an old witch riding on a broom, and carrying her husband on her nose. That sort of thing annoyed the counsellor, and he would then say, “How can any one put such foolish notions into a child’s head!”

But what the student told little Ida about her flowers appeared very funny to her, and she thought much of it. The flowers hung their heads, because they were tired after dancing all the night, and no doubt they felt ill. Then she carried them to her other playthings, which were on a nice little table, the drawer of which also was full of pretty things. In the doll’s bed lay the doll Sophy, sleeping; but little Ida said to her, “You must really get up, Sophy, and be satisfied with passing this night in the drawer, for the poor flowers are ill, and must sleep in your bed, which will perhaps put them right again.” She then took the doll out of its bed; and it looked quite fretful, but did not say a word, for it was sulky at having to give up its bed.

Ida laid the flowers in the doll’s bed, and covering them up with the clothes, said they must lie quite quiet, and she would make them some tea, so that they might be quite well by the following day and be able to get up. She then drew the curtains of the little bed, that the sun might not shine in their eyes.

The whole evening she could not help thinking of what the student had told her; and when it was time for her to go to bed, she must needs first look under the curtain that hung at the window, where her mother’s beautiful flowers—hyacinths as well as tulips—stood, and she whispered quite low, “I know that you are going to the ball to-night.” But the flowers pretended not to understand her, and did not move a leaf; however, little Ida knew what she knew, for all that.

When she was in bed she lay awake a long time thinking how pretty it must be to see all the beautiful flowers dancing in the King’s palace. “I wonder whether my flowers were really there?” She then went to sleep, but woke again in the night, having dreamed of the flowers, the student, and the chancery counsellor who said he was putting foolish fancies into her head. All was quiet in the bedroom where Ida lay; the night-lamp burned on the table, and her father and mother were asleep.

“I wonder whether my flowers are still lying in Sophy’s bed,” she thought. “I should much like to know.” She raised herself up a little in the bed and looked towards the door, which stood ajar. In the next room lay her flowers and all her playthings; and as she listened, it seemed to her as if she heard the piano being played, but quite softly and more beautifully than she had ever heard before.

“No doubt all the flowers are now dancing in there,” she said. “Oh dear! how much I should like to see them!” But she could not venture to get up for fear of waking her father or mother.

“If they would but come in here,” she said. But the flowers did not come in, and as the music continued playing she could resist no longer, for it was much too pretty; so she crept out of her little bed gently to the door and looked into the next room. Oh, how beautiful it was—what she there saw!

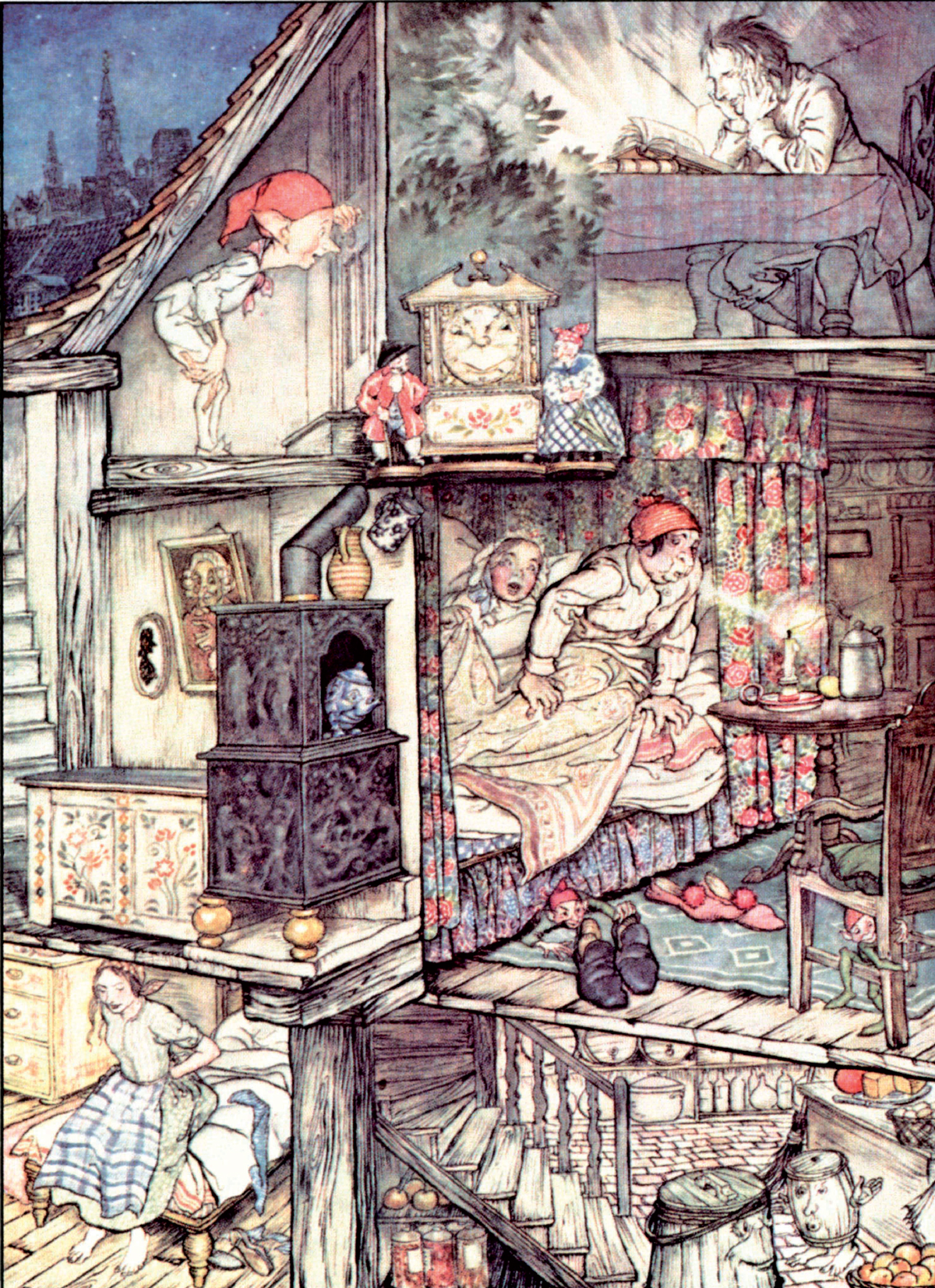

There was no night-lamp burning; but yet it was quite light, for the moon was shining through the window right into the middle of the room, and it was almost like day. All the hyacinths and tulips stood in two rows along the room, so that there were none left in the window. The flower pot stood there empty, whilst the flowers were dancing so prettily on the floor of the room, round each other, forming a regular ladies’ chain, and holding each other by the long green leaves as they whirled round. At the piano sat a large yellow lily, which Ida must certainly have seen during the summer, for she remembered quite well that the student had said, “How exactly it is like Miss Line!” Every one laughed at him then; but it really seemed to little Ida now that the long tall yellow flower was indeed like that young lady, and it had the same ways too at the piano. Now it leaned its long yellow face to one side, now to the other, whilst it nodded the time to the beautiful music. Little Ida was not noticed, and she now saw a large blue crocus jump on to the table on which the playthings were, go straight up to the doll’s bed and draw the curtains. There lay the sick flowers; but they got up at once, and nodded to the others, as much as to say that they would dance too. The old shepherd, who had lost his underlip, stood up and bowed to the beautiful flowers, which did not appear at all sick now, for they jumped down to join the others, and were as merry as possible.

It sounded as if something fell, and when Ida looked round she saw that it was the little three-legged stool that had jumped down from the table—seeming to think it belonged to the flowers. It was a neat little stool, and on it there sat a little wax doll, with just such another broad-brimmed hat on its head as the chancery counsellor was in the habit of wearing. The stool hopped about on its three legs, stamping heavily; for it was dancing the Mazurka, which the flowers could not dance, for they were too light to stamp.

The wax doll on the stool became all at once quite big, and cried out, “How can any one talk such nonsense to a child!” and then it was exactly like the counsellor, looking quite as yellow and fretful. Then it became a little wax doll again, and all this was so droll that Ida could not restrain her laughter. The three-legged stool continued to dance, and the chancery counsellor had to dance with it, whether he would or not, whether he made himself big, or remained the little wax doll with the large black hat. There was now a knocking in the drawer, where Ida’s doll Sophy was lying with other playthings; and the old shepherd, jumping on to the table, lay flat down, and crept as near as possible to the edge, when he was able to pull the drawer out a little. Then Sophy got up and looked around her, quite astonished. “Why, here is a dance!” she said. “Why did no one tell me that?”

“Will you dance with me?” the shepherd said.

“Oh yes; you are a pretty fellow to dance,” she said, and turned her back upon him. She then seated herself upon the table, expecting that one of the flowers would come and engage her; but none came, and then she coughed, “Hem, hem, hem!” But none came, for all that. The shepherd danced all by himself, and not so badly either.

Now, as not one of the flowers appeared to see Sophy, she let herself fall from the table on to the floor with a great noise, which brought all the flowers about her, and they asked her whether she had not hurt herself. They were all so kind and polite to her—particularly those that had lain in her bed. But she had not hurt herself at all, and Ida’s flowers thanked her for the beautiful bed; were very attentive to her; and, leading her into the middle of the room, where the moon shone, they danced with her. Sophy was delighted, and said they might keep her bed, for she did not at all mind sleeping in the drawer.

But the flowers said, “We thank you from our hearts, but we cannot live so long, for to-morrow we shall be quite dead. Then tell little Ida to bury us where the canary lies, and we shall grow again next summer, when we shall be more beautiful than now.”

“No, you must not die,” Sophy said, kissing them; and just then a quantity of the most beautiful flowers came dancing in through the door. Ida could not at all imagine where they came from, unless from the King’s palace. In front were two beautiful roses, wearing little crowns of gold; these were king and queen. Then followed the prettiest gilliflowers and pinks, bowing on all sides. They had music of their own, large poppies and peonies blowing away on pea-shells till they were quite red in the face. The snowdrops and bluebells were ringing, exactly as if they had metal bells, so that altogether it was most extraordinary music. Then came quantities of other flowers—the blue violets and the red amaranths, daisies and mayflowers—and all danced together, and kissed each other, so that it was delightful to look at them.

At length all the flowers wished each other good night, and then little Ida crept back to her bed, where she dreamed of all she had seen.

As soon as she got up the next morning she went to the little table to see whether the flowers were still there. She drew aside the curtains of the little bed; yes, there they lay, but quite withered, a great deal more so than the day before. Sophy was lying in the drawer where she had laid her, and she looked very sleepy.

“Do you remember what you were to tell me?” Ida asked; but Sophy looked quite stupid, and did not answer one single word.

“You are not at all good,” Ida said—“when all of them danced with you too.” She then took a little paper box, on which the most beautiful birds were painted, and having opened it, laid the dead flowers in it. “That shall be your pretty coffin,” she said; “and when my cousins come they shall help me to bury you in the garden, so that you may grow again next summer and be more beautiful than ever.”

The two cousins were two lively boys, whose names were John and Adolphus. Their father had given each of them a cross-bow, which they had brought with them to show Ida. She told them of the poor flowers which had died the day before and invited them to be present at the funeral. The two boys walked on in front, with their crossbows on their shoulders, and little Ida followed with the dead flowers in the pretty box. They dug a small grave in the garden, and Ida, having first kissed the flowers, placed them with the box in the earth, and the cousins fired their crossbows over the grave, for they had neither guns nor cannon.

* * * * *

This story was taken from the book:

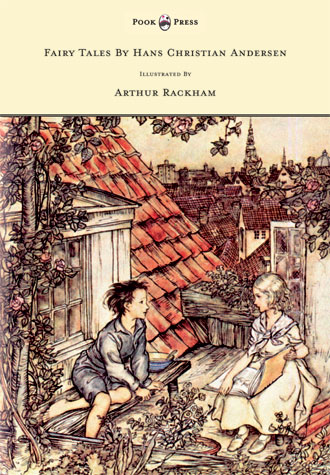

Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen – Illustrated by Arthur Rackham

This collection, Fairy Tales by Hans Christian Andersen was originally published in 1932. It contains many of Hans Christian’s best-loved tales, and is illustrated by the charming colour plates and black and white drawings of Arthur Rackham. The stories include: ‘The Ugly Duckling’, ‘The Snow Queen’, ‘The Steadfast Tin Soldier’, ‘The Emperor’s New Clothes’, ‘Thumbelina’, ‘The Princess and the Pea’, ‘The Little Match Girl’, ‘The Little Mermaid’, and many more.

Other storybooks you might like: