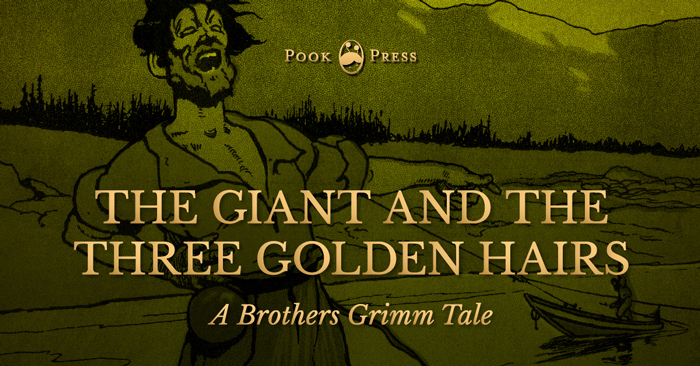

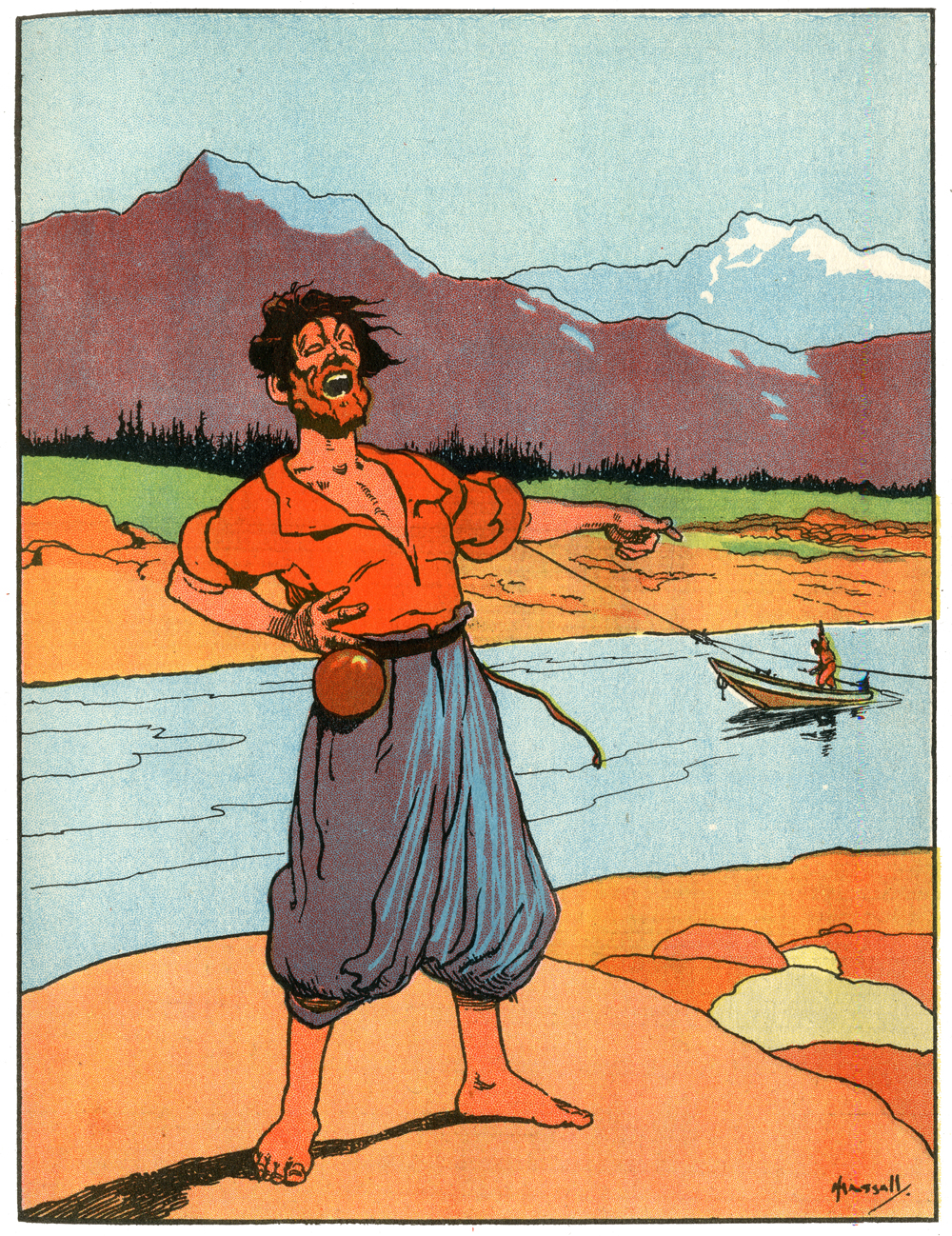

The Giant and Three Golden Hairs – A Brothers Grimm Tale

A lucky little baby, a giant with hair of gold, and a crafty ferryman.

The Giant and The Three Golden Hairs

– A Brothers Grimm Tale –

THERE was once a poor woman whose little baby son was born lucky, for it had been said of him that when he grew to be fourteen years of age, he would marry the King’s daughter.

It happened that the King came to the village where the luck-child was, but no one knew that it was the King, so that when he asked for news they told him of the lucky little baby which had been born that very day, and of whom it was said that he would marry the King’s daughter when he was fourteen years of age.

Now, the King, who had a bad heart, was very angry when he heard this. He went to the parents and offered them a large amount of money for their boy. “Well,” thought they, “he is born lucky, so nothing can go amiss with him,” and so they gave him to the King, who placed him in a box and rode on until he came to a deep river, into which he threw the box, thinking, “There, I have freed my daughter from an unlooked-for suitor.”

The box, however, did not sink, but floated like a little boat, until it came within two miles of the King’s capital, when it was caught and held fast in a mill-wheel.

The miller’s boy saw it, and drew it ashore with a hook, thinking that he had found a great treasure. But when he opened the box, there lay a pretty, smiling, healthy little baby boy. He carried him to the miller and his wife, and, as they had no children of their own, they were only too glad to take the little foundling in and care for him, and they trained him so well that he grew up a kind-hearted, honest lad.

One day the King was out, when a terrible thunderstorm came on, so he went to the mill for shelter. Whilst there he saw a tall, handsome lad, and asked the miller and his wife if he were their son.

“No,” they answered, “he was a foundling. Fourteen years before, he had come sailing down the mill-stream in a box, and the mill-boy had pulled him out of the water.”

The Giant and the Three Golden Hairs illustration by Helen Stratton

Then the King knew that he was the luck-child whom he had thrown into the water, and he said, “Will you let the boy take a letter to the Queen for me, good people, and I will give him two golden guineas as a reward?”

“The King has only to command,” they answered, and, calling the boy, they bade him get ready to go.

Then the King wrote a letter to the Queen, in which he said:—“As soon as the boy who brings this arrives, he is to be killed and buried. See that this is done before my return.”

The boy set out with the letter, but he lost his way, and when night came on he found himself in the middle of a thick wood. He saw a light glimmering through the darkness, and went towards it until he came to a cottage. He entered, and found an old woman sitting alone beside the fire. She started when she saw the boy, and asked him where he came from and whither he was going.

“I come from the mill,” he answered, “and I am carrying a letter to the Queen, but I lost my way in the wood, and I should be glad to stay the night with you if you will let me?”

“This is a robbers’ house, my poor boy,” said the old woman, “and when they come home they will kill you.”

“Let them come,” answered the boy; “I am not afraid, but I am too tired to go farther.” And with that he stretched himself upon a bench and went to sleep. Soon afterwards the robbers came home and asked angrily who the strange boy was. When the old woman told them, they opened the letter and read it, and then even their hard hearts were touched. So the captain of the band tore up the letter and wrote another in its stead, in which he said that when the boy arrived he was to be married immediately to the King’s daughter. They allowed him to sleep peacefully until the morning, and when he awoke gave him the letter and showed him the right way. When the Queen had received the letter, she read it, and then ordered a magnificent marriage feast to be prepared, and the King’s daughter was married to the luck-child, and as he was both handsome and well-mannered, the Princess was very well content.

After a little time the King came home, and saw that the prophecy was fulfilled, and the luck-child married to his daughter. “How did it happen?” he asked his wife, “for I gave you very different orders in my letter.”

The Queen gave him the letter, saying that he might see for himself what was written in it. When the King had read it, of course he knew that it had been changed, and he asked the boy where he had been with the letter, and why he had brought another instead of it.

“I know nothing about it,” the boy replied; “it must have been changed in the night when I was asleep in the cottage in the wood.”

“You shall not find things quite so easy as you suppose,” the King said angrily. “Whoever marries my daughter must fetch me three golden hairs from the head of the fiery giant. If you can do this you shall have the Princess.”

The Giant and the Three Golden Hairs Illustration by Anne Anderson

The King hoped that he would now be rid of the young man, but the luck-child answered, “You shall have the golden hairs; I am not afraid of the fiery giant.”

Then he took leave of them and set out upon his travels. His way led him through a large town, at the gates of which he was stopped by a watchman, who asked him what trade he had learnt and how much he knew. “I know everything,” replied the luck-child.

“Then you will do us a great favour,” said the watchman, “if you will tell us how it is that the fountain in the market-place, which once flowed with wine, has suddenly run dry, and does not even supply us with water.”

“You shall certainly know,” replied the luck-child, “if you will wait for an answer until I come back.”

Then he went on his way, until he came to another large town, where the watchman again asked him what his trade was and how much he knew. “I know everything,” he replied.

“Then you can do us a favour,” said the watchman. “Will you tell us why a certain tree in our town, which has always borne golden apples, does not bring forth so much as a leaf nowadays?”

“You shall certainly know,” replied the luck-child, “if you will wait for an answer until I come back.”

Then he went on again, until he came to a wide river which he had to cross. The ferryman asked him what his trade was and how much he knew. “I know everything,” he answered.

“Then you can do me a favour,” said the ferryman, “and tell me why I am bound to remain here for ever, ferrying people backwards and forwards across the stream, and can never free myself.”

“You shall certainly know,” said the luck-child, “if you will wait for an answer until I come back.”

When he had crossed the river the young man found himself close to the fiery giant’s home; inside it looked all black and sooty, but the fiery giant was not at home, though his grandmother was sitting there in a big arm-chair.

“What do you want?” she asked, and she did not look half as wicked as one would have expected the grandmother of a fiery giant to look.

“I should like three golden hairs from the giant’s head,” he answered. “Unless I can get them I shall lose my wife.”

“That is a good deal to expect,” said she, “for if he comes home and finds you, he will certainly kill you. However, I am sorry for you, so I will see what I can do to help you.”

Then she changed him into an ant, and told him to creep into the folds of her dress, where he would be safe.

“So far, so good,” said he, “but there are three things I should dearly like to know, namely:—Why a certain fountain which once flowed with wine has now become dry, and does not even spout forth water? Why a certain tree, which once bore golden apples, now does not so much as put forth a single leaf? And why the ferryman at the river must ferry people backwards and forwards for ever and ever, without being able to free himself?”

“Those are difficult questions,” said she, “but keep still and listen attentively to what the giant says when I pull out the three golden hairs.”

In the evening the fiery giant came home. No sooner had he entered than he noticed a difference in the air. “I can smell human flesh,” said he. “There is something wrong here.”

He searched in every hole and corner, and yet could find nothing. His grandmother scolded him roundly all the time. “I have only just swept up and put everything tidy,” said she, “and now you go and upset the place again. You are always fancying you smell human flesh. Sit down and eat your supper, do!”

When he had eaten his supper he felt tired, so he laid his head in his grandmother’s lap, and was soon fast asleep and snoring. Then the old woman seized a golden hair, plucked it out and laid it beside her.

“Oh! oh!” screamed the giant. “What are you doing?”

“I had a bad dream,” answered the grandmother, “and in my fright I pulled your hair.”

“What did you dream?” asked the giant.

“I dreamt of a fountain in a market-place which had once flowed with wine, but which was sealed up so that not even a drop of water came from it. What could have caused such a thing?”

“Why, if only the folk knew it,” laughed the giant, “there is a toad sitting beneath a stone in the fountain, and if that were killed the wine would flow as before.”

The grandmother stroked his head gently until he fell asleep again, and snored so that the windows shook. Then she pulled out the second hair. “Oh! oh! what are you doing?” cried the giant angrily.

“Don’t be cross,” said she, “I was dreaming when I did it!”

“What did you dream this time?” he asked.

“I dreamt,” said she, “that in a certain kingdom there was a tree which had once borne golden apples, but which now did not bring forth so much as a single leaf. Now, what could be the reason of such a thing?”

“Ha! ha!” laughed the giant. “If the people only knew, there is a mouse gnawing at the root of the tree. If it were killed the tree would soon bear golden apples again, but if the mouse gnaws on much longer it will wither and die. But there, let me hear no more of your dreams, and if you disturb my sleep again I will give you a good sound box on the ear.”

The grandmother soothed him with gentle words, and stroked his head softly until he fell asleep again. Then she seized the third golden hair and pulled it out. The giant sprang up with a yell, and would have treated her badly had she not managed to calm him.

“Who can help bad dreams?” said she.

“Whatever did you dream?” he asked curiously.

“I dreamt of a ferryman,” she answered, “who was bemoaning his hard fate, for he was forced to ferry people backwards and forwards across a stream, and no one came to release him.”

“Ah!” said the giant, “he is a silly, and no mistake. If anyone comes to be ferried across, he has but to place the oar in his hand and he will be free, whilst the new-comer will be compelled to take his place.”

“You shall have the golden hairs; I am not afraid of the fiery giant.”

Now that the grandmother had pulled out the three golden hairs and the giant had answered the three questions, she let him sleep on undisturbed until the morning. As soon as the giant had gone out the old woman took the ant from the fold of her dress, and changed it back into the form of the luck-child again.

“There are the three golden hairs,” said she; “the answers to your three questions you will have heard for yourself.”

The young man thanked the old woman, and went his way. When he came to the ferryman he was asked for the promised answer.

“First ferry me across,” said the luck-child, and when he had reached the opposite bank he gave him the giant’s advice: “The next time anyone comes to be ferried across the stream, place the oar in his hand.”

Then he went on to the down where the unfruitful tree stood, and where the watchman was waiting for an answer, and he said, just as he had heard the giant say: “Kill the mouse which is gnawing at the root, and the tree will once more bear golden apples.”

The watchman thanked him, and gave him two asses laden with gold, which were driven after him. At last he came to the town in which was the sealed fountain, and said to the watchman: “Beneath a stone in the fountain sits a toad—find it and kill it, and at once the fountain will yield wine in abundance, as in days gone by.”

The watchman thanked him, and also gave him two asses laden with gold.

At length the luck-child reached home safely, and was welcomed lovingly by his wife, who was delighted to hear how fortunate he had been. He gave the King what he had asked for—namely, the giant’s three golden hairs, and when the greedy man saw the four asses laden with gold he was very well pleased, and told the young man that, as he had fulfilled the conditions, he might have his daughter.

“But, my dear son-in-law,” said he, “wherever did you get so much gold? Why, there is untold wealth there!”

“I crossed a river,” answered the young man, “where gold strews the shores instead of sand, so I brought some away with me.”

“Could I get some too?” asked the King eagerly.

“As much as you please,” answered the luck-child. “There is a ferryman by the river who will row you across, and then you can fill every sack you have.”

The grasping King set out upon the way with all speed, and when he came to the river he beckoned to the ferryman to come and take him over. The ferryman came and bade him step into the boat, but when he had ferried the King across to the other side he put the oar into his hand, and ran away. And from that time the King was condemned, on account of his great wickedness, to ferry the boat to and fro.

“And is he there still?” you ask.

Perhaps, but who knows? If he is, you may be sure it is because no one will take the oar from him.

This story was taken from the book:

Popular Nursery Stories – Illustrated by John Hassall

This book, Popular Nursery Stories – Illustrated by John Hassall is a fantastic collection of stories from the well-known authors the Brothers Grimm and Hans Christian Andersen. They are decorated with John Hassall’s bold and charming black and white line drawing and colour plates.