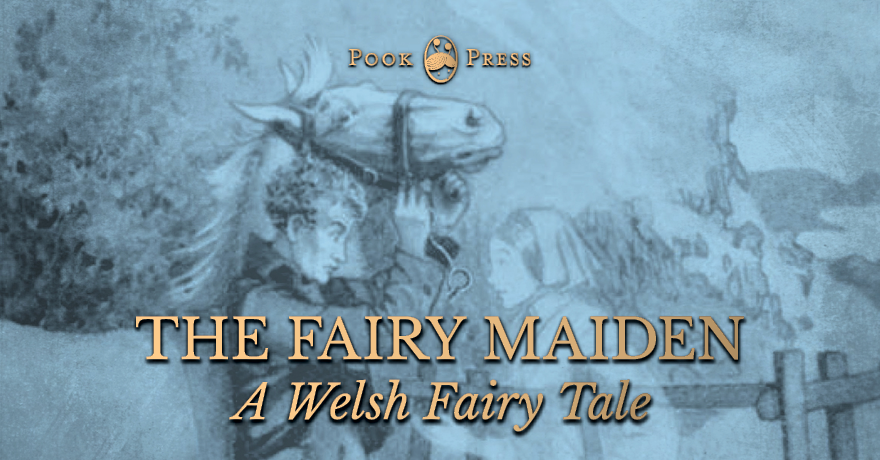

The Fairy Maiden – A Legendary Tale from Wales

This classic Welsh fairy tale, The Fairy Maiden, tells the tale of a Welsh boy named Tom who, while travelling back to his home near Snowdon, happens upon a circle of dancing folk. Overcome with affection for one of the dancers, Tom steals her away from the crowd.

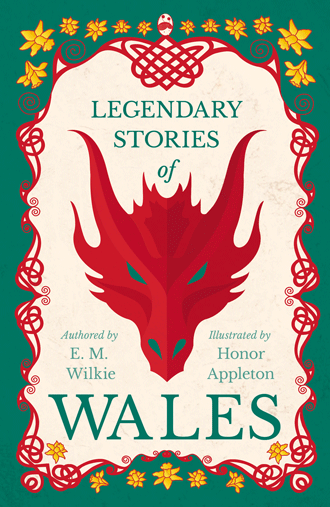

You can find this story, along with many other Welsh legends and folk tales in the gorgeous book Legendary Stories of Wales – Illustrated by Honor Appleton.

The preface of this book states “The Welsh have always liked to hear and to tell of strange happenings, and many Welsh people have lively imaginations, so you may expect to hear of folk who were bewitched, of folk who met the fairies, of folk who found wonders even in friendly woods and fields.” That is exactly what you will find in this magical story.

The Fairy Maiden

A Legendary Tale from Wales

This is a tale of the still, hot days in summer when the dust lies thick and soft on the roads, and muffles the footfall of horse and man, and powders the hedge-plants, and turns the roadside grass grey.

One such day in July the young owner of Ystrad Farm, that used to lie under Snowdon, went on horseback to the market town at a good rate with a fine cloud of dust chasing him along the road. But the day was over-hot; difficulties arose, tempers inclined to be hasty, the market smelt of hot beasts’ pelts. So young Tom prudently hurried his business and withdrew to the inn to take a leisurely meal and rest till the cool of the evening should tempt him home again.

The sun had been abed an hour when Tom drew near Ystrad. With loose rein he let the mare walk, the deep dust hushing the lazy clop-clop of her hoofs. And Tom fell to dreaming, as one easily may do out in the summer dusk with no one astir but moths and bats and with the sunset colours paling fast but loath to leave the sky.

Presently his way took him along a river-bank, and here was grass to ride on. All at once, a little distance before him and close to the water, Tom noticed a company of people dancing with great mirth and jollity. Their garments were all shining; some were scarlet and gold and orange, like little hot, leaping flames; some blue and pale, like the steady flames from burning wood; and some soft and grey, like curling smoke. They moved in a ring, making intricate patterns but never seeming to break the circle. The mare stopped of her own accord, and Tom sat in the saddle, rigid and watching, as if bewitched. Then suddenly he caught sight of one maiden more lovely than the rest, and after that he had eyes for no one else. In and out she moved among the others, graceful and gay. Tom did a daring deed; he slid noiselessly from the mare’s back, crept along the grass, and seized the maiden.

At the scream she uttered the whole company vanished like one’s breath in July, and Tom was left alone with the beautiful creature weeping in his arms, while the mare quietly cropped the grass beside them. He tried to comfort her; he told her he loved her and would carry her home and make her his wife, but she only shook her head and continued to mourn.

Now Tom had so great a love for her that he could not bear to let her go. In spite of her tears he lifted her to the saddle and led the mare back to Ystrad. He hoped presently to persuade her to marry him, but, though he pleaded, she would consent only to becoming his servant.

And what a good servant she made him! Tom, who had had to make do with hired wenches from neighbouring cottages, hardly knew himself. She could bake and brew, cure meat, preserve the fruit, and make sweet wines, spin and mend, furbish and polish. Everything went so well at Ystrad that folk guessed Tom’s maiden was a fairy. The very herds and fields seemed pleased to do their best for her. As for butter, it was so plentiful that no one thought of weighing it.

From time to time Tom would renew his pleading, only to be met by the same refusal. Now one spring day, when the blossom was on the apple-trees, he chanced to find his fairy maiden out in the orchard. She had taken off her shoes and stockings and was dancing bare-foot on the grass to the music of the birds. He had never seen her so gay since the day he had stolen her from the fairy ring; he began to hope she might relent, and once more he asked her to be his wife. For answer she picked up her shoes and made off through the trees, calling over her shoulder: “Find out my name, and then we will talk of weddings.”

“Find out my name.” It sounded a simple enough condition, but what could Tom do? No one knew the names of the fairies. They do not talk our earth-languages, and few people have learnt theirs. Tom knew of none he could ask for help. His winning the fairy maiden for wife seemed as far off as ever.

Exactly a year had passed since the maid had been found, and once more Tom was riding home to Ystrad through the summer dusk. As before, he let the mare take her own pace, for his thoughts were full of what had happened a year ago. Suddenly, once again he saw the fair company of folk dancing, not more than a few strides away from him. He checked the mare and waited motionless. Presently they stood still, and one of them stepped into the middle of their ring and said in sad tones:

“Ah me! a year ago to-day

Our sister dear was taken away.

Penelope! Penelope!”

At this Tom rose in his stirrups, shouting: “Penelope, Penelope! That’s her name!” and in an instant the whole company had disappeared like one’s breath in July.

What the mare must have thought of Tom’s pace home that night would be hard to say. He made her go like the wind, and as soon as he reached Ystrad he flung himself out of the saddle and rushed into the house. He found the fairy maiden in the big, cool kitchen. It was already dark indoors, and she had lit a lamp, which made a pool of brightness in the dim room. She sat in the light, her fingers busy with sewing, and as she sewed she crooned to herself a certain tune which Tom could never learn, however often he heard it.

“Penelope, Penelope,” Tom called to her joyfully, “I know your name now, Penelope. And so will you wed me?”

When Penelope heard him she wept a little and laughed a little, and, looking into Tom’s face with her strange, clear, green eyes, she said slowly: “I will wed you if you promise never to strike me with iron. If you do that you will sadly rue it.”

Tom found this an easy enough promise to make; the maiden was so precious to him that he could not even imagine himself hurting her.

So the two were wedded.

Ystrad was a very happy place after that. All went well with the farm. Tom was a joyful man and Penelope a good and happy wife, and they loved each other as people should. After a year a little son was born to them, and some time later a little daughter.

It was summer-time again. One of the great Welsh fairs was being held in the neighbourhood. There was a fine to-do at Ystrad one morning, for Tom was going to drive Penelope to the town to see the shows. He went into the meadow near the house to catch a young horse that he meant to use. Penelope stood at the farm door, ready, watching him, for she loved to see his quick, lithe movements. Both of them were feeling happy and excited and a little impatient to be off.

But the young horse was in no mood to be caught. He too felt inclined for holiday-making. Whenever Tom got near he frisked off somewhere else in a tantalizing way. At last Penelope came into the meadow to help Tom, but just as she drew near Tom tried to throw the bridle over the horse’s neck. Penelope ran between them, and the bit struck her shoulder. There was time only for one glance to Tom from her strange green eyes and she was gone. She had vanished like one’s breath in July.

“She had vanished like one’s breath in July.” The Fairy Maiden by Honor Appleton from Legendary Stories of Wales

For days Tom could not believe that she had really disappeared. He kept thinking of her, expecting to hear her step, longing to see her face. He would stay for hours in the meadow, waiting and hoping, but there was no sign, and poor Tom had to turn sorrowfully to the care of the home and the farm with no one to help him. He still had the children, it is true, but they at times only made his grief the harder by asking him for their mother.

The long days of summer slipped away; now it was autumn, and now winter, and still no sign from Penelope. And only once did she come back. One bitterly cold night Tom was sitting in the ingle; the children had gone to bed; the farm-servants had finished work; he was quite alone in the big kitchen with the fire for company. Presently he thought he heard the sound of the queer little tune Penelope used to croon. Could it be the wind in the trees round the house? He pushed open a casement window, leaned out, and listened. There was scarcely a breath of wind; it was a night of still, black frost, starless and silent. And the tune, unmistakably, was the one he knew so well; it was Penelope singing, and the words came clearly to his ear:

“Chill is the night—my son may feel the cold ;

Do thou his father’s coat around him fold.

Lest any harm should to my baby hap,

Do thou her mother’s mantle round her wrap.”

That was all. Tom called her name softly into the darkness, but there was no answer. He shut the window and went gently upstairs to see that the children were warm and safe, and as he looked at them some of the bitterness of his grief for Penelope left him, and instead came peace and comfort.

Legendary Stories Of Wales – Illustrated by Honor Appleton

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save

Save