The Doom of Loki and His Children

The story of three foul offspring, a magic thread made from the breath of a fish, and a venomous punishment.

The Doom of Loki and His Children

A Norse Tale

IT seemed a strange thing that for so many years Odin should have permitted Loki to roam about at pleasure, practising his harmful devices against both gods and men. Yet in truth Allfather, despite his wisdom, was not allowed by the Fates to know or see everything, and often his hand was held against his will by a power above him, whose omnipotence he felt, yet could not explain.

Whether Loki was blood-brother to the King, born in those far-off times before the giant Ymir’s brood had been drowned, whether he was a son of Bergelmer, the only monster who escaped the flood; or whether he was true son of Odin, bred in virtue, but led astray by the Jotuns, no one knew. Yet certain it is, that he would long before have been cast out of the sacred city, had there not existed betwixt him and Allfather a mysterious bond, and had he not so often used his cunning brains to extricate the gods from difficulties into which, as often as not, he had himself led them.

When, however, his love of evil could no longer be ignored—yet before his greatest and final crime, the betrayal of Baldur—Odin decided to call a council of all his sons, and seek their advice on this difficult matter.

“Who is there among ye,” he said, “that can tell me why Loki is lately grown from mere mischief-maker into downright evildoer? And where does he spend those long absences from his palace, which grieve the heart of his gentle wife Sigyn?” Then Heimdall, whose watchful eye never slumbered, came forward.

“Father, he goes to a wood in Jotunheim, called Jarnvid, and there dwells with the hideous giantess Angurbod, whom, indeed, he has married, notwithstanding his vows to Sigyn. He is at this moment playing with his three monstrous children, while Angurbod watches and encourages them. It is from these creatures that he learns his wickedness.”

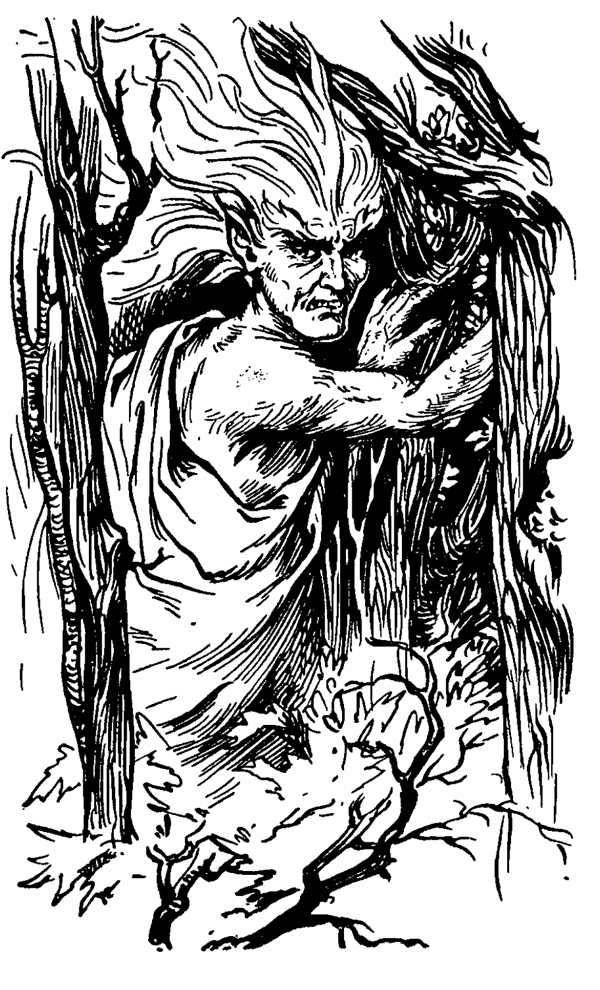

The gods groaned with horror as the full perfidy of Loki was made known to them; and Odin at once ascended his air-throne and cast his gaze towards the wood Jarnvid. There, just as Heimdall had said, he saw Loki sporting in the porch of Angurbod’s house with three frightful forms, evidently his children. One was like a large and loathsome serpent, yet with a face that bespoke more than serpent craft. One was a fierce-fanged wolf. And the last was no other than Hel, whose face and figure could never be described, so terrible were they.

Allfather dispatched his two strongest sons, Thor and Tyr, to fetch up the culprit and his misshapen family, for judgment. At first Loki refused to obey, but soon the threats of Thor frightened his craven heart into submission, and the procession started. The serpent writhed along in front, the wolf leapt from side to side, and Loki led Hel by the hand, while Tyr and Thor marched behind brandishing sword and club. In this order they reached Asgard and followed by all the amazed and horror-stricken gods, made their way to the Great Judgment Hall, where Odin sat waiting.

For a few moments Allfather gazed down upon the monsters, unable to speak; then in stern tones he addressed the Fire-god, who stood stubborn and defiant before him.

“These, then, O Deceiver, are thy foul offspring, and Angurbod it is who has helped thee on thy downward course? No longer may such plagues as these three creatures thrive at large; hear their doom. The serpent shall be cast into the depths of the sea which separates Midgard from Jotunheim; he shall be called Jormungand, the Sea-Snake, and there must he stay buried until the Fates release him. The wolf shall be called Fenris, and he shall be penned in a courtyard on the outskirts of Asgard, fed and looked to by Tyr, who alone is strong enough to control him. Thy daughter Hel, whose hand thou holdest so fondly, shall depart to her appointed place. A throne awaits her in the Underworld, and she shall rule over the kingdom of Death. As for thee, Loki, stripped of these evil children, perchance thy love of evil will lessen, and for the sake of the bond between us, thou shalt keep thy freedom a little longer.”

Thus was judgment passed upon the children of Loki and Angurbod; Odin’s behests were carried out, and for a time all went well. But Fenris grew mightier and fiercer each day, and his cries of hunger before Tyr went to feed him, and his howls of greed as he tore his meat, oppressed all the dwellers in the city, until at length they appealed to their King, saying—

“Allfather, we fear that soon Fenris will grow beyond the control of Tyr, and breaking from his pen will devour us all. Give us, therefore, a chain with which to bind him.”

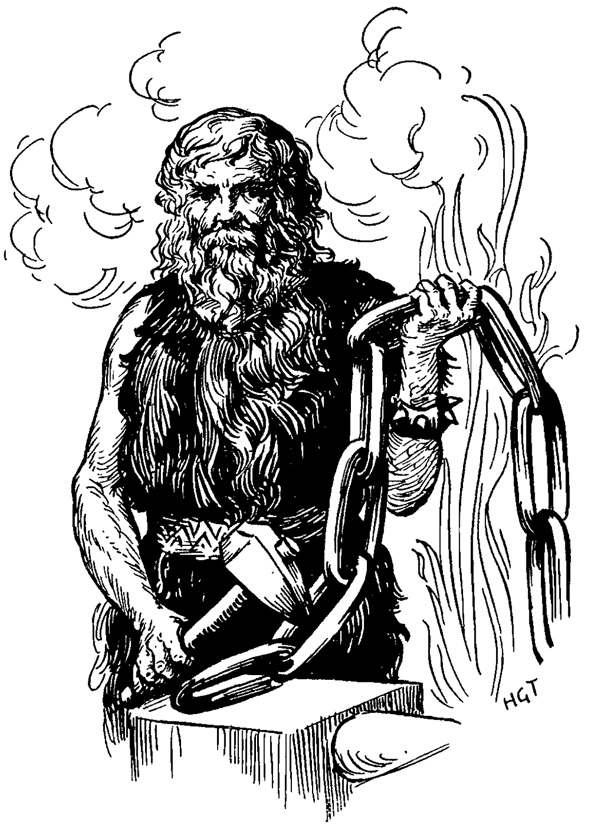

Odin answered that he had no such chain to bestow, but if they wished, they might make or seek one. At this, Thor readily offered to put Miolnir to such good use on his anvil, that an unbreakable chain should be finished by the next morning. And all that night the sounds of hammering proceeded from his smithy, and the sparks flew for miles around, and the bellows blew a hurricane. At dawn Thor emerged black with toil, holding out to the assembled gods the chain Laeding, more mighty in each of its links and more virtuous in its metal than any one could have dreamed. Nevertheless, when they had bound Fenris, neck and foot with it, he merely shook himself, and the links tore like paper.

Thor ground his teeth, but went back to his smithy and worked again, this time for a day and a night, until he had forged Dromi, which was as strong again as Læding; and for the second time they bound Fenris, neck and foot. But the wolf only stretched himself, and Dromi fell into as many pieces as Læding.

The gods went away crestfallen, Thor muttering aloud, “Look not to me for further help. Who is there in the world that can forge more strongly than I?” To which, indeed, there seemed no reply.

Some time passed, and the power and fury of Fenris doubled itself, until Tyr told his brethren that before many more days the beast would certainly break from his pen and wreak mischief in the city. Then Hermod raised his voice.

“Why not send to the King of the Dwarfs who lives in Swartheim?” he asked. “Have not the little cave-men fashioned Draupnir, Allfather’s wondrous ring? And the ship Skidbladnir, that defies all weather? And Thor’s hammer, and endless other marvels? Perchance with their spells they can weave a chain to bind Fenris.”

Whereupon the messenger of the Vans, Skyrnir, who knew the land of Swartheim, was dispatched with presents and promises to the Dwarf King, and he, when he had heard the gods’ request, thought for a while with pursed lips and wrinkled brow.

“Yes,” he said at length, “it may be done. Wait here for three days and at the end of that time the chain shall be ready.”

So Skyrnir waited, and on the third day the King put into his hand a soft silken thread, so fine that it could pass through the eye of a needle, and so light in weight that it floated in the air like a piece of fluff.

“You think this will never hold Fenris?” asked the King with a laugh, as he read doubt and surprise on Skyrnir’s face. “I will tell you what it is made of. It is fashioned out of six things—a cat’s footfall, a woman’s beard, the roots of a mountain, the sinews of a bear, the breath of a fish, and the spittle of a bird. No strength, however great, can break such a chain—nothing but the sound of the trumpets calling to the Last Battle.”

Skyrnir now hurried back to Asgard with his treasure, and greatly did the gods marvel as they tried, one by one, and all unsuccessfully, to break or cut the thread. A pleased smile lit up Odin’s face as he, with the rest, examined it.

“Go now, my sons,” he said, “and if ye succeed in beguiling the wolf to wear this fetter, methinks ye will have no further trouble with him.”

But when Fenris saw the delicate thread which the gods had brought, he feared magic, against which he knew his strength was useless. At length he said that he would stand and allow them to wind it about him, if one of them would place a hand within his mouth as a sign of good faith. There was a moment’s silence, and then Tyr strode forward and calmly placed the whole of his right arm within the cruel, hungry jaws. Quickly Thor and the rest wound the thread about the wolf’s head, and round his legs, and fastened it firmly to the largest flagstone in the court. Fenris plunged forward, expecting his bond to give like burnt cotton, but the more he struggled, the firmer did he find himself fettered. With an angry snarl he bit off Tyr’s hand. He had been beguiled, but he had claimed his hostage.

Loki’s three evil children were now safely put into bondage, and there they would remain until the Last Day, when both gods and giants should perish. But their father went free, and instead of diminishing in evil, as Odin had hoped, he became less and less like a god, more and more like a devil, until at length, as you know, he committed the greatest treason of all, by betraying Baldur into the power of his daughter Hel.

After that, Allfather could no longer remember the mystic bond which bound him to the Fire-god, and he gave orders that if ever the Deceiver appeared again in Asgard he should be seized and held prisoner. Loki knew full well that his crime against Baldur had won him universal hate, so to escape punishment he fled from the Peacestead on that fatal day, and hid in the mountains; and there he built himself a dwelling with four doors, looking north, south, east, and west, and the doors he kept always open. By this means he hoped to be sure of escape if ever the avenging gods should seek and discover him. He planned carefully, that as soon as he should see his foes approaching, he would rush out towards the mountain stream which ran down not far from his hut. There he would turn himself into a salmon, and hide among the stones and weeds.

“Nevertheless,” he said to himself, “though I could easily escape a rod and hook, they could catch me if they made a net like that of the Sea-Goddess Ran.”

And this fear so haunted him that he decided to prove whether such a net could be made. One day he was busily at work with his twine and flax when a sudden dart of flame from the hearth made him look up. In the distance he saw Odin, Thor, and many other gods hurrying towards the hut. He sprang up, threw the net into the fire and dashed out towards the stream unperceived, so that when the gods entered they found their enemy gone, and nothing but a half-burned net smouldering on the hearth, and some unused twine on the floor.

“What,” said one of them, “if he has been testing the power of nets to catch fish? Let us see if the stream yonder be worth dragging.”

And they began, with the rest of Loki’s twine, to make a net similar to the pieces they saw smouldering. When it was finished they carried it out and cast it into the water, and dragged the stream thoroughly. But Loki, in the form of a salmon, hid between two stones and escaped. A second time they dragged, and now the net was weighted so that it brought to the surface even stones. A large salmon came up, leapt high in the air, and dropped into the water.

“’Tis he,” shouted Thor. “Once more, brothers, and our enemy will be captured.”

Again the net was cast, and this time, as the salmon leapt, Thor caught it by the tail and held it fast, until, almost dead with struggling, it lay faint and still.

“Put on your true form,” cried the captor, and the salmon changed to Loki, who sullenly allowed himself to be bound, for he knew that no further fighting could avail him.

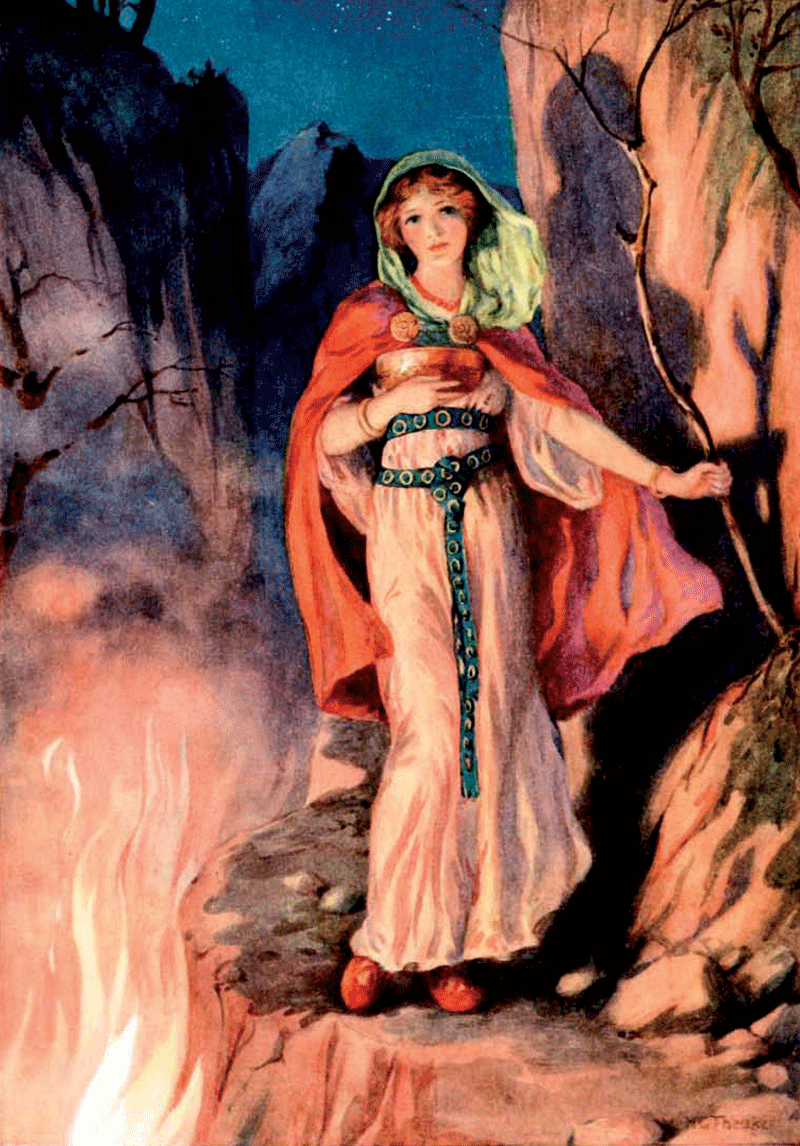

The gods then led him down to a cavern in the very bowels of the earth, and there fettered him to three pointed rocks, one for his shoulders, one for his waist, and one for his knees. Over his head the Giantess Skadi, his ancient foe, hung a venomous serpent, from whose mouth fell drops of poison, which burnt and stung like scalding water. Such torment, however, was too terrible, even for treacherous Loki, and Sigyn, his gentle wife, was allowed to descend to the cavern with a bowl, which she held aloft for ever after, catching in it the drops of venom as they fell. Only when she moved to empty the vessel did the drops hiss upon the Deceiver’s upturned face, and then he shook the whole earth in his struggles to get free.

Such was the fate of Loki, doomed to lie unpitied, unrelieved, until the Great Day of Doom, Ragnarok, should come. Then he, with his children, and all other evil things, should be loosed from bondage, and the whole Universe should collapse by reason of the mighty struggle between them and the gods. Both sides should perish in the conflict, and out of the destruction should arise a new Asgard and Midgard, new forms of the gods, new men and women, fairer and more virtuous than of old. But Loki and the giants, with all their sin and kin, should have vanished for ever.