Beauty and the Beast – and other tales of love in unexpected places.

This book is part of our beloved Origins of Fairy Tales from Around the World Series which showcases the amazing breath and diversity involved in folkloric storytelling. It focuses on the phenomenon that the same tales, with only minor variations, appear again and again in different cultures – across time and geographical space. The tales included in these collections are enhanced by the addition of stunning illustrations by talented artists from the Golden Age of Illustration.Beauty and the Beast – and other tales of love in unexpected places

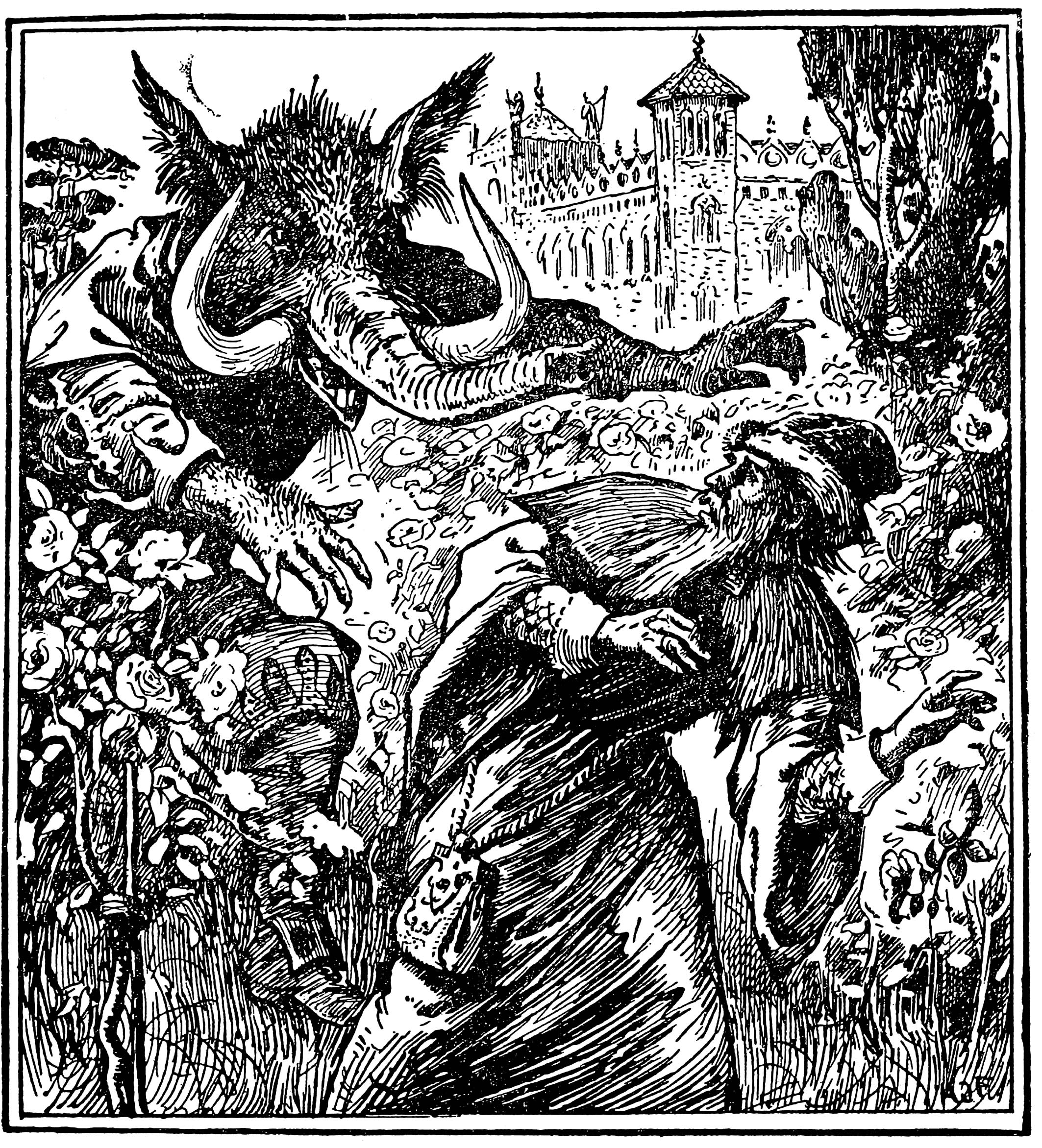

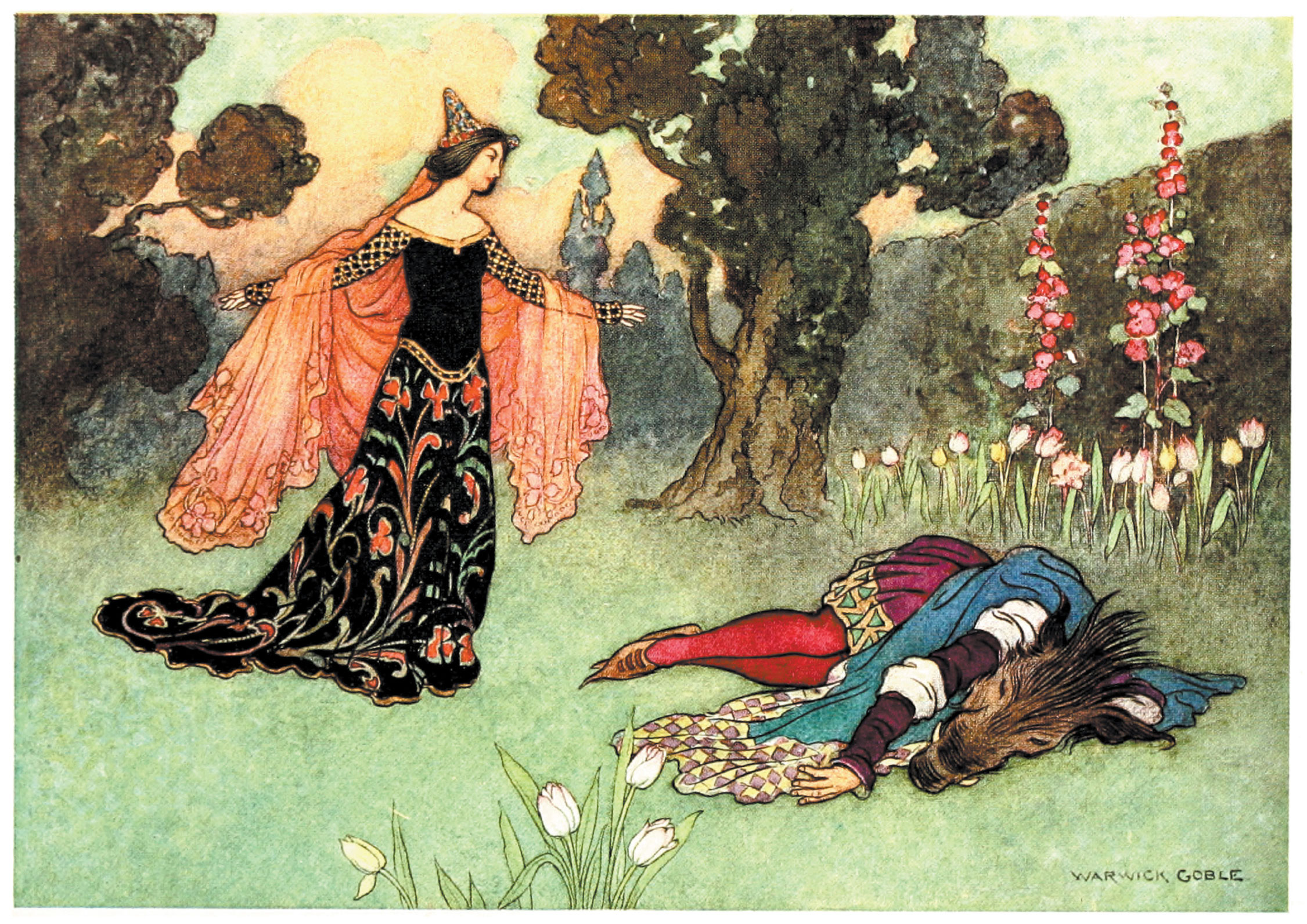

“At last she remembered her dream, rushed to the grass-plot, and there saw him lying apparently dead.” Illustration by Warwick Goble.

” Beauty and the Beast has a fascinating history, first starting with Madame Gabrielle-Suzanne de Villeneuve (1695 – 1755). Villeneuve’s La Belle et La Bête was an original piece of storytelling, first published in La Jeune Américaine, et Les Contes Marins in 1740. However, the tale has gone through many varied and imaginative incarnations, but remaining constant are the themes of envy unrewarded, of learning to love what may at first appear a ‘beast’ and the benefits which virtue and selflessness will bestow on the individual.”

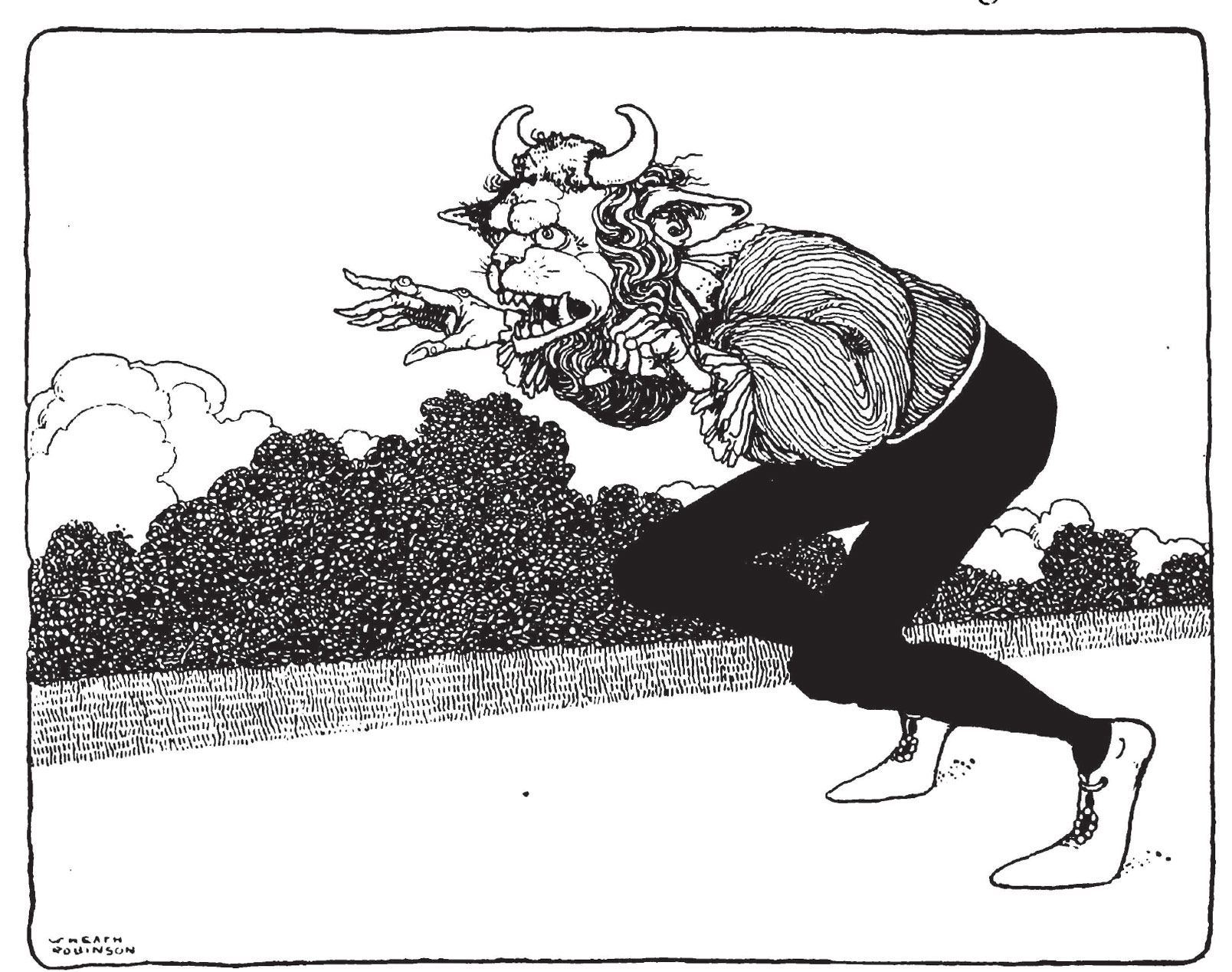

‘Beauty and the Beast’ Illustration by Anne Anderson

The stories within:

Cupid and Psyche (A Roman / African Tale)

A story first told by Lucius Apuleius Madaurensis (c. 125 – 180 CE). Its similarities with later versions of ‘Beauty and the Beast’ are striking; particularly Psyche’s curiosity, her subsequent banishment, the role of her deceptive sisters, and true love eventually ensuring the pair’s eternal union.

La Belle et La Bête (A French Tale)

This story was first published by Jeanne-Marie Leprince de Beaumont in 1756, as ‘a tale for the entertainment of juvenile readers.’ Although similar in the overall plot, Beaumont changed many aspects of Villeneuve’s original, omitting various details to fit a younger audience and giving a more didactic message about good manners and behaviour.

Zelinda and the Monster (An Italian Tale)

‘Zelinda and the Monster’ was recorded in Thomas Frederick Crane’s Italian Popular Tales, published in 1885. This tale differs from the classic Beaumont version, in that the father is depicted as a poor man, with only three daughters instead of six children. The ‘Beast’ is no ordinary beast in this version either, but a fire-breathing dragon who requests the presence of his daughter.

The Maiden and the Beast (A Portuguese Tale)

This tale comes from an anthology of Portuguese Folk-Tales, compiled by Zófimo Consiglieri Pedroso (1851 – 1910). ‘The Maiden and the Beast’ differs from most other ‘beauty and the beast’ tales in that the youngest daughter does not ask for a rose, but merely wishes for her ‘dear father’s health.’ Pressured, she then asks for ‘a slice of roach from a green meadow’ – a request which spells disastrous consequences.

Beauty and the Beast (An English Tale)

‘Beauty and the Beast’ was written down by the Scottish folklorist Andrew Lang (1844 – 1912), in The Blue Fairy Book (1889). Lang’s tale is a complex mixture of Beaumont and Villeneuve’s stories, but encompasses more of the fine details, and character development of Villeneuve. Lang was determined to collate as much original folkloric storytelling as possible.

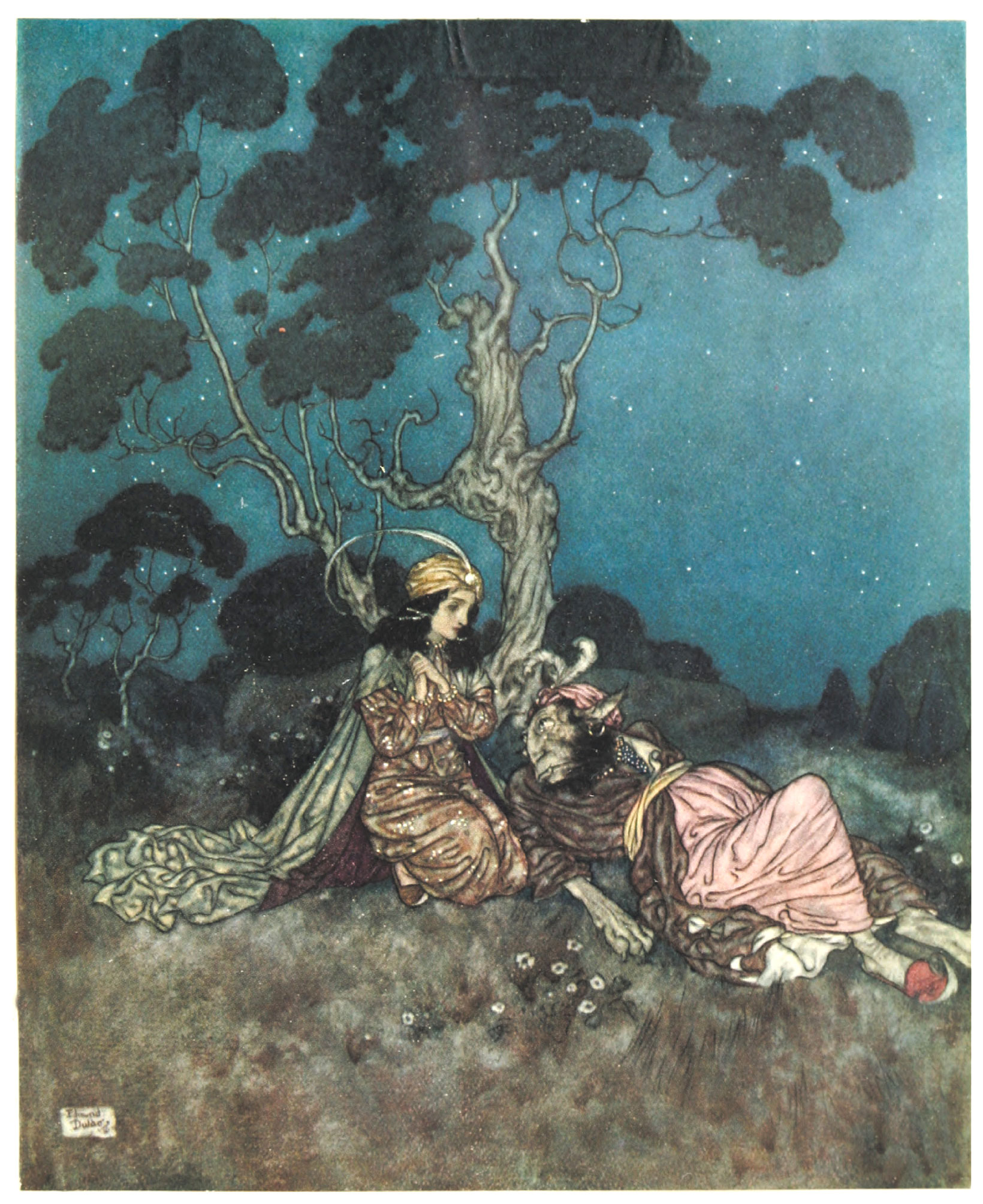

‘Ah! What a fright you have given me! She murmured.’ Illustration by Edmund Dulac

The Fairy Serpent (A Chinese Tale)

‘The Fairy Serpent’ was published in Adele M. Fielde’s Chinese Nights Entertainments a text which appeared in 1893. Her version of the Chinese tale of ‘The Fairy Serpent’ most likely derives from the ancient Indian text, the Panchatantra. The original Sanskrit work, contained the narrative of ‘The woman who married a snake’ – of which obvious parallels are seen in this narrative. In all early societies, young girls were given in marriage by their fathers, and would have very often had to ‘learn to love’ men who first appeared as ‘monsters.’

The Enchanted Tsarévich (A Russian Tale)

‘The Enchanted Tsarévich’ was written down by Leonard Arthur Magnus (1879 – 1924) in Russian Folk Tales, 1916. In this version, similarly to the story of ‘Zelinda and the Monster’, the father is a merchant with three daughters. This time though, the monster is a winged snake, as usual requesting the father’s youngest daughter after catching him picking a beautiful rose. When the young girl is living in the castle, each night the snake asks her to draw his bed a little closer; outside her door, in her room – and finally in her bed.

We hope you’ve enjoyed reading about this classic fairy tale and it’s many variations from around the world.

If you would like to purchase this book to read these tales in full click here.

If you would like to read more about Beauty and the Beast visit our page on the History of Beauty and the Beast.