John Ruskin Biography

John Ruskin was born on 8th February 1819, in London, England. He was the leading art critic of the Victorian era, as well as an art patron, draughtsman, watercolourist, a prominent social thinker and philanthropist.

During his lifetime, John Ruskin wrote on an amazing array of subjects; ranging from geology to architecture, myth to ornithology, literature to education, and botany to political economy. His writing styles and literary forms were equally varied. Ruskin penned essays and treatises, poetry and lectures, travel guides and manuals, letters and even a fairy tale. In all of his writing though, he emphasised the connections between nature, art and society.

John Ruskin was born at 54 Hunter Street, Brunswick Square (just south of St Pancras railway station). His childhood was characterised by the contrasting influences of his father and mother, both fiercely ambitious for him. John James Ruskin helped to develop his son’s Romanticism, whilst his mother, Margaret (an Evangelical Christian), taught her son to read the King James Bible from beginning to end. Ruskin was later enrolled into King’s College in London, before being admitted to Christ Church College, Oxford University (which he attended from 1836 – 1842), where he won the Newdigate prize for his poetry.

SELECTED BOOKS

From late 1840 to autumn 1842, John Ruskin spent most of his time abroad with his parents, principally in Italy. His first major text was published on his return to England – Modern Painters in 1843. Ruskin was galvanised into writing a defence of J. M. W. Turner when he read an attack on several of Turner’s pictures exhibited at the Royal Academy. The work promoted many modern landscape painters, specifically Turner, who was in Ruskin’s opinion, a far greater talent than most other artists of the era – able to express the ‘truths’ of nature. These remarks brought Ruskin substantial criticism at the time, as many art critics saw Turner’s work as meaningless and messy, taking Ruskin’s comments as an affront to the other great artists of the period. Some commentators were impressed by the young man’s work however, notably Charlotte Bronte and Elizabeth Gaskell.

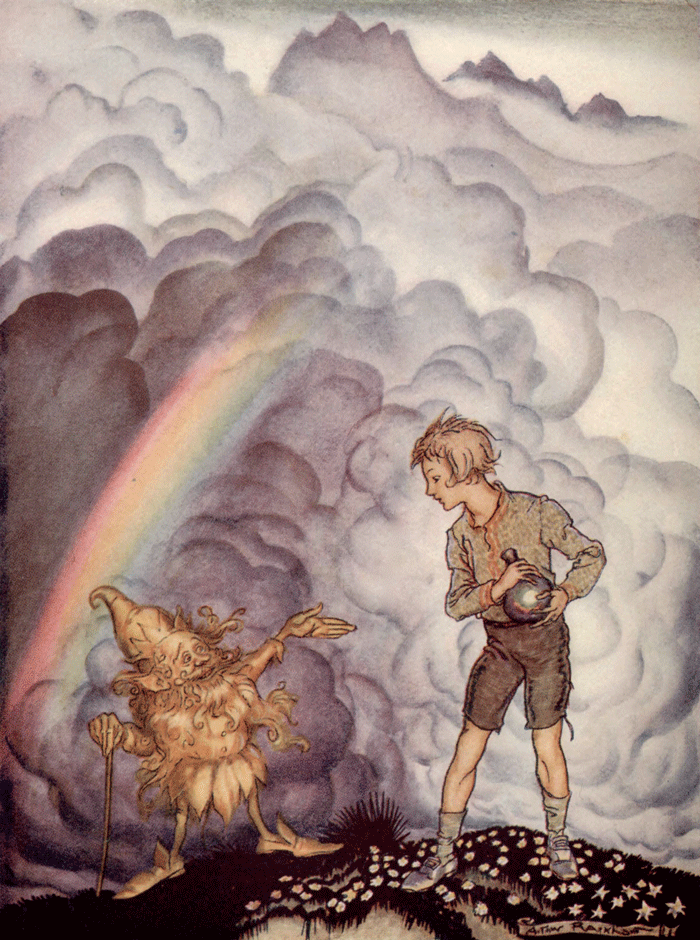

In 1848, John Ruskin married Effie Grey. It was around this time that he wrote his early novel, The King of the Golden River, dedicating it to her. Their early life was spent at 31 Park Street, Mayfair, a house secured for them by Ruskin’s father. Effie was too ill to undertake their European tour of 1849, so Ruskin visited the Alps with his parents, gathering material for the third and fourth volumes of Modern Painters. He was struck by the contrast between the Alpine beauty and the poverty of the area’s people – stirring his social conscience that became increasingly sensitive.

John Ruskin’s marriage was unsuccessful however, and they separated in 1854. Grey went on to marry the artist John Everett Millais. Millais and Ruskin had been friends since the late 1840s, when one of Millais paintings (Christ in the House of his Parents) caused controversy for alleged immorality. Ruskin defended Millais, until the intimacy between Effie and Millais was disclosed.

John Ruskin then turned his attentions to architecture, and particularly Gothic revival styles, which led to another great work, The Seven Lamps of Architecture (published in 1849). Ruskin also penned The Stones of Venice (1851-53), which he had done the studies for during a trip with Effie. Developing from a technical history of Venetian architecture, from the Romanesque to the Renaissance, into a broad cultural history, Stones also reflected Ruskin’s view of contemporary England. It acted as a warning about the moral and spiritual health of society, using the deterioration of Venice as an example.

From the 1850s onwards, John Ruskin championed the Pre-Raphaelites who were in turn, greatly influenced by his ideas. By 1858, Ruskin was again travelling in Europe. The tour took him from Switzerland to Turin where he saw Paolo Veronese’s Presentation of the Queen of Sheba. He would later claim (in April 1877) that the discovery of this painting, contrasting starkly with a particularly dull sermon, led to his ‘unconversion’ from Evangelical Christianity. But in reality he had doubted his Evangelical Christian faith for some time, threatened by Biblical and geological scholarship that had undermined the literal truth and absolute authority of the Bible.

John Ruskin fell in love a second time, again in 1858 (an eventful year) – with Rose La Touché. The couple courted for a long time, with Ruskin making several marriage proposals. She rejected him in 1872 however, and died soon after. This was a devastating blow to Ruskin, who soon slipped into a state of mental illness and despair, suffering several breakdowns.

In later life, John Ruskin became heavily involved in the world of education, and in 1885, founded a School of Art in Sidney Street, Cambridge, which later became known as Anglia Ruskin University. In 1869, Ruskin also became the first Slade Professor of Fine Art at the University of Oxford, where he established the Ruskin School of Drawing. Ever the fervent critic, it was during this time that Ruskin also moved into political commentary. In 1871, he began his monthly ‘letters to the workmen and labourers of Great Britain’, published under the title Fors Clavigera (1871–1884). In the course of this complex and deeply personal work, he developed the principles underlying his ideal society. As a result, he founded the ‘Guild of St George’ (a charitable education trust); an organisation that endures today.

John Ruskin’s outlook in socialism played a key role in the growth of Christian socialism in Britain. He wrote Unto This Last (1860), which he described as the central work of his life – a text on the economy and employment systems more specifically. Ruskin’s political ideas, and Unto This Last in particular, were praised and paraphrased by Mohandas Gandhi, a wide range of autodidacts, the economist John A. Hobson and many of the founders of the British Labour party.

In his later life, John Ruskin continued writing reviews and articles that often caused controversy and even law suits. In one of such cases, he was sued by James McNeill Whistler in 1878. Though he was ordered to pay only a small amount as compensation, Ruskin’s reputation was badly affected after the incident. In the 1880s, he returned to simpler themes that had been among his favourites since childhood. He wrote about Walter Scott, Byron and Wordsworth in Fiction, Fair and Foul (1880) and returned to meteorological observations in his lectures, The Storm-Cloud of the Nineteenth-Century (1884), describing the apparent effects of industrialisation on weather patterns. John Ruskin’s Storm-Cloud has been seen as foreshadowing environmentalism and related concerns in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries.

The period from the late 1880s onwards was one of steady and inexorable decline. Gradually it became too difficult for Ruskin to travel to Europe. He suffered a complete collapse on his final tour, which included Beauvais, Sallanches and Venice, in 1888. The emergence and dominance of the Aesthetic movement and Impressionism distanced Ruskin from the modern art world, his ideas on the social utility of art contrasting with the ‘art for art’s sake’ that was beginning to dominate. His later writings were increasingly seen as irrelevant, especially as he seemed to be more interested in book illustrators such as Kate Greenaway than in modern art. He also attacked Darwinian theory with increasing violence, although he knew and respected Darwin personally.

John Ruskin died his home at Brantwood, Cumbria (from influenza), on 20th January 1900, at the age of eighty. Today, his works are widely read and respected, appearing in many translations, all over the globe.