The Little Picture Girl – A Christmas Story

Christmas eve magic, a picture that comes to life, and a visit from Father Christmas.

The Little Picture Girl

– A Christmas Story –

IT was Christmas Eve, and a little girl lay in her little bed, wondering what Santa Claus was going to put in her stocking this year. It was hung up where he would be sure to see it, and upon the same chair before the fireplace she had thoughtfully placed her clothes-brush in case he might like to brush off the soot from his coat.

The grate held but a few smouldering embers, for it was late, very late—at least ten o’clock—and Minna ought to have been asleep hours ago. Perhaps she would have been, only there were so many things to wonder about to-night, and one cannot be sure of wondering about them when one is fast asleep.

So after wondering about Santa Claus, she turned to the stars, which she could see through the uncurtained window: she wondered if they twinkled and winked like that because they liked it or because she liked it. Then there was the moon, which was looking straight at her in its own unblushing, beaming way and filled the room with its light; and she sat up in bed and watched it, wondering where it went to during the day.

Now opposite her bed were three pictures, coloured and framed. One was of a dainty Columbine smiling at her companion picture—a Harlequin who stood on his toes with feet crossed, and his arms folded over his staff; and the pair set her wondering what she would see at the promised pantomime.

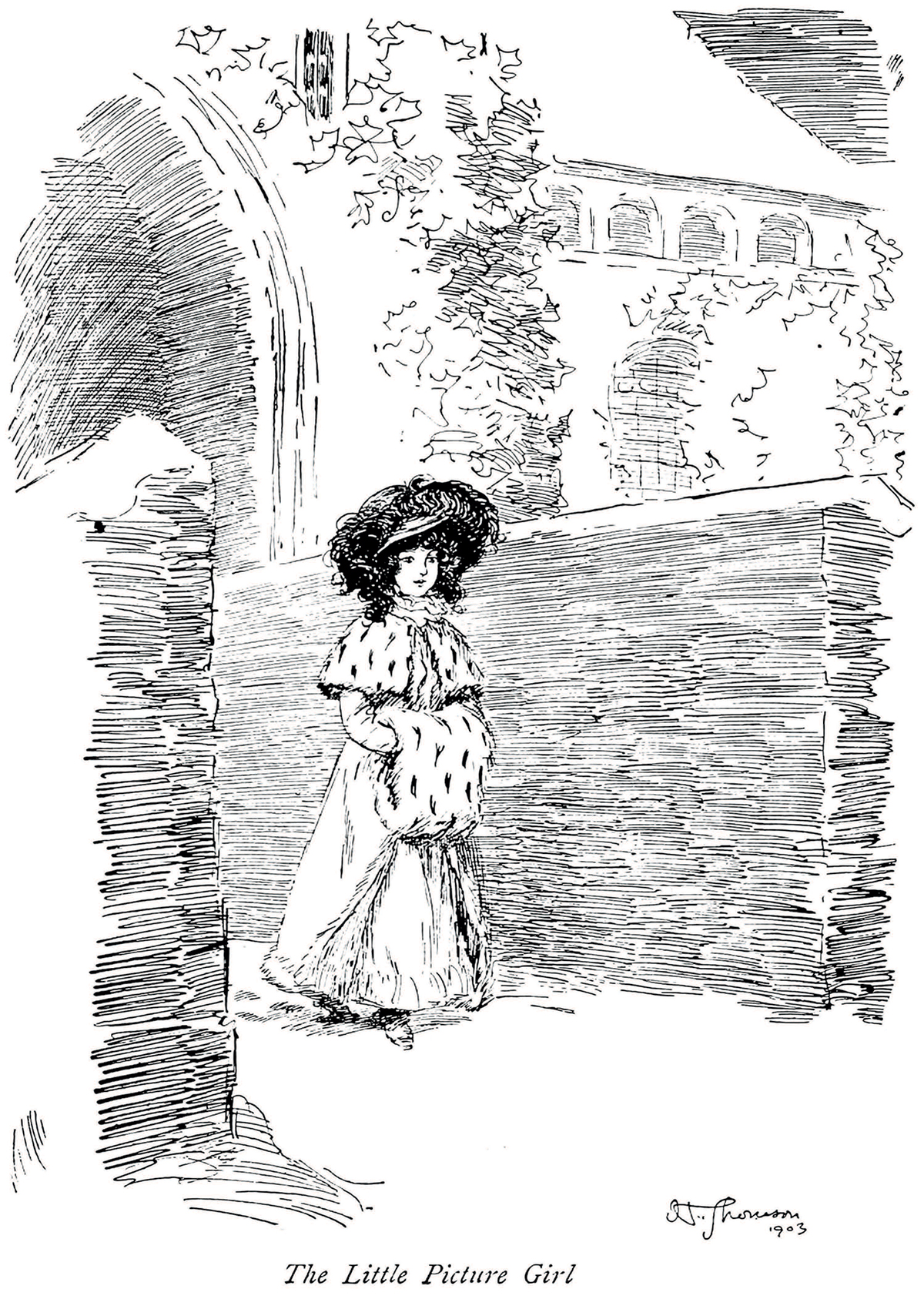

Between them hung Minna’s favourite picture. It represented a fine old moated house covered with snow. On the white path which led from the portico were tracks of little feet, manifestly made by the little smiling girl who stood in the act of passing over the bridge that spanned the moat. She appeared to be the same age as Minna, about six years old, and was dressed in a red pelisse and fur tippet. Her dark hair peeped from under a red, broad-brimmed hat with drooping feathers, and her hands were hidden in a large fur muff.

Minna herself had just such an outdoor costume, and when dressed for her walk she had often wondered where the little Picture Girl could be going so gaily for hers. And now Minna wondered that once more as she glanced at her favourite picture, upon which the moon was shining so brightly to-night, till, bathed in the bright light, it seemed to stand right out from the shadows of the room.

Illustration by Hugh Thomson

There was a creak, as though the old wardrobe wanted to stretch itself after standing still so long—a funny little way furniture has now and again. But Minna didn’t think it was the wardrobe this time—she thought Harlequin had done it. For it seemed to her as though he had suddenly stretched forth his arm and struck out with his staff. No—he was just as usual, only somewhat darker, being in shadow; and as usual just ready to do something, yet never doing it.

But surely with the favourite picture there was something different!—some change! It was always morning there. And now—why, now it was night! The moon was lighting up the old moated house, and the stars were twinkling over its heavy, white-capped roof. Minna looked for the little girl in red—but there was no little girl in red on the bridge at all!

“Of course,” reflected Minna, “she must be in bed behind one of those little dormer windows fast asleep—for it must be very late.”

This seemed strange somehow, yet it was only just as it really ought to be. She herself never went for a morning walk in the middle of the night, nor had she ever heard of any one else doing so.

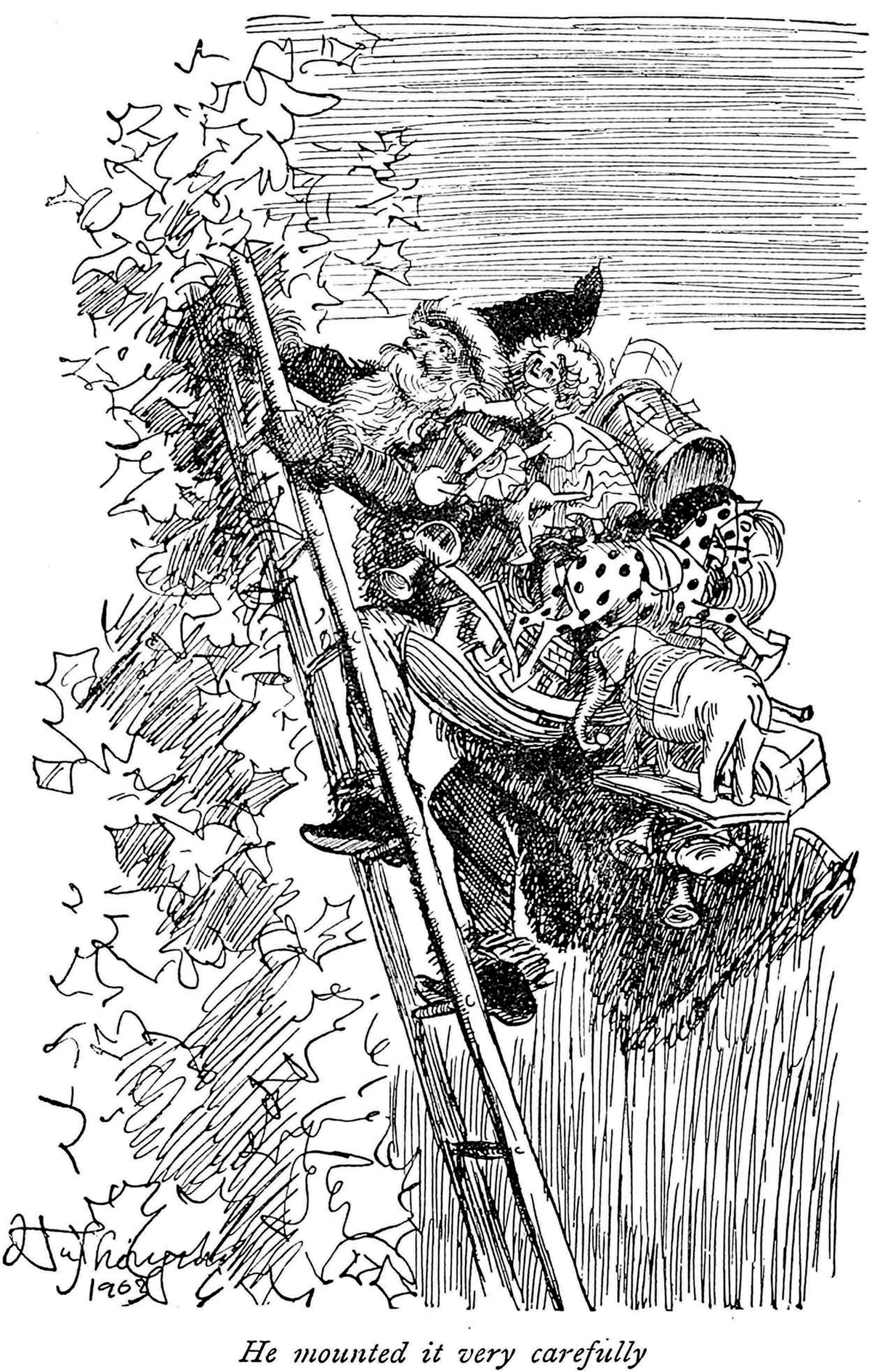

All at once, from the distant steeple which peeped through the white sparkling trees beyond the bridge, came a muffled striking of the hour, and Minna, to her increasing surprise, counted on her fingers up to ten, and then there were two more. And then, to her amazement, whom should she see on the bridge in the snow, which had begun gently to fall again—not the little girl in red—but dear old Santa Claus himself, covered up in fur and scarlet, trudging towards the house with tempting-looking parcels slung about him! Now he fixed a ladder against the thick, frost-laden ivy which covered the front of the old house, and he mounted it very carefully. Then he climbed up the roof as easily as if he had been walking along the highroad in the daylight. And then he disappeared down one of the chimneys. Very soon he reappeared without quite so many parcels, slowly descended the ladder, put it upon his shoulder, and walked off with it.

Minna’s eyes followed him with the utmost astonishment and interest. Of course, she always knew that it was Santa Claus’s lovely privilege to come down the chimney, but she had never actually known him to do it—and then the joy of seeing him come out again, evidently on his rounds, was breathlessly delicious!

Illustration by Hugh Thomson

All was quiet now—only the moon and the stars and Minna watching over the slumbering house and garden, about which the soft snow-flakes hovered and fluttered. She had more than ever to wonder about now. She longed for a peep—just one peep—inside that beautiful house, to see if the little Picture Girl was really asleep.

Harlequin must have guessed what Minna wanted, for there is no doubt that he gave her a knowing look (though it might have been meant for sweet Columbine); and just as surely Minna saw his arm stretch out and heard the rap of his staff upon the picture frame. Then he pretended he hadn’t done it; but she forgot all about him, so great was her interest in what she saw.

At that touch of Harlequin’s the scene had changed to a dainty bedroom. It was dawn. A red pelisse and hat hung upon a peg on the door, and a large muff peeped from its box on the shelf. A rosy light tinged the face of the child who was sleeping there in the old wooden bedstead, and woke her up. The first thing the little Picture Girl did was to look with content into her stocking. It was very fat. And then, with a little pant of delight, she discovered a lovely doll lying on her pillow. First she hugged and then she kissed it; then she laid her new treasure beside her, her heavy eyelids drooped, and she fell asleep again.

And nothing stirred.

“More, please!” said Minna, by this time quite at home with Harlequin. Again he gave that knowing look, and did as she asked. A rap, and once more she saw the garden. It had stopped snowing, and the sun was rising over the old roof.

Suddenly a little sweep appeared, swung himself up by the ivy, crept stealthily up the tiles, and disappeared down a chimney. In a moment he reappeared with a doll and a fat-looking stocking, all so quickly that, before Minna had time to clasp her hands and cry out, he was gone altogether. She looked at Harlequin, but he paid no attention.

“More!” she repeated eagerly. Harlequin’s staff then moved and rapped.

And there was the breakfast-room in the old moated house. The master of it sat at the table reading his newspaper. Soon he looked up and nodded encouragingly at his little daughter, who very seriously was making his tea. She nodded back and smiled. But it was a sad little smile, and her eyes were rather red, as though something had happened.

Then the door opened, and, to every one’s surprise, in marched a stout beadle. In one hand he held a doll and a stocking full of sweets, and in the other he held the collar of a little sweep, with the little sweep wriggling inside it. Close behind there came a tiny crippled girl, who moved painfully by the aid of a crutch to the boy’s side, and laid a trembling hand on his arm. The brother and sister were much like one another, in feature and in squalor. Great tears were rolling down her cheeks, and her poor face was no whiter with pain than his with fright beneath the soot, though, looking lovingly at her, he tried to appear brave.

The beadle noticed the little Picture Girl’s look of recognition at sight of her lost treasures, and as he gave them back to her he pointed to the black marks on the doll’s frock, which tallied with the little sweep’s grimy paw, and then jerked his head towards the crippled child in whose possession he had found them. Then the stout beadle gave the boy a shake, just to remind him of his wrong-doing—as if any further reminder was needed!—and made for the door, dragging the wretched offender after him.

But the little Picture Girl showed so much distress, stopped him, and looked at him so piteously, and with so much kindness in her sweet eyes, that he let go his grip of the collar. Then she put the presents into the boy’s hand, and pushed him gently towards his sister. But the lad shook his head sadly, and looked more ashamed than ever.

The little Picture Girl glanced at her father, who had been silently watching the scene. He nodded, so she pressed them on the boy, whose eyes now filled with tears as he gazed, humbled and grateful, at the beautiful young lady whose generosity saved him from punishment. Meanwhile, the gentleman Christmas-boxed the beadle, who smiled fatly and went his way. Then, for a moment or two, the picture-father’s uplifted finger wagged a warning at the boy, who hung his head: but Minna could see that it was not so very terrible, because, if the boy had not confessed his fault, how would the beadle have known in what house he had yielded to temptation for his sister’s sake? The little cripple dried her eyes at seeing her brother safe, and was very grateful for the gifts she hesitated to accept. But she had a right to keep them now; and it was not her fault that she was the innocent cause of her brother’s offence.

Food from the breakfast-table was wrapped up in the newspaper, the big bundle was put into the little sweep’s arms, and the two poor waifs who had entered so miserable were sent away happy at the bright moment which had entered into their dark lives, whilst the little Picture Girl, who for the second time had lost the presents Santa Claus had brought her, looked after the poor little pair quite content, and smiled as she waved good-bye with her pretty hand.

Then the master of the old moated house wiped his spectacles, which somehow had become quite misty. He lifted up his little daughter in his arms and kissed her, and, putting his hand into his pocket, drew from his purse a gold piece which she took with a laugh of surprise and delight, and threw her arms round his dear bronzed neck.

Minna saw nothing more. She must have fallen fast asleep.

It was very late when she awoke. The first thing she did was to smile as she trotted off to look at what Santa Claus had put in her stocking. She had seen him on his rounds. She had seen his parcels. Dear, kind old Santa Claus, who saves up all the year to be the loving, generous friend to little children at Christmas-time. Minna smiled again as the thought flashed through her mind. She approached her stocking. It looked rather thin—horridly thin. It was empty! She ran to her pillow. Nothing on it, nothing under it! She could not understand it. Oh, Santa Claus!

She gave a big gulp, and decided to wait and see what her father would say about it. She had to bustle too, for the bell would very soon ring for breakfast, at which it was her duty to preside.

“Papa, Santa Claus has forgotten me!” were her first words after the morning kiss.

At this, her father pursed up his lips with a blank look. “Dear, dear! Good gracious! ’Pon my word! What a forgetful old Santa Claus. I’m afraid he’s getting past his work. Perhaps,” he said, turning to the window, as a tear was gathering in each of Minna’s bright eyes, “the snow was too thick.”

Illustration by Hugh Thomson

“No, Funnyums” (she often called him that), “it wasn’t the snow. I know he was out in it, ’cos I saw him.”

“Saw him, did you?” he replied, smiling. “Well, perhaps he gave all the toys away till there were none left, and then, as the shops were shut, there were no more to be had!”

Minna now felt sure her father was joking as usual, and that there must be some secret.

“But perhaps, Minna, Santa Claus came to my room by mistake,” he added. “In fact, it occurred to me that he might. He’s getting short-sighted, you know, and—we are so very much alike. Suppose you go and see!”

Away she ran, and there, sure enough, were Funnyums’s two socks hung up! One looked full, the other looked empty. She found in the full one all sorts of good things to eat. Minna emptied it quickly.

“I wish Funnyums wore stockings,” she murmured. Then she went to the empty one, which wasn’t empty, because right down in the toe there was a gold piece!

Then Funnyums was hugged, and Funnyums was thanked, and scolded for being up to his tricks again, and then hugged once more to make it all right. All that stirring time he was quietly pretending to read his newspaper—just as though he really wanted to read it at all!

And Minna forgot everything in the excitement of Christmas Day. That night she slept soundly. The following day she went to the pantomime, and afterwards dreamt about Columbine.

It was only on the morrow that she noticed again her favourite picture, and then her mind wandered back to the wonderful things that had happened there. And as she gazed at the little girl in red, who was going out so joyously for her morning walk, it occurred to her where the little Picture Girl must be going to—she was going out, as Minna was, to spend the gold piece her father had given her!

“Ah, she deserved it,” Minna said to herself. “I—I don’t quite think I’ve deserved mine—that is, quite so much. I should like to do something for children who suffer and are poor,” she muttered, “like—like the children in the hospital.” And slowly, as she thought it out, she made up her mind that the doll she was going to buy should be a very small one, and that the rest of the money from the gold piece she would send to the “Children’s Hospital Fund.”

Seldom has any child felt happier than Minna did that sunny morning as she donned her red pelisse and hat, and took her muff from its box. She paused at the door, and glanced at the little Picture Girl, who was smiling back at her. “A Merry Christmas and a Happy New Year!” said Minna out loud, dropped her a little curtsey, nodded gaily, and ran out.

This story was taken from the book:

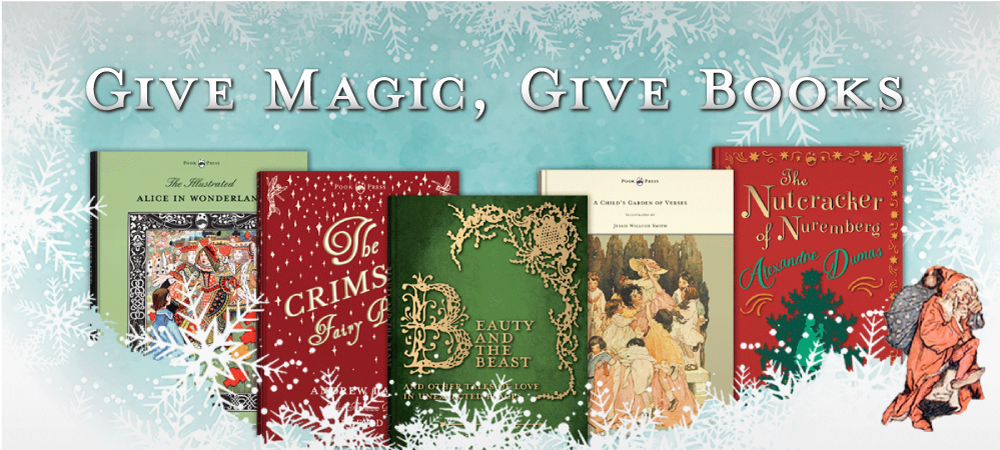

Other Pook Press books you might like:

More from the Blog: