The History of Snow White

The story of Snow White is one of the best known and most loved fairy tales. Its history is an intriguing one, however, with very little known about its exact origins.

The story of Snow White is one of the best known and most loved fairy tales. Its history is an intriguing one however, with very little known about its exact origins. The basic narrative involves a young and beautiful woman, who incurs the jealousy of another (whether that be her mother, step-mother, aunt or competing-wife), and as a result is tricked into a state of suspended animation. The young girl is then locked away for her own protection. The story generally ends with the girl rescued and awoken (usually marrying the Prince or the King), and the ‘other woman’ suffering a less fortunate fate.

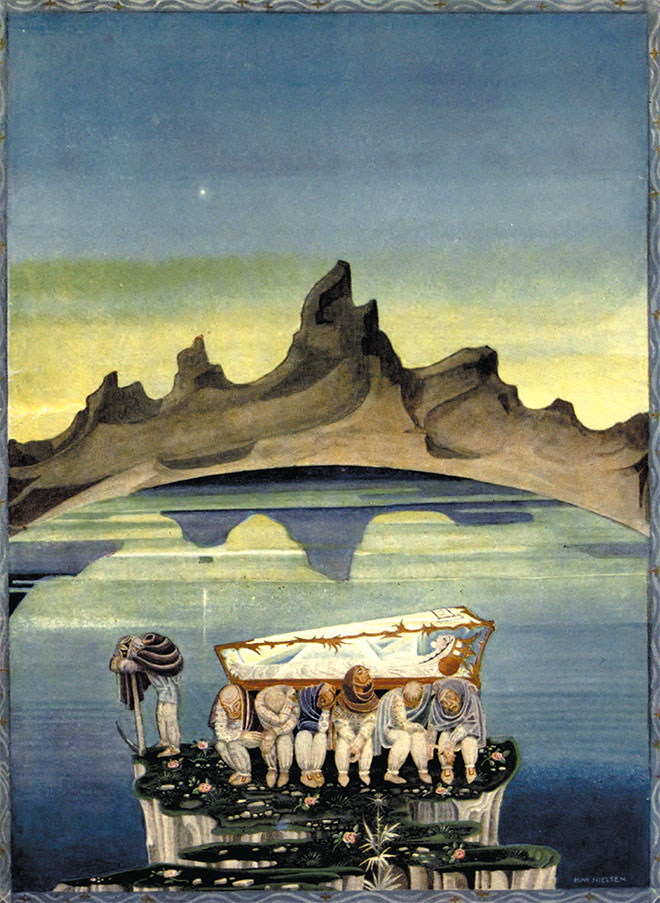

This narrative structure first appeared in print (like so many other folkloric tales) in Giambattista Basile’s Pentamerone (1634-6). Basile was an Italian aristocrat and poet, who had an immense respect for the stories of his homeland. His account of The Young Slave demonstrates many of the literary tropes which have since become standard in Snow White-type stories. It starts with a beautiful young girl named Lisa, who is cursed by a fairy to die when she is seven years old, due to her mother leaving a comb in her hair. When this happens, her mother places her in seven crystal coffins (the Grimm’s later tale has the young woman placed in a glass coffin – with seven dwarfs), and locks her in a room. In this narrative, it is the girl’s aunt who discovers the room, and jealous of her beauty, pulls her hair, which knocks out the enchanted comb. (Again, this comb motif appears in later tales). The heroine is then mistreated made to act as a slave, until she is rescued by her uncle, and married to an appropriate suitor. The idea of a child, cursed to sleep in a near-death-like state, and subsequently shut in isolation for their own protection is incredibly old, but ‘Snow White’ – and of course, ‘Sleeping Beauty’ are the only tales to utilize this trope directly.

SELECTED BOOKS

Snow White – And other Examples of Jealousy Unrewarded

Snow White – And other Examples of Jealousy Unrewarded

Snow White – And other Examples of Jealousy Unrewarded

Snow White – And other Examples of Jealousy UnrewardedAs a testament to the Snow White stories popularity and wide geographic reach – the next incarnation of the narrative comes from Indonesia. This time, it is not a prose piece, but a poem believed to have been written around 1750. It is known in the Malay world as Syair Bidasari and tells the story of a rich merchant’s stunning daughter, who incurred the wrath of the King’s wife. Like Basile’s The Young Slave, Bidasari is ill-treated by the jealous queen, before being placed in a death-like state – this time, by the removal of her enchanted goldfish. The young girl’s beauty is unparalleled, described as ‘a princess fairer than the day; More like an angel than a mortal maid.’

In a fascinating insight into eighteenth century Indonesian concepts of beauty, her cheeks are described as like ‘the bill of a flying bird’, her nose ‘like a jasmine bud’, her pretty face like ‘the yellow of an egg’, and her teeth like ‘a bright pomegranate.’ This version of Snow White is also the first tale where the Queen character starts the narrative by asking if there is anyone fairer in the land. The Queen’s servants (the dyangs) are reminiscent of the huntsman who takes pity on the young woman, and her isolated palace in the desert is a significant forbear to the house in the woods. Like the poisoned apple being dislodged (or the comb being removed, or the ‘stab’ being taken out of her finger in the Celtic variant), Bidasari is only awakened when the goldfish is returned.

Despite these two early precedents, it has also been argued that Snow White could have been based on a real person. One such possibility is Margarete von Waldeck, who lived in the mid-1500s in a small mining town in north-western Germany. After experiencing troubles with her husband’s new wife (so the legend goes), Margarete moved to Brussels, where her beauty attracted the attention of Philip II of Spain. This potential union was deemed unsuitable, and rumour has it that someone poisoned Margarete (her handwriting was shaky enough in her will to suggest tremors due to poison), and she died at the age of twenty-one. There was no happy ending, and no hero-prince for this real life Snow White.

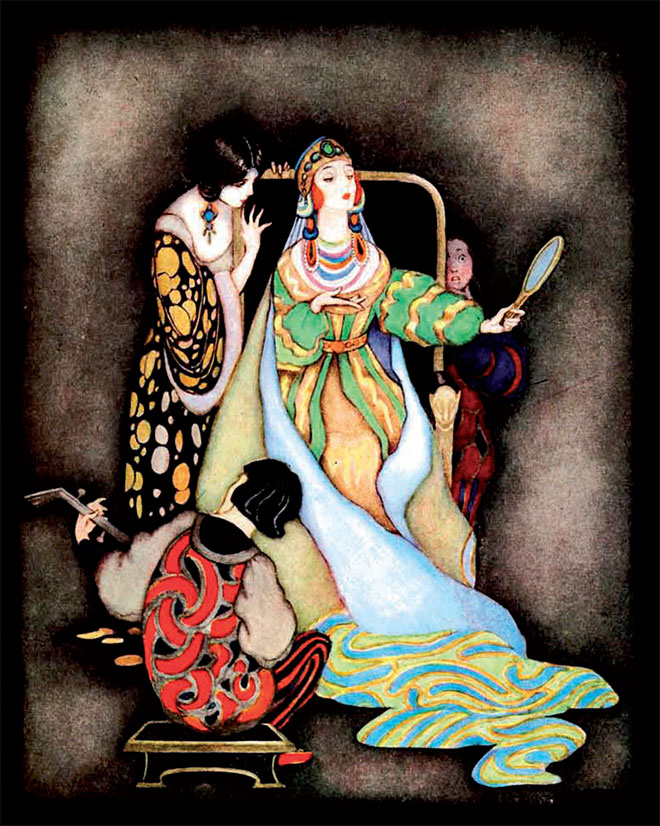

There is also another historical likelihood – the kind and beautiful ‘Maria Sophia Margaretha Catharina von Erthal’. She was born in 1729, so too late for the story of The Young Slave and Bidasari, but quite possibly an inspiration to the Brothers Grimm (who published Schneewittchen in 1812). Historians tell us that Maria’s stepmother (Claudia Elizabeth von Erthal) was a domineering woman who clearly favoured her own children, making Maria Sophia’s life a misery. Their home, a castle in the heavily forested Lohr region, was also very close to the glass-making industries of the region. Lohr mirrors were famed for their extraordinary quality, with the glass being of such excellence that people said the mirrors ‘always spoke the truth.’

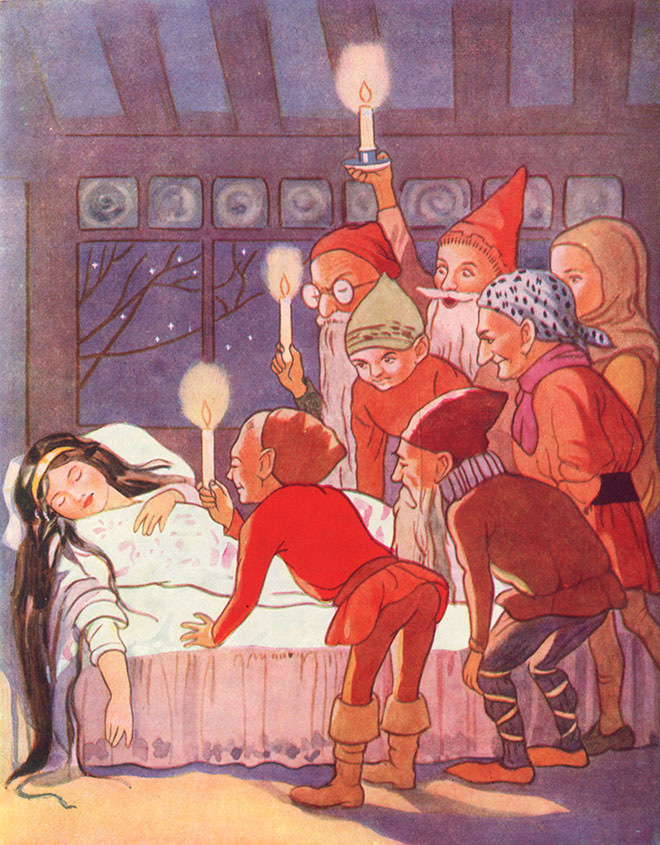

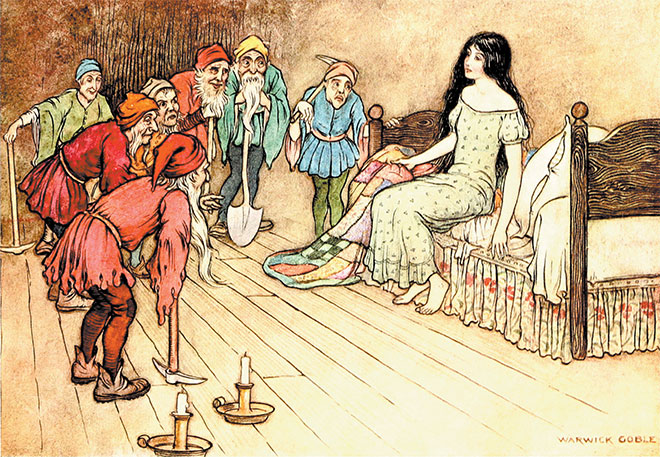

Maria’s father (Prince Philip), gifted his new-wife one of these looking-glass mirrors, and this very object – quite possibly the inspiration for the Grimms’ talking mirror, still survives at the von Erthal castle, which is now a museum. As already noted, the Grimm’s Kinder und Hausmärchen was first published in 1812, and it was the first Snow White tale to incorporate the ‘seven dwarfs.’ These much loved characters could again have been inspired by the Lohr region, which has seven mountains; most of which were mined. In the mid-eighteenth century, mine tunnels were usually very narrow, so only the smallest of miners (or children) could move around in them. The word the Grimms employ; ‘männlein’, directly translates as ‘little men.’

But whilst the ‘real life’ Snow Whites had no fairy-tale ending, Schneewittchen is suitably recompensed for her mistreatment. The Grimms’ tales often include violent endings (unexpectedly gruesome for many modern readers), and the evil step-mother is forced to wear some red-hot iron shoes – in which she must dance until she drops down dead. The Queen also requests to have Schneewittchen’s lungs and liver (as proof of her death), which may be a reference to old Slavic mythology, which includes tales of witches eating human hearts.

It was the Grimms’ version of the story that ‘fixed’ the narrative as we know it today, but many other variants existed across Europe. There is the tale of Myrsina from Greece, where the sun declares three times that the youngest of three sisters is the most beautiful (inspiring her sibling’s jealousy), the story of Nourie Hadig from Armenia, where the mother asks the Moon, ‘Who is the most beautiful in the world’, and the Indian epic poem Padmavati (1540), where the Queen also asks ‘Who is more beautiful, I or Padmavati?’ – in this version, she demands the answer from a truth-telling parrot. In the Portuguese narrative (in a similar manner to the German), the Queen requests the young girl’s tongue as proof of her death. Analogously to the Huntsman’s deception (involving a boar), the servant brings back the tongue of a dog. In a version from Albania, collected by Johann Georg von Hahn (1811 – 1869), the main character lives with forty dragons. Her sleep is caused by a ring, but contains an unusual twist in that a teacher urges the heroine to kill her evil stepmother so that she would take her place.

One particularly intriguing account, is the Celtic story (collected by Joseph Jacobs in 1892) of Gold Tree and Silver Tree, where the truth-teller is not a mirror, a parrot, the sun or the moon – but a trout. Unlike all the other narratives, the ‘competing wife’ in this tale is not jealous of the young girl’s beauty (it is her mother, the vain and capricious ‘Silver Tree’ that plots her downfall) and actually helps ‘Gold Tree’ escape from her murderous parent. In the Grimm’s original version, the step-mother was intended to be the girl’s mother, but they pared this aspect down, to make it more suitable for younger readers.

In the Celtic variant, the mother manages to strike Gold Tree with a ‘poisoned stab’, bearing significant resemblance to the thirteenth century Saga of the Völsungs. This ancient Icelandic prose narrative tells the story of Brynhild, the beautiful and wise daughter of a famous king, who is punished with eternal slumber after an angered Odin (the ruler of Asgard) struck her with a sleeping thorn. The similarity of these three tales, all from a Northern-European geographic base, is particularly telling in terms of the fairy tale’s spread.

As a testament to this story’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, Snow White continues to influence popular culture internationally, lending plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. The tale has been translated into almost every language across the globe, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.