The History of Sleeping Beauty

The tale of Sleeping Beauty is one of the classics of the fairy-tale genre, with a truly fascinating history. Alongside stories such as Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood, it is one of the best-known narratives in the western-European tradition but arguably originates from much further afield.

The tale of Sleeping Beauty is one of the classics of the fairy-tale genre, with a truly fascinating history. Alongside stories such as Cinderella and Little Red Riding Hood, it is one of the best-known narratives in the western-European tradition but arguably originates from much further afield. The story essentially revolves around a beautiful princess, an enchantment of sleep and a handsome prince. But as a result of many adaptations, appropriations and re-tellings, Sleeping Beauty has, over time, undertaken a considerable transformation.

It is one of the best known fairy tale narratives in the western-European tradition

The idea of a child, cursed at birth and subsequently shut in isolation for their own protection is incredibly old, but there are few tales which utilize this trope directly. The first widely known example is connected with the Ancient Egyptian belief in the Fates (or Hathors), who attend the bedside of an Egyptian Queen and predicted the fortunes of her newly born child. In the tale of The Doomed Prince, the child is a boy, and his fate is not threatened by spindles or flax, but ‘his death is to be by the crocodile, or by the serpent or by the dog.’ Similarly to later Sleeping Beauty narratives though, the king builds a great royal house in the desert, in order to protect his newly born child. The ending of this tale, copied from the Great Harris Papyrus (at forty-one metres, the longest known papyrus from ancient Egypt, with some 1,500 lines of text) is unfortunately unknown. It thus forms one of the great folkloric mysteries, of how exactly The Doomed Prince may, or may not, escape his fate.

The first widely known example is connected with the Ancient Egyptian belief in the Fates

SELECTED BOOKS

Other early influences could have come from the story of the sleeping Brynhild in the Saga of the Völsungs (a thirteenth-century Icelandic prose narrative). Here, Sigurd is instructed to ‘ride to Hundarfell, where the fair Brynhild lies asleep.’ Brynhild was the daughter of a famous king, herself famous for her beauty and wisdom, but was punished with eternal slumber after an angered Odin (the ruler of Asgard) struck her with a sleeping thorn. This is perhaps more similar to the ‘Sleeping Beauty’ storyline as we know it than the Egyptian legend; although both are equally intriguing.

The first version to have a truly substantial narrative similarity is a fourteenth-century tale though, the rendition of L’histoire de Troylus et de la belle Zellandine, penned in French by an anonymous author. This appeared in the prose romance Perceforest, which, although written in French, was composed in the Low Countries between 1330 and 1344. An Episode contained in ‘Book III, Chapter iii’, depicts the prince Troylus coming across the sleeping Zellandine, raping her, and Zelladine subsequently giving birth without waking.

This medieval narrative, a shocking forebear for many modern readers, has striking parallels with the first full-length Sleeping Beauty tale, that of the Italian Giambattista Basile; Sole, Luna, e Talia, published in 1634. Basile’s telling is also the most likely influence on Charles Perrault’s La Belle au Bois Dormant (1697) which fixed the narrative as we know it today.

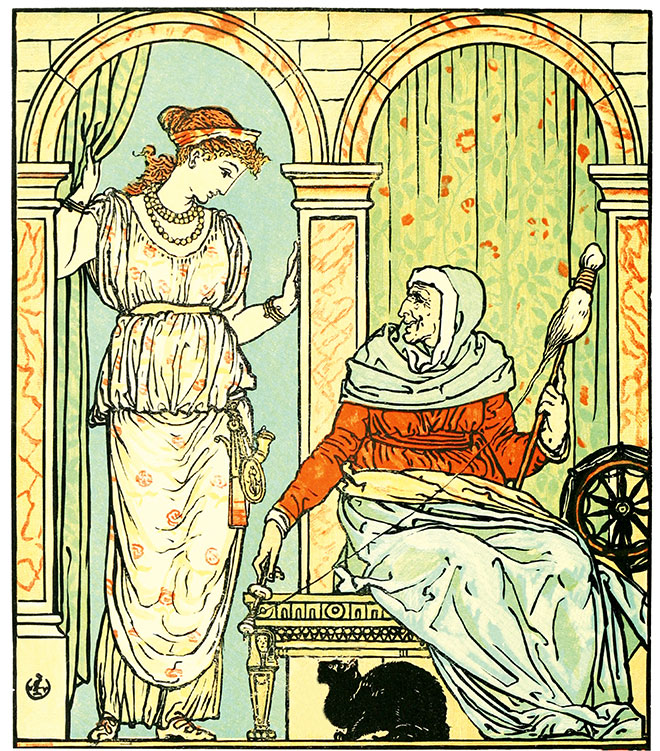

In the early Italian version, the first part of the story corresponds with the earlier narratives of Troylus et de la belle Zellandine and Sigurd and Brynhild – but the second half takes the story into new territory. The first part tells of the birth of Princess Talia, and the soothsayers warning of ‘a great peril awaiting her from a piece of stalk in some flax’ (similar to Odin’s sleeping thorn, and the Hathor’s prophecy). Despite the King’s best efforts to keep her isolated and safe, Talia meets this misfortune, and falls into an enchanted sleep. After being found and ‘admired’ by a travelling King, Talia is later stumbled upon by two young children (analogously representing the childbirth of Zellandine), one of whom wakes the princess by sucking out the flax. The second part then goes on to recount how the King’s step-mother, becoming jealous, attempts to cook and serve the two children (named sun and moon) to the King, and throw Talia on the fire. The plan is foiled though, and the step-mother is suitably punished.

Charles Perrault’s ‘La Belle au Bois Dormant’ fixed the narrative as we know it today

Perrault’s tale follows the same narrative pattern, and he even goes so far as to call the two children L’Aurore (Dawn) and Le Jour (Day) in a nod to Basile’s story. In the second half of this variant, the step-mother is actually an ogre, and the Prince and the Princess had got married in secret. Some scholars believe that these two halves were originally entirely separate tales, and consequently, the Brothers Grimm – ever the consummate folklorists, decided to represent this separation in their collection.

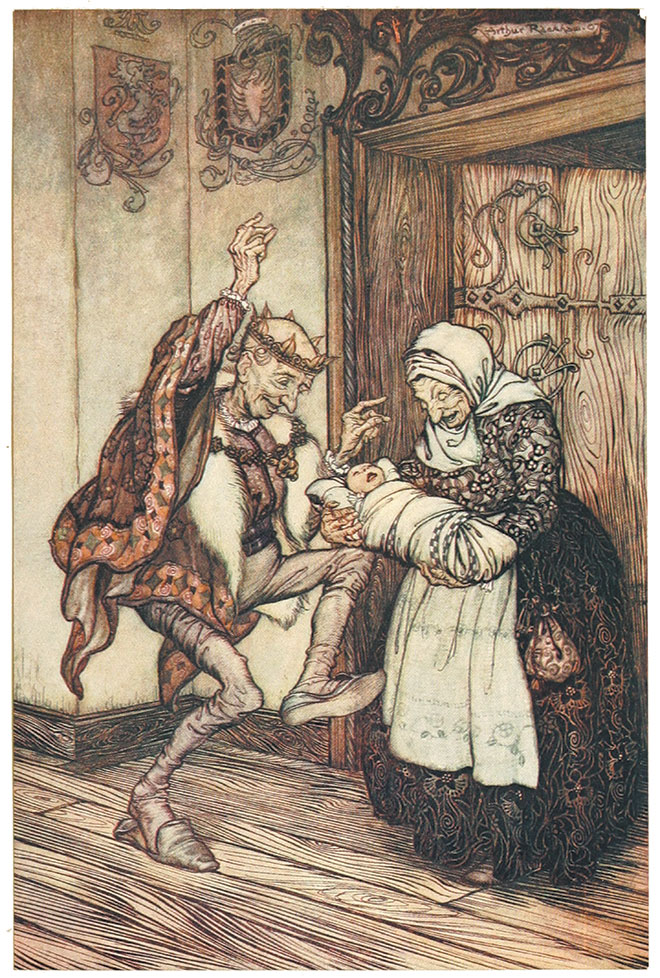

Their tale of Little Briar Rose (1812), who falls into the enchanted sleep after a prick from a spindle, ends (like the original tellings) when the prince arrives to wake the sleeping beauty. Unusually for the Brothers Grimm, their story is one of the tamest of the ‘sleeping beauty’ narratives, with none of the attempted cannibalism, adultery or rape found in earlier renditions. The Brothers considered rejecting the story on the grounds that it was derived from Perrault’s version, but the presence of Brynhild in the Norse sagas convinced them to include it as an authentically German tale.

The incident of the sleep-thorn (the prick from the spindle) is also found in a Southern Indian tale, that of Little Surya Bai. This formed part of Mary Frere’s Old Deccan Days (1868), a collection of stories taken from oral traditions in Southern India. In this version, it is a splinter coming out of the wall of an Eagle’s cage, that causes the young girl to fall down senseless – before being rescued and married by a Rajah. Here, the story’s ‘second half is included, and the ‘sleeping beauty’ becomes the victim of jealously not by her mother-in-law, but of another wife. Like Basile and Perrault’s narratives, the wicked first wife is eventually punished, and Surya Bai and the Rajah live happily for the rest of their days.

As a testament to this tale’s ability to inspire and entertain generations of readers, the story of The Sleeping Beauty continues to influence popular culture internationally. With a massive geographical range, it lends plot elements, allusions and tropes to a wide variety of artistic mediums. It has been translated into almost every language, and very excitingly, is continuing to evolve in the present day.

SELECTED BOOKS

La Belle Au Bois Dormant – Avec Illustrations Par Arthur Rackham

La Belle Au Bois Dormant – Avec Illustrations Par Arthur Rackham

La Belle Au Bois Dormant – Avec Illustrations Par Arthur Rackham

La Belle Au Bois Dormant – Avec Illustrations Par Arthur Rackham